Last weekend's winter storm caused only moderate flooding on New Hampshire's Seacoast. But it provided a window into how rising seas will make flooding more frequent, bringing challenges to the state's coastal communities.

The full moon in the wake of the nor’easter brought astronomical high tides, also known as king tides, of at least 9 or 10 feet in towns like Hampton. It’s one of the most at-risk towns in the region from the rising seas driven by climate change.

A flyover of the coastline during Wednesday’s king tide showed those risks in stark contrast.

The flight was organized by local environmental groups, including the Conservation Law Foundation and Piscataqua River Estuaries Partnership, and the aviation nonprofit LightHawk.

One passenger was Hampton conservation commission chair Jay Diener. He says this year, his town is expecting 55 tides above 10 feet – the level at which flooding becomes very likely in some parts of town. He says they’re seeing more of those high tides with each passing year.

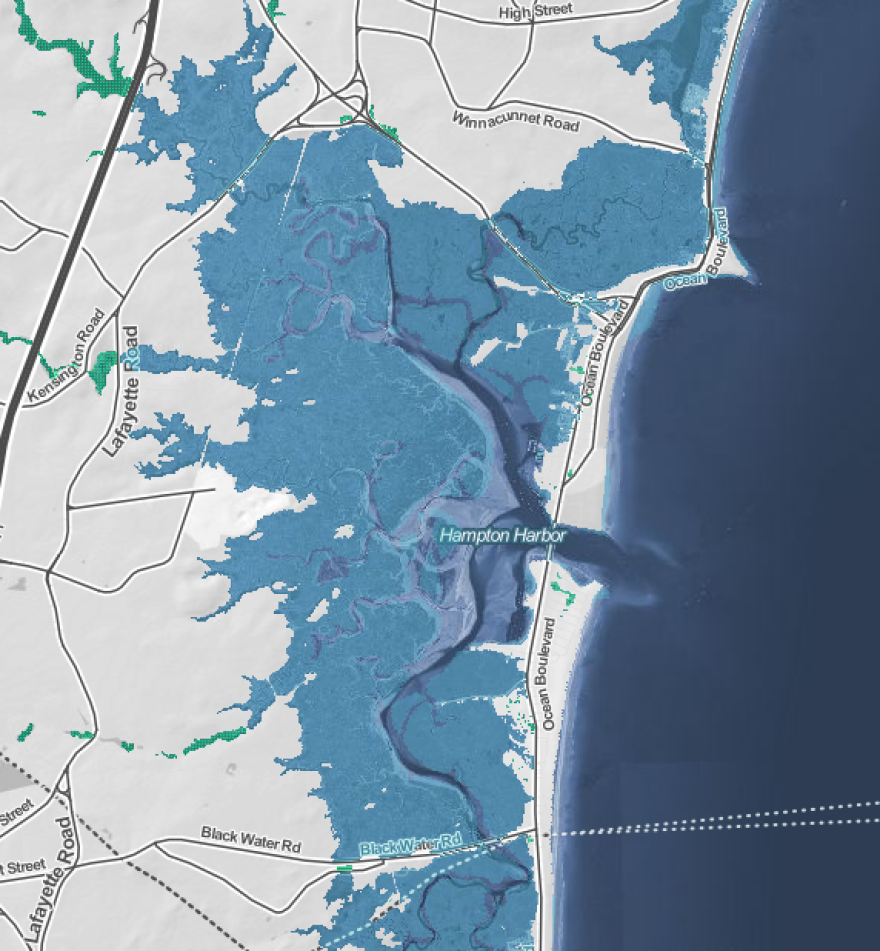

According to data mapped by the nonprofit Climate Central, the Seacoast is already at high risk.

This data says even with moderate reductions in global carbon emissions, the seas around Portsmouth will rise two feet by 2080.

This would put parts of the coast underwater – including the outer edge of Rye and larger swaths of Hampton and Seabrook, especially between Route 1 and Route 1A along the tidal Hampton and Blackwater Rivers.

These projections can seem distant or unimaginable. But in some Seacoast towns, they’re already visible.

Increasingly high tides, more frequent low-level flooding and storms that erode away the shoreline are daily manifestations of sea level rise.

Our flight set off from Pease International Tradeport just before Wednesday’s high tide of 9.9 feet.

The small propeller plane passed first over Portsmouth and the tidal Piscataqua River, abutting the city’s Schiller Station power plant, Sprague oil storage tanks, historic homes and landmarks, and heavily trafficked, low-lying bridges and roads – including I-95 and Routes 1, 4 and 16.

These assets are increasingly vulnerable to tidal and storm-related flooding, subsidence and saltwater intrusion from rising groundwater.

Pollution has degraded the surrounding estuary, including Great Bay and Little Bay, making it less able to absorb storm surge and protect surrounding homes from flooding. During our flight, ice and snow flowed seamlessly from roadways and people’s yards out onto the water itself.

To the south, the coastal Route 1A split off along the ocean and became separated from the mainland by a stretch of grassy marsh that’s usually exposed. On Wednesday, it was completely inundated by the high tide, leaving a layer of greenish seawater over frozen white.

The marsh forms a backyard to the oceanfront homes along 1A, which is frequently splashed, flooded and even damaged by storm surge and high waves. From above, they appeared isolated and vulnerable, a thin line through icy water.

“These homes are pretty well protected from that sea wall on the ocean side, but I don't know how much protection they have on the back side,” said Jay Diener on the plane’s intercom as we flew over.

Flood insurance is getting more and more expensive for the area’s most at-risk homes, he said. Some homeowners are willing and able to keep paying it. For others who may want to leave, the flood risk and costs are making it harder to invest in and sell their properties.

A recent study showed that’s also depressing Seacoast property values, which supply towns with vital tax revenue.

Further down the coast, near Hampton, large homes with elegant landscaping faced the rocky seawall. Its top half was covered in snow, the lower half washed clean by the high tide.

Diener pointed out state beaches and parking lots, which he said are frequently flooded and damaged by storms. Then the seawall gave way to flat sand, and the frozen, flooded marsh opened up again behind Hampton and Hampton Beach.

He noted two streets that poke out into the marsh on small spits, which he said are now sometimes inaccessible during high tides and storms.

The plane circled over the marsh behind Hampton, where Diener pointed out the homes that are most often flooded by high tides and rainfall. Whole neighborhoods appeared to sit directly on the ice floes crowded up against the ends of their streets.

South of Hampton, the beachfront corridor in Seabrook is also vulnerable. Diener says the two towns are collaborating on their planning efforts – but it’s an uphill climb.

“Not knowing how much funding we need or where we would go to get it is one of the biggest obstacles that we’re dealing with,” he says.

Diener says climate change is pushing towns like Hampton, ready or not, into uncharted territory. He says it can be difficult to know where or how to begin planning adaptations and response.

“Nobody really knows what the answers are,” he says. “Nobody really understands what all the options are that we have available to us and how to get to that point.”

Hampton hopes to begin adapting in one clear way this spring. They’ll vote at town meeting this March on whether to require new development and construction in the wetlands district to be built on pilings.

Diener says some homeowners are already elevating their homes to avoid flood damage.

Aerial support for this story was provided by LightHawk. This story has been updated to correct a caption in an earlier version, which misidentified Memorial Bridge in Portsmouth as the I-95 bridge.