The Coakley Landfill on New Hampshire’s Seacoast is back in the headlines, more than 30 years after it became a Superfund site.

Neighbors are again worried the site could be poisoning their drinking water, after a rash of childhood cancer cases nearby and the discovery of dangerously high levels of PFAS chemicals at the landfill.

That’s despite local officials' promises that the landfill is safe, under control and not a threat to nearby residents. In fact, they say the landfill is mostly just misunderstood.

Humble beginnings

On the rusty, chain-link gates of the landfill, a crooked yellow sign warns: “Hazardous substances may be present, keep out.”

Beyond that, a rough gravel road leads toward the landfill, which, from here, just looks like a huge grassy hill. And strolling toward it in shirtsleeves and sunglasses is Portsmouth city attorney Bob Sullivan.

He can remember when Coakley wasn’t so bucolic. In fact, he’s one of the few people who’ve been part of this story since it began.

“It started out as a quarry which had been exhausted of materials, so that it was a big hole in the ground – a really big hole in the ground,” Sullivan says.

For years, this really big hole sat carved out of bare bedrock. Landfills in the 1970s weren’t lined underneath, or covered above. Coakley collected household, industrial and municipal waste from nearby towns including Portsmouth, from factories and the old Pease Air Force Base.

“And that was actually kind of state of the art back in the 1970s, when people looking to get rid of municipal waste – trash – they would find a hole in the ground somewhere and fill it up,” Sullivan says. “Probably seemed like a good idea.”

But lots of contaminants – including dioxins, mercury and arsenic – were leaching out of the landfill through groundwater, and in the early 1980s, they started turning up in people’s wells.

The state shut down the landfill in 1985, and a year later, it became one of the nation’s first Superfund sites – a federally managed toxic waste cleanup area.

Now, it's covered in thick, dry grass, studded with metal and plastic pipes poking out of the ground. Some vent gas to keep the landfill from exploding. Others go all the way down to the groundwater, to monitor the contamination.

A standard remedy

This whole system is part of the remedy the Environmental Protection Agency chose for Coakley in the 1990s.

It involved a standard procedure – piling the waste up and covering it with the thick, impermeable cap that forms the grassy hill we’re standing on. The next part of the plan called for long-term monitoring, while expecting the toxins to fade away on their own.

Also standard at a Superfund with multiple contributors was the group formed by the towns and businesses responsible for the pollution: the Coakley Landfill Group. They’d be in charge of paying for and carrying out the cleanup, per the EPA’s instructions.

Once the cap was finished in the late 1990s, this once-chaotic Superfund site went quiet.

Most neighbors were connected to public water, and over time, they stopped talking about Coakley. New families moved in who didn’t even know the landfill was there.

Bob Sullivan says testing shows contamination has declined steadily inside the landfill – just like they planned. These days, he thinks Coakley might be a nice place to sunbathe or sled.

“When this grass grows a little bit, it’ll look like maybe the foothills in Wyoming,” he says.

To Sullivan, Coakley is a model Superfund – a safe, secure, success story.

But in 2016, all of that came into question when PFAS contamination turned up at Coakley as part of routine tests.

‘Please help us’

PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, is a class of industrial chemicals that was common in American manufacturing for decades, up until the early 2000s.

It’s found in Teflon, Gore-tex, food wrappers and firefighting foams. It doesn’t biodegrade, and it’s been linked to liver and kidney diseases, developmental and immune system problems, high cholesterol, pregnancy issues, and cancers – including testicular, kidney, breast and prostate.

(Scroll down for an infographic about where PFAS comes from, its health effects and regulation.)

The chemicals were found at high levels in surface waters along the edges of the landfill. Their discovery came just as PFAS began to make headlines in New Hampshire and nationwide.

The EPA had put out an advisory limit on the chemicals, which soon became law in New Hampshire.

Also that spring, the state had found a cluster of cancer cases on the Seacoast. Now, neighbors worried Coakley – and PFAS – were to blame.

“Please help us gain control of this situation,” begged neighbor Amy Miller through tears at the Portsmouth city council lectern, just before Christmas in 2016.

She and others in Greenland who were still using private wells near the landfill had come to the city council to ask for public water hookups.

“I honestly wonder how Peter Britz and Attorney Sullivan sleep at night. Have they no conscience?” said another resident, Janet Tibbets, while the council timekeeper – Bob Sullivan – tried in vain to cut her off. “I think it is time for the responsible parties to start to live up to that name, and provide public water to Breakfast Hill in its entirety."

Portsmouth is still studying whether those public water hookups near Coakley are feasible.

‘What the heck is Coakley?’

Another Greenland resident at that meeting in 2016 was Jillian Lane. She lives in a big, airy house, tucked away on a tree-lined cul-de-sac.

It’s peaceful outside – but through the front door, mild chaos reigns. Lane juggles hairbrushes, dolls and her morning coffee as she and her husband wrangle their three daughters – aged 3 to 9 – before summer camp.

The Lanes built this dream home less than 10 years ago. It was a place to feel safe doing everyday things, like rinsing an apple at the kitchen tap – which Lane’s middle daughter Abby is doing this morning.

Lane never thought she’d have to worry about their private well. Then, in 2016, she started to hear about kids in the next town over getting rare forms of cancer.

Some kids died. Others are still undergoing treatment.

There were only about a dozen cases, but it was enough to count as an official double cancer cluster. And Lane was desperate to know whether her kids were at risk. So she started reading more.

“Underneath one of the articles was just a comment from a public citizen that said, 'Coakley?'” she says. “And I was like, ‘Coakley, what the heck is Coakley?’ So I started Googling it.”

What she found was a landfill-turned-toxic waste cleanup site just on the other side of the woods in her backyard.

‘Everything’s under control’

Lane was horrified as she read old EPA and state Department of Environmental Services reports about the poisoned wells around Coakley in the 1980s. She'd had no idea it was so close – state law doesn't require such disclosures.

But when Lane called Greenland’s town administrator, she was told not to worry.

"She was very, very reassuring, and her perspective was that ‘It's under control, EPA is involved, New Hampshire DES is involved, we have boxes and boxes and boxes and files upon files and everything's under control,’” Lane says. “And I believe that that's how the town felt, based on everything that they'd been told and had been shared with them."

But the town was about to learn something new about Coakley, with the discovery of those high levels of PFAS in surface water monitoring.

It was only the latest place the chemicals had turned up in New Hampshire. At that point, amid PFAS contamination around the Saint Gobain factory in Merrimack and ongoing remediation at Pease International Tradeport, the chemicals were making near-daily headlines.

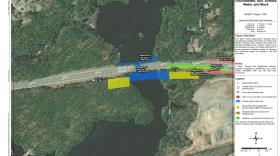

See select PFAS sampling results and other points of interest below, and click here to explore state data.

Public officials told Lane and her neighbors there was no proof the pediatric cancer cases in Rye were tied to Coakley. But the neighbors were not reassured.

Lane says she was filled with anxiety for her daughters, who'd grown up with their private well in Greenland. They’d even built the house with a humidifying heating system.

"We're drinking the water, and we're bathing in it, brushing our teeth in it,” Lane says. “And we had no idea we were living with this potential problem."

Lane started going to meetings -- sparring with EPA workers and Portsmouth city officials, demanding answers to her questions, pushing for more studies and public water lines to her neighborhood.

And then, in early 2017, PFAS was found again -- even closer to home. It was in Berry's Brook, which trickles from Coakley out into the surrounding neighborhood.

Reading the numbers

Lane wasn't taking any chances. She was having her well tested, and making some big changes at home.

After a lot of debate, she and her husband decided to spend several thousand dollars on high-tech PFAS water filters – granular activated carbon for the whole house, and reverse osmosis for their drinking water.

That filter covers a kitchen tap and the ice-maker in their freezer.

“For me, it was knowing the potential of it coming,” she says. “I didn't want my kids to be exposed to it whatsoever. I want to remove it."

All that time, the Coakley Landfill Group was testing private wells in Lane's neighborhood -- and they weren't reporting finding any PFAS. Then, last fall, that changed.

“I came back with three parts per trillion,” Lane says.

To her, it was a sign the toxic chemicals were creeping toward her home.

But it turned out regulators weren't telling her the whole story. At first, the test results didn't include very low levels of PFAS -- ones the EPA couldn't be confident were accurate. But that changed last fall. The EPA decided to start reporting all the data, high or low.

That's when Lane saw her first PFAS detection -- but officials' efforts to explain the change still left her and other neighbors confused and worried. It wasn’t clear to them just how long these low levels of PFAS might have been in their wells.

This was an example of a miscommunication that fueled the panic at Coakley.

Even so, three parts per trillion is a tiny amount -- imagine three grains of sand in an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Federal and state standards say water with 70 parts per trillion PFAS is safe to drink.

But those standards are beginning to be challenged at the federal level.

‘Not a bright line’

This June, the Centers for Disease Control put out a 800-page toxicology profile of PFAS. The EPA, under former administrator Scott Pruitt, had reportedly sought to keep the study private.

The new data said as little as 7 to 11 parts per trillion of some kinds of PFAS could threaten human health. That's far less than EPA and state thresholds -- and a lot closer to levels found near places like Coakley.

In late June, at the EPA’s first big regional public meeting on new PFAS regulations in Exeter, the report was the elephant in the room just days after being published.

(Read the CDC's 2018 PFAS toxicology profile. Public comment is open until Aug. 20, 2018.)

On the stage of a high school auditorium, in front of about 200 other residents and regulators, acting CDC toxicology director Bill Cibulas made an unscheduled appearance to clarify his agency’s new findings.

"This is not a bright line here – these are not regulatory actions, they're not necessarily thresholds,” Cibulas said. “We're not saying that exposures estimated above our minimal risk levels are to be associated with health effects.”

Instead, he says the CDC uses those low risk levels as a public health tool -- to identify places where they should look more closely for potential problems.

Jillian Lane, her neighbors and residents from across New England were also at that meeting.

There were families from Massachusetts:

"I catch myself wondering whether my dad's cancer, my grandmother's thyroid disease and a combination of diseases that has left my uncle dead was in part due to the exposure of PFAS and other co-contaminants,” said a man from the city of Westfield, MA, holding back tears.

And activists from near Pease Tradeport:

"Never did it cross my mind that I had to question the quality of the water that my children were drinking, and so I just want you to understand that I live with guilt every single day,” said Andrea Amico, co-founder of Testing for Pease.

Since that the meeting, their pleas for more government response are starting to see results -- both state and federal officials are pledging new regulations and testing programs.

At Coakley, the EPA and Landfill Group are working on studying bedrock beneath the site, and fish and wetlands around it, hoping to learn more about the spread and source of the contamination.

They announced possible new leads on that just this week.

Waiting on proof

Much of this action has been spurred by public outcry. But Jillian Lane says part of her still wishes she’d never Googled Coakley in the first place.

It’s hard, now, to trust the government to manage the situation, after years of closed-door meetings, and delayed data, and regulators who made her feel ignored.

“The public shouldn't have to be driving this process,” she says. “The public shouldn't have to be forcing the responsible party to be doing what's right and what's in the best interest of the public and protecting public health. You know, none of that contributed to building trust with the public.”

Bob Sullivan, the Portsmouth city attorney and Coakley Landfill Group leader, disagrees. He says the public should trust the process and reassurances at Coakley.

He reiterates that all the testing they’ve done shows the PFAS levels in people's wells are safe under current EPA standards. And he says what PFAS is there could be coming from other sources – it can’t be tied definitively to Coakley.

Sullivan thinks politicians and the media are stirring up this controversy for personal gain.

“I don’t have a problem at all with people caring about Coakley, I think they should,” he says. “But caring about it doesn’t necessarily mean being upset about it.”

Asked if there’s anything he’d have done differently at the start, as Portsmouth’s city attorney, if he’d known Coakley’s PFAS problem was coming.

“Yeah, I think I’d have quit my job and gone into private practice,” he says, laughing.

What’s so aggravating about how the controversy has unfolded?

“We’ve done a really good job out here, complying with all the instructions we got from the Environmental Protection Agency,” Sullivan says. “We’ve protected the public health and at the same time as much as possible protected the public taxpayer, and yet we’ve been vilified to the Nth degree.”

Vilified, in Sullivan’s view, by people like Jillian Lane – who says she knows her family can't escape all environmental risks anywhere they go.

But just this month, they decided to leave Greenland and move to another town on the Seacoast.

Lane still wants the same things regulators and public officials want -- proof of whether Coakley is truly safe, and answers to the scientific questions that still surround it.

She says she's not abandoning her activism. She just doesn't want to live next to the landfill anymore.

NHPR’s Jason Moon contributed reporting to this story. This story was updated Tuesday to reflect new developments at the landfill.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story incorrectly said Berry’s Brook ran into Jillian Lane’s neighborhood. In fact, it runs to a different neighborhood near the landfill. The audio for part 1 of this story has also been updated to reflect that dioxins were found at Coakley in the 1980s, not dioxanes, and the CDC toxicology profile for PFAS was released in June, not May.