A first-of-its-kind water treatment system has begun filtering high levels of toxic PFAS chemicals from the groundwater at Pease International Tradeport.

It’s the latest, biggest phase of millions of dollars in government response after PFAS was found in a drinking water well at Pease in 2014.

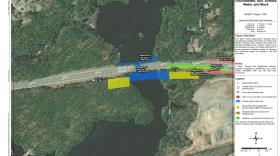

Between the runways and the woods at the former military base-turned-Superfund site, a tangled grid of pipes covers the ground. It connects a series of water wells that are helping slowly clean up not just one person or business’s water supply – but a whole aquifer beneath the ground, which is connected to several private drinking water wells in Newington.

Those residents are currently using filters, but years from now, when this plant’s work is done, their tap water will be clean again.

“And so what we have here, this is what they all look like,” says Rob Singer, a project manager with the government contractor that built this $8-million-dollar water treatment plant.

He’s leading a tour of the facility for a big group of state and federal officials, and he points to a small opening in the pavement, containing a few pipes and gauges.

“This is basically a PVC pipe in the ground like a well like anyone might have,” Singer says. “And we have a pump in there and there’s monitors that monitor the level of the groundwater.”

All these wells and pipes lead into a treatment plant that sits on top of Pease’s former fire training operation – where the Air Force used to use firefighting foams full of PFAS-class chemicals.

PFAS was common until the early 2000s in all kinds of products. It doesn’t biodegrade and has been linked to cancers and other health issues.

And it doesn’t take much PFAS to cause those problems. The CDC says as little as 11 parts per trillion of some of the chemicals may put human health at risk. The EPA’s suggested limit is 70 parts per trillion.

Compare that to levels found at Pease: the well that was shut down for contamination in 2014 contains up to 2,000 parts per trillion PFAS.

And the aquifer beneath this fire training area contains 50,000 parts per trillion.

The Air Force says this treatment facility could be a model for long-term cleanup near other contaminated bases nationwide.

It’ll pump the groundwater out of the aquifer, scrub it of PFAS, and put it back in the ground – over and over for years until the groundwater is safe to drink.

Two more similar facilities are now being installed at Pease. One will clean the aquifer that sparked this whole response, potentially allowing it to be reused many years in the future. The other will serve nearby Portsmouth residents.

“So everyone needs to be careful, the floor might be a little bit slippery,” Rob Singer says as he leads his tour group inside the plant, where cutting-edge science is everywhere.

This facility is the first in the country to filter PFAS with a special regenerative resin. Singer picks up a cup of that resin and gives it a shake. It’s just an unremarkable white, off-white powder.

“So this is the material that’s in all these tanks – just a fine, Styrofoam beads-type material,” he says.

The resin grabs the PFAS as water moves through it. Every now and then, operators can flush out the resin with salt and water – separating out the condensed PFAS waste.

Singer says they’ll fill up at least dozen tall tanks of that PFAS sludge as they treat tens of millions of gallons of water.

The toxic materials are taken away to a special disposal facility and burned. And the water that heads back into the aquifer doesn’t contain any detectable PFAS at all.

And this is just one aquifer that’ll take years to clean up. Senator Jeanne Shaheen was on this tour, and she says she knows the government is still in the early stages of its response to the PFAS problem.

That’s why she says she’s worked to make Pease the center of a national health study on PFAS – and she’s calling for more public health attention to the issue in New Hampshire.

“We’re just really beginning to learn how widespread the impact is and the effect to drinking water, and that’s a huge issue,” Shaheen says.

But PFAS testing and filtration is still prohibitively expensive for most towns and homeowners.

New Hampshire waste management chief Mike Wimsatt says he hopes these special treatment plants going in Pease will help bring those costs down.

“It’s unfortunate that we see these compounds in so many places in the country,” he says. “The only positive of that is you have an awful lot of people working on it, and it’s going to make whatever technologies become available a lot cheaper because… you’re going to recognize those economies of scale.

“It means in the end when someone wants to buy a filter for their home, it’s going to be cheaper,” Wimsatt says.

He hopes that’ll happen as new state standards come in to mandate PFAS monitoring in the next year. That way, more people can find out if and how the problem affects them.