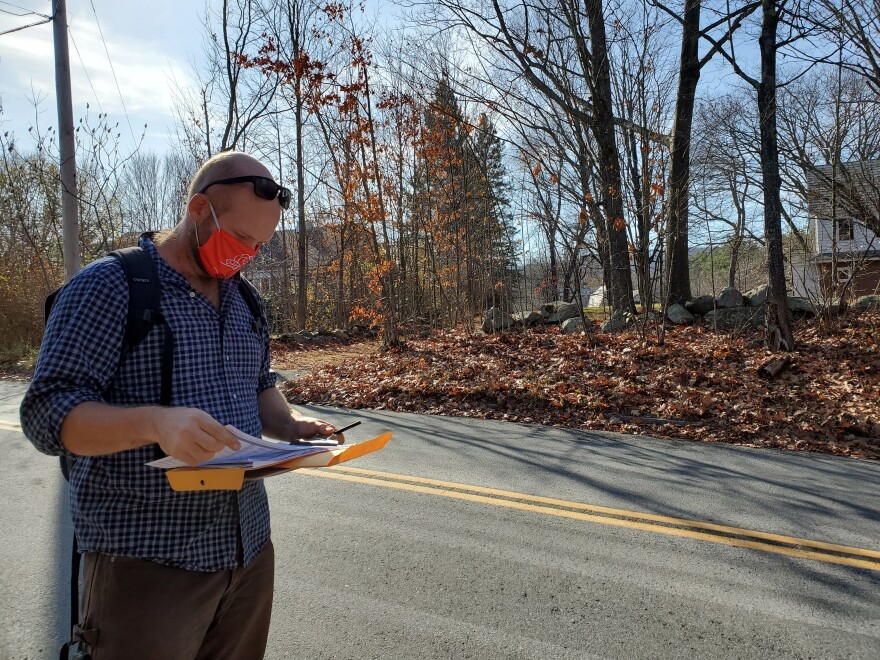

On an unusually warm Saturday morning in November, Rory Gawler and some other organizers were getting ready to knock on doors throughout Lebanon.

“Hopefully people won’t pretend they’re not home,” Gawler said, who’s lived in town for 12 years, as he and other canvassers prepared manila envelopes with brochures, petitions and pre-stamped envelopes.

Since Gawler was out canvassing a few days after the general election, he had a piece of paper on the back of his clipboard that read “Here to talk about a local Lebanon issue.”

Over the past few weeks, Gawler and others have been hitting the streets to make a big ask: cut the Lebanon police budget in half, and direct the money toward social services.

Organizer Sasha Brietzke was one of those making the pitch to neighbors that day.

“Specifically we’re asking for a 50 percent cut in the budget from the Lebanon P.D. to health and human services by 2022,” she said.

Brietzke and Gawler are with the Upper Valley Democratic Socialists of America, working on a new campaign they call Care, Not Cops. Brietzke says it follows on work happening across the country, in places like Minneapolis and Austin.

Lebanon currently spends about 11 times as much on its police department as it does on health and human services. Organizers want $3 million, half of the city’s $6.3 million police budget, reallocated to what they call critical community needs, like health care, housing and food assistance.

But within less than a mile stretch of this neighborhood, no two views on this proposal were the same.

Two people signed on to the group’s petition. Another woman asked for more information. One man called himself an incrementalist, and said he and his wife were unsure about the idea.

Gawler and Brietzke handed him a pamphlet with more details about the proposal.

Other people flat out rejected their proposition, and Brietzke says she understands that.

“I think it makes total sense that people’s knee-jerk reaction is to say, ‘I don’t want to defund the police,’ because we have been trained as citizens of this country to equate police with public safety,” she said.

She says that public safety can look like public health initiatives.

“It can look like community centers. It can look like access to affordable health care,” Brietzke said. “And once we reframe what public safety looks like, people seem to be receptive to that shift, but it does take time.”

The goal of reallocation, Brietzke says, is to address the root of social problems. The way she and the Upper Valley DSA see it, police just respond to the symptoms of those issues.

The group is proposing the $3 million be spent on creating a new department, or position, that would focus on community safety and wellness; increasing financial support of local housing and mental health organizations; and diverting mental health calls away from the police to mental health professionals.

They say these efforts would help prevent people from entering the criminal justice system, and instead would redirect them “toward organizations that can provide the support they need.”

But to get there, changes would need to happen over two years. For the 2021 budget, the group proposes hiring freezes and restrictions on overtime. For 2022, it’s asking for staffing cuts, reducing traffic stops, and restrictions on overtime.

Brietzke and Gawler know this is an uphill battle. As they canvassed, they walked past a sign that said, “Defend, Not Defund.” In fact, there’s a counter petition, with more than 1,200 signatures.

Curt Jacques, a local business owner, started it.

“The consensus at least from what we're seeing, especially from the comments made on this petition, people are comfortable with what we have and support the police 100 percent,” he said.

Jacques says he and many others rely on the police, and that for the department to keep doing its job, it needs more money, not less.

“We just are faced with so many more issues because of the commerce hub that we are,” he said.

During the daytime, Lebanon’s population increases about three to four times, to 30,000 or even 40,000 people, as they come to work and shop from both the Vermont and New Hampshire sides of the Upper Valley.

Lebanon Police Chief Rich Mello says that’s why the community requires a larger police force -- 33 full-time officers -- and, therefore, a larger budget. Previous NHPR reporting found that Lebanon has the fourth highest spending per capita on police in the state.

Mello says he does agree with the activists that social services need more funding.

“There's absolute agreement there. They're right on the money as far as society in general, not just the state of New Hampshire,” he said. “Across the country we need to allocate -- or it would be nice to allocate -- more resources to mental health or substance abuse crises. The question is how to do that.”

Mello thinks that funding should come from the state, not the police or city budget. Cutting 50 percent of his budget, he said, would leave “the community unprotected and unserviced for the things that it needs.”

He says most of the calls his officers respond to are clear policing issues, though many do have a link with mental health problems or substance use.

“For example, maybe we have a shoplifting call, and we get there and we deal with somebody and the reason they’re shoplifting is because they have a substance abuse issue,” he said.

But, Mello says, while there has been a slight uptick in mental health calls during the pandemic, it’s not very often they get a call for just a mental health crisis or substance abuse crisis. For that, he says he is working with West Central Behavioral Health to establish a mobile crisis team staffed by mental health professionals, similar to those in Manchester and Nashua.

Brietzke and Gawler, two of the organizers behind the local Care, Not Cops campaign, support permanent funding for a mobile crisis team with money from the police budget.

But they also want community members to think more broadly and critically about how public safety can be achieved. They say that requires taking a closer look at the city’s police budget, and having a say in how that public money gets spent.

“Hopefully once we talk about, more and more, how the budget is a living document of our values, we can convince people to divert resources from bloated budgets, like the Lebanon PD, towards the issues that impact the community the most, which are mental health services and affordable housing,” she said.

Brietzke and her group will present their proposal at a city council meeting Wednesday.

This, they say, is just the beginning of a conversation they want top of mind in the Upper Valley for years to come.