Last week, the ConVal School District sued the state, claiming that lawmakers are failing to fund an "adequate education" and that local taxpayers are shouldering more than their fair share.

This isn’t the first time New Hampshire has seen an education funding lawsuit. Districts across the state - from Claremont to Pittsfield - made similar arguments in court decades ago. And they won.

But many say the battle is far from over.

At a recent State House hearing before the House Education Committee, John Freeman, the Superintendent of Pittsfield Schools, walked up to the mic with a stack of budget papers.

He gestured towards a series of paintings hanging behind the lawmakers.

“I’d like to compliment your taste in art by having some of our student’s work displayed here,” he said. “And we hope we’re going to be able to afford an art program for our students next year.”

His jab got laughs, but Freeman was serious.

“The state funding formula has strangled us,” he continued.

[Click here to read the full "Adequate" series]

Over the last decade, the district has cut teachers and all AP and foreign language classes. And even with all these cuts, the local tax rate keeps going up.

“The local education tax rate is almost 50 percent higher over the last 10 years with a flat budget,” Freeman said in a recent interview. “That is not right!”

And according to some, it’s not legal either.

That’s because of a series of New Hampshire Supreme Court decisions that govern how the state is supposed to fund education. They’re called the Claremont cases, named after the Claremont school district, which, along with Franklin, Berlin, Pittsfield, and Allenstown, sued the state in the 1990’s.

One of their lawyers was Andru Volinsky, a Democrat from Concord who now serves as an Executive Councilor.

In the early 1990’s, Volinsky took a tour with the team of lawyers helping these schools sue the state.

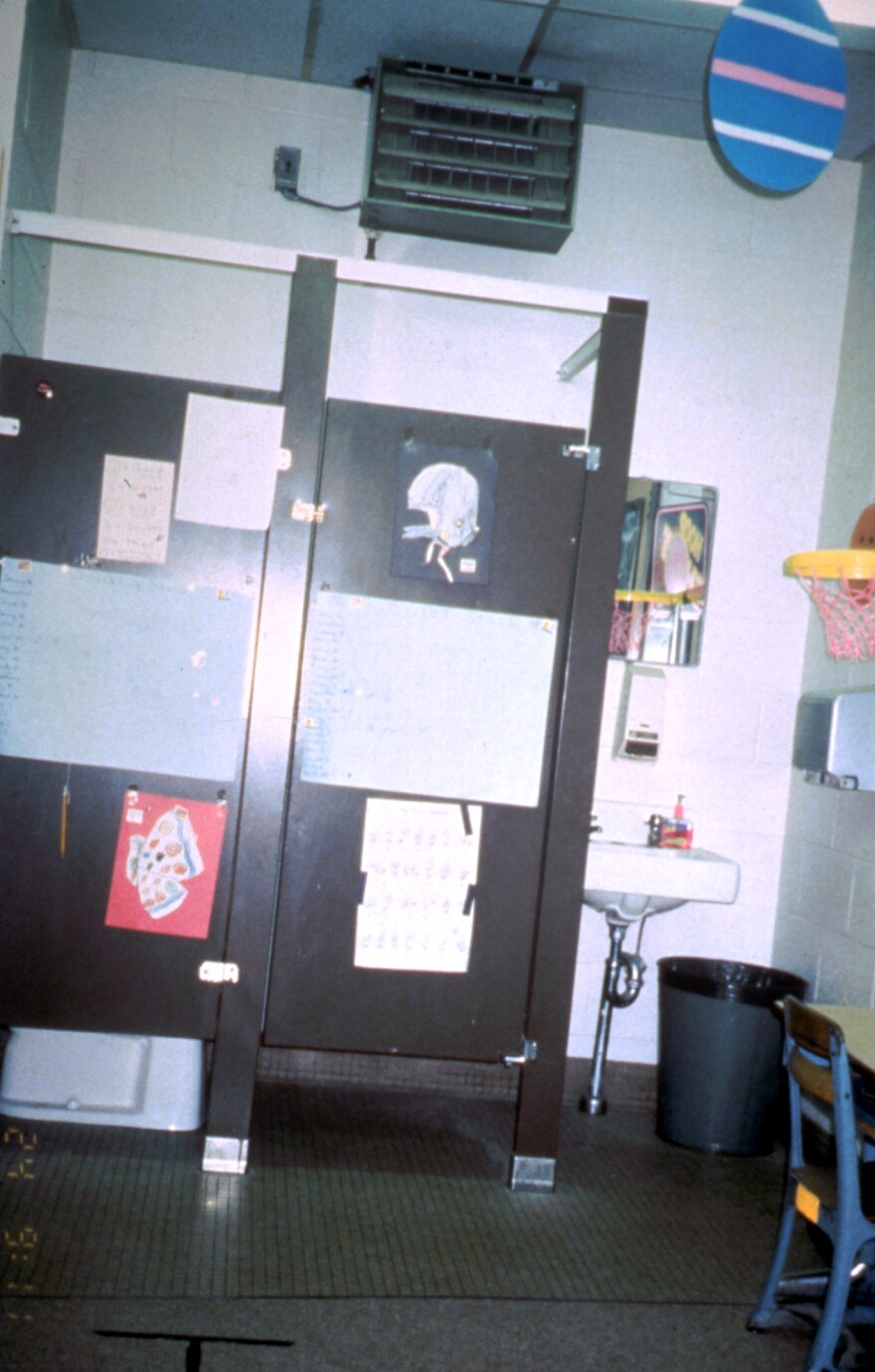

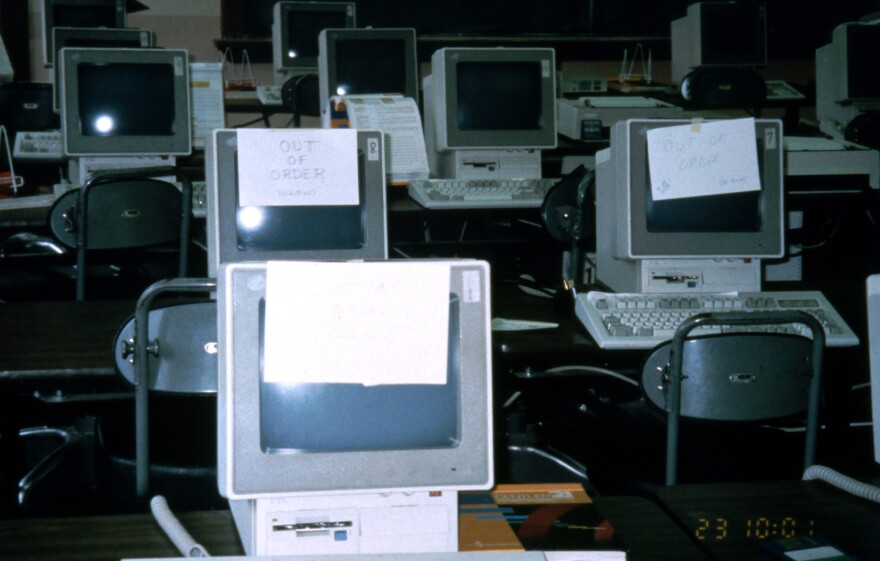

“Allenstown used a converted bathroom for one-on-one sessions for special ed children,” he remembers. “The most stigmatized small child in the school literally went to class in the bathroom. That still haunts me.”

In Claremont, students read from textbooks so old that the chapter on space wondered whether someday humans would send an astronaut to the moon.

In Franklin, when students tried to play basketball in the gym, the vibrations would unleash asbestos onto the band class below.

The Claremont lawyers argued that students in these property-poor districts - and at every school in New Hampshire - had a right to an education, and that reliance on local property taxes to fund it led to unconstitutional variations in tax rates across the state, depending on towns’ property values.

In its 1993 decision, the Supreme Court agreed, writing that the state was obligated to provide "a constitutionally adequate education to every educable child in the public schools in New Hampshire and to guarantee adequate funding."

This was big, but it didn’t solve the problem of how the state was supposed to guarantee funding.

So the Claremont lawyers went back to court.

The Road to Claremont II

Teachers were at the center of a new six-week trial in 1996.

Rhetta Colon, of Meredith, was one of those who testified. She taught English for nearly 40 years - first in Franklin, then in Gilford. One of her main reasons for leaving Franklin was that she couldn’t earn enough money to make a down payment on a house.

On the witness stand, Colon testified that when she taught at Franklin High School, she was in charge of hiring teachers.

“I would stand at the counter and open letters of application and I remember very clearly the principal saying to me: ‘Don’t bother scheduling interviews with anyone who has more than a bachelor’s degree and five years of experience because we can’t afford to pay them.’”

A couple of years later, Colon moved to Gilford High School, in a wealthier town with higher pay. There, she was also in charge of hiring.

“I remember when the same situation happened at Gilford I was told make sure that anyone you interview has at least five years of experience and a master’s degree,” she said. “And the disparity was obvious.”

This trial got national attention and the case eventually ended up in the Supreme Court. In 1997, it issued its decision, known as Claremont II. It said the state has a responsibility to pay for an “adequate” education, and the taxes to pay for it have to be fair and uniform across the state.

It led to immediate backlash in Concord. Democrat Jeanne Shaheen, who was then serving as governor, said she disagreed with the decision. Others said the court had overstepped, by forcing lawmakers to raise more money and more taxes, maybe even an income tax.

How to Pay For An 'Adequate' Education

After Claremont, lawmakers got to work. David Hess, a former Republican state representative from Hooksett, remembers they calculated they needed to increase spending by about 25 percent to meet the court’s mandates.

“When you have to find an additional 25 percent more money than what you appropriated last year, out of our tax structure, that is a major issue, he says.”

Lawmakers increased various taxes - business, real estate, car rental tax - and then they created something called the statewide education property tax, or SWEPT.

This money - currently $363 million annually - is technically raised and kept locally through property taxes, but it’s considered a state tax, so it lets the state fulfill its obligation to pay for an “adequate education.”

But defining “adequate” was another hurdle.

“We were all writing on an open slate,” Hess recalls. “Nobody had much experience in addressing the issue.”

Graphics by Sara Plourde / NHPR

"I think it's a strong feeling of ... desperation."

Lawmakers came up with a formula based on expenditures from certain districts in New Hampshire where students met academic standards. The number came out to about $3,400 per student per year. They threw in some more if students received special education, or if they were learning English, or if they were low-income.

State education aid increased - not including SWEPT, it more than tripled. But lawmakers were constantly tinkering with it. And making substantial changes felt impossible, because everyone was focused on protecting their own town’s money.

“Whenever an education bill would come to the House floor or Senate floor, the first thing any member would do would pick up the spreadsheet,” Hess remembers. “Is it going to get more money or less money? If it gets more money you have good chance of getting a vote for the bill - if less, chances are you're going to lose a vote for the bill.”

A Years-Long Battle For Dollars

Things got tougher during downturns in the economy. In the recession, lawmakers slashed other sources of education funding, like school construction aid and teacher retirement benefits.

But the formula Hess and other lawmakers helped create is still intact. One of the main debates today is whether it’s enough.

Schools now spend an average of over $18,000 per student per year - most of this funded by local property taxes. Hess and other fiscal conservatives argue that much of this money is for resources that go “above and beyond” the definition of adequacy.

But others say it’s time for the state to step up, or the ConVal lawsuit filed last week could be the first of many.

“You just have to look at the number and understand what it costs to provide sort of a basic education,” says Freeman, the school superintendent in Pittsfield. “It just seems so absurdly inadequate that the joke of it is that it’s called an adequacy grant.”

Freeman says things today aren’t much better than when Pittsfield and others sued the state over 20 years ago. Despite the big boost in state aid in the aftermath of Claremont II, the state still pays for less than 20 percent of the overall education budget.

“I think it’s a strong feeling of, in some cases, desperation,” Freeman says of Pittsfield and other districts. “People are really at the end of a road here that needs to change.”

The ConVal lawsuit asks for the state to triple what it sends to districts in adequacy aid. And many bills in the State House are looking to boost that amount too. That’s going to take a lot more money, and the battle to figure out where that comes from has only begun.

(This next report in the "Adequate" series will air March 28. Contact Education Reporter Sarah Gibson: sgibson@nhpr.org)