Is the North Country moving towards an ATV-based economy? And if it is, what does that mean for residents who aren't sold on the idea?

This is the third episode of Word of Mouth's North Country series. Listen to the first installment, "Where Does the North Country Begin, And End, in N.H.?" and the second, "Mill Complex".

It’s a warm and cloudless Friday in late May in Gorham, New Hampshire. This town, with a population of just under 3,000, will come close to doubling in size this weekend. That’s because the surrounding ATV trails are now open in Coos County.

“You probably don’t think I would be one of the guys to listen to (NHPR) but I do! I get a kick out of it,” says Ray Bergeron, owner of White Mountain ATV Rental

Bergeron’s a self-proclaimed gear-head and has been racing motorcycles for almost 45 years.

The shop, located on Gorham’s Main Street, is modest, small and functional, and has a sprinkling of Bergeron's personality throughout, like a riding suit made entirely of bubble-wrap he reserves for his “trouble customers.” There’s a classic rock station playing in the background, 8x12 framed pictures of engines, and trail signs that read things like ‘Stay on the Trails or Stay Home.’

I’m here because we are about to go for a ride: my first ever on an ATV. And before I can even get comfortable, Bergeron starts the engine and pulls out from the parking lot onto Main Street.

“So you’ve got guys my age that when we stop at the green lights, we stop and look for cops over our shoulders,” Bergeron says. “Old habits never die, ha!”

There’s something else I should mention.the ATV we’re in might not be what you’re picturing.

“We’re in a Yamaha X4, four seater, it’s a sports utility model,” states Bergeron.

This X4 is also referred to as an OHRV or side-by-side – side-by-side because the seats are, well, side-by-side — it looks like something between a jeep and a souped-up golf cart. At first, I was a little hesitant, especially once we left the parking lot for Main Street. But the ride was a uniquely liberating, like taking a convertible into the woods.

We jet from the downtown area, bustling with restaurants and hotels, to the major thoroughfare in town, Route 2. After a few minutes, we turn into a parking lot and then onto a dirt road - a rail trail.

On one side of the trail is the Androscoggin River, once one of the country’s dirtiest rivers but now much cleaner after a major clean-up. On the other side, rising green cliffs of maples and spruce lead into Maine.

Back on the trail, there’s a buzz among riders who’ve anxiously waited for this weekend. That includes Berlin residents Mike Bissone and his son, Jayden.

“I bought my first one in 2015,” says Bissone. “I ordered a four seater loved it, bought this one, and I bought my son a 1000S. And we’ve got about $75,000 invested in these things.”

ATVs are big business in Coos. The X4 (which Bergeron offers for rent in his shop) retails for over $17,000 new off the lot. In the North Country, riding is bringing new life and new money to the once bustling mill town.

But not everyone is happy with the change.

"If it is boosting the economy, it's boosting the economy at our expense... so that these machines can enjoy the town." -Sandy Lemiere

“Today, I can’t be sitting outside with company, it’s noisy,” says Sandy Lemiere, long-time Gorham resident. “I’ve just got this little window cracked and you can hear the noise. The windows are closed from morning till night until they’re off the trails then we open our windows if we want fresh air, you know?”

As always on Word of Mouth, this story about ATVs started with a listener question. And on this topic, it came from many, many listeners.

People wanted to know: how can the North Country emphasize a low-carbon future if it sells out on ATVs? How will it deal with the noise pollution? And what does this mean for the culture of the North Country?

Abby Evankow lives in Gorham near Moose Brook State Park. She says she and her husband didn’t buy land and build a house next to the state park to live by a motorized trail and hear motors all day.

But that’s what happened after the town opened its snowmobile trails to ATVs against the will of some residents.

“When I looked at the Select Board minutes, at that point I was working out of town so I wasn’t able to attend the meetings, there was no mention [that] there was any opposition whatsoever to expanding the ATV trail,” Evankow says.

Now, you might think this is another “Not-In-My-Backyard” story and dismiss Abby’s concerns but ...

“Would you want this by your home from May 23 to November 4, the warmest part of the year when you want to be outside and get fresh air?” asks Evankow.

Most riding weekends,anywhere from 800 to1000 riders pass through the area. This weekend, organizers expect two to three thousand riders, many headed right for that famous Route 2 parking lot, the same one where Ray Bergeron took me out for a ride. That spot is the southernmost access point to the state’s Ride the Wilds trail, 1,000 miles of interconnected ATV trails in Coos County.

There’s been a lot of reporting on this controversy and the Route 2 trailhead specifically, but for Abby Evankow and the people that live close to the trail, there’s still a big part of the story the media is getting wrong – including NHPR.

“[NHPR] came up here and talked to some people who live on Route 2, which is now open to people on ATVs,” Evankow says. “And the title was ‘Culture Wars,’ and that’s just wrong because several people who live along the ATV trail, in Gorham, own and ride ATVs. So it’s about where the trails belong.”

Steve Clorite, the President of the Androscoggin Valley ATV club, agrees.

“We should not be everywhere, we do not want to be everywhere, riding roadways actually is not fun for us,” Clorite says. “We really wanna be off the roads in the woods.”

Clorite is an ideal diplomat for any riding club. He matches his enthusiasm about the future of riding in Coos, with concern for those who live by the trailhead.

“The way that [riding] took off in 2013, 2014 was unanticipated by a lot of the community and by the clubs,” Clorite confesses. “So the amount of activity... we really had no way to gauge what impact that was gonna have on the community.”

By community, he means both those living on Route 2 and the local economy.

“By opening the roadways it was really like flipping a lightswitch,” Clorite says. “The housing market went crazy and businesses started taking off and the events became a lot more successful because it was just so welcoming to the OHRV community.”

Clorite moved to Berlin from the Lakes region in 2013, right as the Ride the Wilds trail opened. He bought a three-family rental property. It needed a lot of work but he saw a convoy of riders in his rear-view – riders who would love the chance to drive from their yards straight to the trails.

“If you look at the values of our properties now, our 20k building is probably worth 80k and that’s just from 2013,” says Clorite. “In addition, we’ve seen the rents go up. A unit I used to get $550 a month that included heat and hot water, now I get $750.”

Opening a trail system for ATVs isn’t unique to New Hampshire. In West Virginia, old coal mining land became 300 miles of trails known as the Hatfield and McCoy trail in 2000.

In its first five years, the trail generated an estimated 25 million dollars into the local economy. Last year, 50,000 trail permits were sold in West Virginia, 80% from out of state.

I was told around the same time the Hatfield and McCoy trail opened, Coos County saw a jump in ATV permits. But the county didn’t have anywhere for them to go, as up to 80% of New Hampshire’s ATV trails fall on private land. And there definitely wasn’t a trail system like down south.

In 2005, Bob Danderson, then-mayor of Berlin in 2005, had an idea. He knew the town was sitting on an underused, 230 acre city-owned park, centered on Jericho Lake. He combined that with an abutting 7,200 acres from the state. Town and state working together led to the creation of a rider’s paradise: Jericho Mountain State Park.

"I knew that this property was going to have trail access, always and forever to the Jericho Mountain State Park." -Steve Clorite

The opening day of every riding season is a time of celebration for ATV enthusiasts and some local business owners. Dozens of pick-ups with trailers, a fleet of dirtbikes, ATVs, and side-by-sides line up before the sign-in tent. License plates from all over the northeast, from New York to Maine, dot the streets.

Many people have come together to make this day happen, but a lot of credit goes to Paula Kinney, Executive Director of the Androscoggin Valley Chamber of Commerce.

Kinney could be considered the ATV ambassador of the area. She believes the county is just scratching the surface of its true riding potential.

Kinney grew up with ATVs in her family. Back then they were functional - used for hauling lumber, food, anything too heavy to carry. You could get in and out of the woods easily, places your truck couldn’t go. These were a different beast than the ATVs today - slower, no high-end suspension, no plush bucket seats. If you went for a longer ride, you’d feel it the next day. Riding was different.

“It wasn’t so family oriented, and girls driving, and the women out there, and the grandparents out there,” says Kinney. “The side-by-sides have really changed it.”

Paula Kinney grew up right next to the Brown Company paper mill in Berlin. She had a front-row seat to the changing economy as the mill struggled to stay afloat, changing ownership time and time again.

After 20 years working at a manufacturing plant, she, like so many mill workers in town, lost her job.

“I was kinda devastated when I lost my job after 20 years. It’s all I really knew,” Kinney recalls. “I worked in a manufacturing plant, I was a secretary for it but still, I saw all those women lose their jobs and they were all hardworking women but that’s what they knew. They knew how to do manufacturing work. It was a little scary.”

Kinney started volunteering with the local Chamber of Commerce. She organized garage sales and bake sales, anything to bring in new money. Eventually, the chamber offered her a paid position. Then she became its Executive Director.

I wasn’t sure if what Kinney loves more: ATVs, or how much they’ve done for Berlin and Coos County. But one thing was clear: the folks who came out opening day love to ride.

“Oh yeah, as much as we can come up here we’re up here doing this, almost every weekend from Memorial day up till Columbus day,” says Greg Miller of Salisbury.

Three generations of Millers drove up this morning.

“Our kids just went by on two other 4 buggies that we bought, so it’s us, our two kids their spouses, and our four grandkids that do this,” says Kim Miller. “It’s a family affair.”

I ask if she has any concerns about her grandchildren in those buggies.

“We have an 18-month old and she actually started riding last year,” Kim Miller says. “She’s right behind us and when these things start up , they’re running. They know to get their helmets on, their goggles on, yup.”

A lot of people might be thrown off seeing an 18-month old with her little helmet poking out from the backseat. And some riders told me they had concerns about the age of riders.

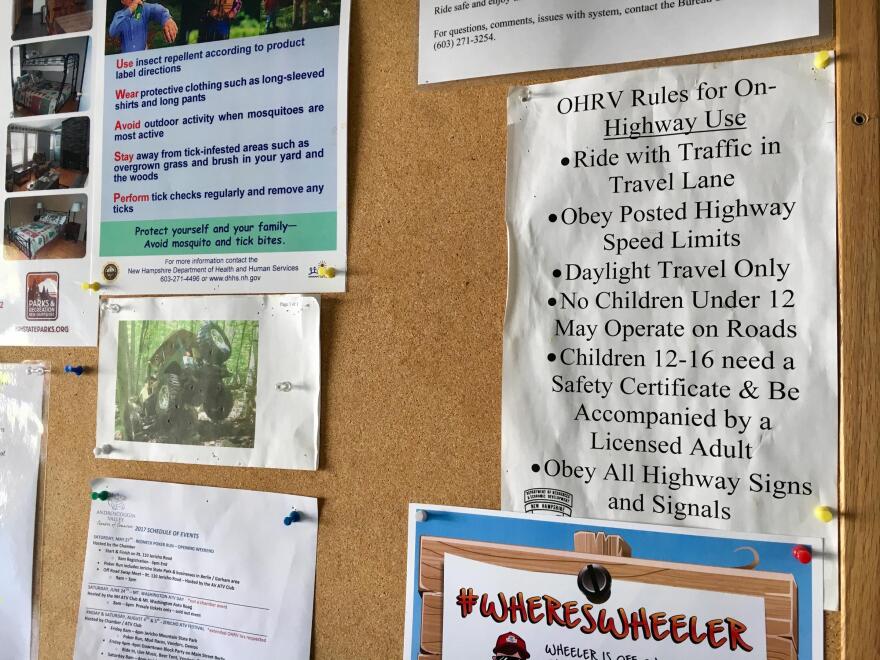

As of right now, kids as young as 12-years-old can ride on approved state roads and trails without a license if they’ve taken a safety class and are with an adult. At 14, they can drive by themselves but need a licensed adult close by.

To state the obvious, that’s years before they’re legally allowed to drive a car on the same exact roads with a license.

For Paula Kinney, these are small details that need to be ironed out so they can keep building an ATV paradise.

“But it all comes down to though, the cash registers are ringing. I’m sorry, economic development,” Kinney says. “I took my husband for a ride in Gorham yesterday and I said I gotta go take pictures of the hotels and restaurants and he goes ‘you’re crazy, what are you doing?’ And I said ‘it’s economic development! I take pictures and keep showing people what it’s doing.”

This isn’t the first time Coos County or New Hampshire have debated land use, noise, and motors. Forty years ago, the conversation was centered on snowmobiles.

At the time, residents complained that out-of-town riders drove in, made all kinds of noise, ignored property rights, and destroyed precious snow-covered crops. Riders also had to figure out how to share space with non-motorized recreation including cross-country skiers and hikers.

“Snowmobiling exploded years back and they had to get a harness on it. They had to put a leash on it and reel it in and get it organized and it’s a very organized thing now,” says Bobby Rodrigue, a member of the White Mountain Ridge Runners Snowmobile Club

Everyone close to the ATV scene, proponents and opponents alike, know the area’s top asset is its wilderness: the natural landscape and scenic views.

Rodrigue thinks that one way or another, this whole ATV issue will figure itself out, just like it did for snowmobiles It’s too big of an opportunity not to.

“This is as big as Sturgis is to motorcycles, we’re getting known as a destination,” Rodrigue says. “We’re swamping the Hatfield and McCoy’s in mid-states, we’re on the map for what we do here for ATVs. We’re one of the first communities to allow ATV access all through town.”

For some people, though, there’s a reason why ATV access isn’t allowed throughout towns.

“We were never notified as abutters, by the town or the state, that we were gonna have these on the roads and these machines going by the house,” says Sandy Lemiere, who lives on Route 2 ,a few hundred feet from the trailhead.

To her, ATVs and snowmobiles aren’t a fair comparison. For one, snowmobiling happens in winter months when most people are indoors, windows closed, and you also won’t find as many snowmobiles rumbling down Main Street.

Lemiere lives in the same house her father built in 1942, the year she was born.

“It’s amazing what it was like then to what it’s like now,” Lemiere says. “There’s no comparison at all.”

The neighborhood has changed in so many ways since her childhood. That includes the side street next to her house, which didn’t exist when she was growing up

“We’d go down that little patch of grass and rocks, and whatnot, and we’d cross the barbed wire fence and go and chase the cows and the bulls,” Lemiere says. “My mother used to get so upset with us because we ruined so much clothes.”

Back then a few passing trucks were loudest noise around.

Lemiere is retired now. She’s gotten used to the increasing traffic over the years. But ATVs are a different story. She says her neighbors wake up gritting their teeth every morning. When I was at her house, we didn’t just hear the noise of the ATVs passing by, but also felt a noticeable vibration. They literally work your nerves.

Lemiere says she’s okay with the roads, even Route 2, being open to riders. Her beef is where the trailhead is located: right in the middle of her neighborhood.

“All we want is the trail moved out of our neighborhood, but it’s like we’re asking them to shut down all the trails,” says Lemiere. “The ATV riders will even tell you that, oh you want to shut down everything. No, that’s not what we want. We want the trailhead moved out of our neighborhood. There’s gotta be a better place for it.”

Last year, the neighbors reached a breaking point

“We’re at this point now where the town doesn’t listen, the state doesn’t listen, nobody cares, but we’re not giving up,” Lemiere explains. “We’re continuing to fight because we want our neighborhood back. That’s what we want. We want our peace and quiet. We’re going to trial in October.”

Sandy Lemiere and twelve other residents filed a lawsuit against the town of Gorham. They want the town to enforce its zoning ordinance and remove the trailhead completely. She says with the lawsuit in the air, she feels targeted.

“Last summer I was mowing my lawn...and I was coming up towards the sidewalk, and this ATV, he must have known who I was... but he almost stopped, looked at me, gave me the finger and took off,” Lemiere recalls.

There has been some support, however, even from riders.

Last summer a Berlin resident, who frequently rides past her house, told Lemiere she didn’t know how bad things were until reading about it in the local paper. She said she was rooting for them to win the lawsuit.

“If I had to say my piece I would say, the town officials, the state officials: come down to our neighborhood spend a day with us, spend a day with us, and hear what we have to put up with. Then you’ll know what we’re talking about,” says Lemiere. “But don’t tell us in Concord that you know what we have to go through. You don’t know unless you come here.”

Steve Clorite, the president of the local ATV club calls places like Route 2 in Gorham “hot spots”— places where there’s embedded friction over trails and residents quality of life.

And in some of these “hotspots,” the story is playing out differently. Residents feel like they’re finally getting their neighborhoods back.

LOST NATION

“There’s three acres of organic apples and we grow medicinal herbs and we’re surrounded by state forest,” says Michael Phillips, owner of Heartsong farm and Lost Nation Orchard in Groveton.

Phillips’s big white beard muffles his voice. The earth matted on his worn blue jeans is the same earth under his nails. Thirty years ago, Phillips and his wife Nancy found an abandoned barn settled between mountains and a babbling brook in the North Country. They’ve been here ever since.

“So there’s lots of forest around, lots of peace and quiet, and the occasional ATV,” Phillips says.

About 8 years ago, the abutting towns and villages of Northumberland, Lancaster, and Groveton agreed to open Page Hill road to ATVs. This would, in effect, connect the towns of Groveton and Lancaster, and open up the area to riding the same way Berlin connects to Gorham and beyond.

The connector ran right through Phillips’ neighborhood.

“There were lots of promises that this was just temporary,” Phillips says. “In a year or two, maybe three years we’ve got plans, we know how we’re gonna get through the woods. We’re gonna have a real trail,and we won’t be on the roads.”

The area in and around Groveton is generally wetter than further south, making for a more sensitive ecology. It’s also not ideal for ATV trails expecting to see hundreds of riders per day. This places more riders on roads.

A few months ago, the local Select Board closed the connector, cutting off trail access south of Groveton.

But as ATV momentum picks up around the area, the potential to jump start the economy of another old mill town means the connector may not stay closed for long.

“The majority of our neighbors on Lost Nation don’t want ATVs coming right by their property and disturbing the neighborhood the way it does,” says Phillips. “And I’ll be honest, right now we’re on the level of 200 to 300 ATVs a day every weekend – which is nothing like up north where it’s around 800 to1000. But knowing what’s up north, and what could happen here if this idea of an ATV economy as our last salvation takes hold, I mean, that would destroy the dream that Nancy and I had and everyone else who’s moved here and lived here for years and years.”

Michael and Nancy Phillips host weekend events on their property, both day-long and over-night. Their workshops focus on organic agriculture, healing herbs, and Nancy’s “Radiant Women Weekends.”

He says he hasn’t noticed if fewer people are visiting the orchard, but he does know that retreat numbers drop during summer weekends. And Phillips pushed back on the idea that ATVs are an economic silver bullet.

Sure, he says, gas stations, hotels, and ATV shops will see a boost. Some restaurants, too. But he thinks the area has lost other, non-motor-centric tourists because of the shift.

“The other big issues is that it takes a lot of money to maintain trails that are destroyed by machines whose function is to destroy ecosystems. I’ll just be blunt about it,” Phillips says.

Eight years ago, right around the time Page Hill was opened to riding, Phillips was elected to the local select board. He got involved because he felt like those early conversations were missing a voice.

“But I also know that when I feel strongly about an issue, and my neighbors feel strongly about an issue and it’s difficult as a resident to go to a Select Board meeting when 50 to 60 ATV’ers have come and speak up and say I really am not happy about this,” Phillips says. “I’ll do that role as a selectperson, someone sitting up there at the table. I’ve done that role.”

And while ATV’ing is having a moment in the North Country, Phillips thinks the major draw is still the area’s natural beauty.

“We get letters written to the select board, and some are, ‘I want to ATV, it’s now a 5-year family tradition to get in our ATV and run to town and look at the covered bridge and come home,’” says Phillips. “And I think, well, we have a 30-year tradition here on our farm where we listen to the birds sing.”

Northumberland Select Board member Chris Wheelock says that Groveton is not anti-ATV but he contends that the landowners also “deserve some quiet.”

Wheelock has talked directly with riders and clubs. He’s known some of the riders since kindergarten.

“We have asked for them to come up with a trail system that went through the woods. The clubs are ultimately the ones responsible for finding a trail,” Wheelock says.

There are three clubs in the area: North Country ATV, the Strafford/Gateway Trail Riders, and the Kilkenny Club. They knock on landowners’ doors and ask for permission to ride across their property.

"Some people think this is a burden and it’s a crime to some of these people, but to other people we’re trying to make a living up here." -Bob Reynolds

“It’s kinda one of those things where you have to go to the town office, you have to get tax maps, you’ve got to find these people, it’s a lot of online searching,” says Bob Reynolds, Trail Boss for the Kilkenny Trail Riders and parts manager at Dalton Mountain Motorsports.

Reynolds says he’s put in over 100 hours in the past year talking to landowners to try to keep the road open.

He’s a serious rider. He’s a three-time motocross champ in Vermont. It hasn’t come without injury. Reynolds has broken 16 bones, including both femurs, and was temporarily paralyzed for four months after a crash. But you still can’t keep him away from motors.

“The best ride I’ve ever been on was a second date with my fiancé,” Reynolds says. “I had a side-by-side at the time and it was a great summer night, sun set, the whole deal and I’m saying if she’s into this then maybe she’s the one. I just knew and that was six years ago in July. We’re getting married this July and it’s awesome.”

Reynolds gets just as excited when he talks about the Ride the Wilds trails. Those thousand miles of interconnected trails are something he worries about losing with the recent road closures.

Reynolds, like Paula Kinney, sees a North Country that could become a rider’s paradise.

“This is, we have something very unique, I mean this is the best riding on the east coast,” Reynolds exclaims.

When I first called Dalton Mountain Motorsports to talk with Reynolds, the line was busy. Turns out he was on the other line with a group of 15 riders from New York. They wanted to come up for the weekend. That it until he told them that Page Hill and Lost Nation were closed to riders.

“And it’s disappointing to hear from a business standpoint, from these people that have to hotel, that a group of people from New York, which can’t ride side-by-sides over there — it’s illegal to ride there because of the weight. They don’t want the weight of these vehicles on the trail because of the weight,” says Reynolds. “They drive six to eight hours to come over, have a good time and ride, pay room and meals [tax], pay gasoline [tax], pay registration to the state of New Hampshire, and they basically went somewhere else.”

Reynolds has lived in the area his whole life. His dad worked over 40 years in the Groveton mill. He worked 13 years there until it shut down in 2007. The thought of losing business, of paying customers, in Groveton, a defunct mill town, population 1,100, is something he can’t accept.

“Some people think this is a burden and it’s a crime to some of these people, but to other people we’re trying to make a living up here,” Reynolds says. “We need to move on. he paper mill is gone. I’m on plan B here. This is what we’re doing. I just think that this is a gift.”

There are residents on Page Hill and Lost Nation that bought into the neighborhood for access to the trails. Chris Wheelock says some businesses have told him they’ve taken a hit.

I also talked to residents that asked not to be recorded. They say they’ve spoken out at town meetings and have felt threatened and targeted for doing so.

This includes Doug Menzies, who lives on Page Hill Road. He said when the roads were first opened, he was neutral on the issue.

Then riders began speeding down Page Hill all through the night. The family’s garden was constantly covered over in dirt kicked up by ATVs. And one day, two years ago, a group of a dozen or so ATVs went by, fishtailing. A side-by-side lost control and rolled onto its roof. Menzies had to help the rider out.

Since then, Menzies says he’s been shouted over at town meetings, and that his concerns are always met with confrontation. The air stays thick in Northumberland’s town hall when talk turns to ATVs.

The North Country has some big decisions to make. How many of its economic eggs will they put in the ATV basket? The over-reliance on one industry is a familiar story in Coos County. And depending on that, is a low-carbon future a priority? Parts of the North Country have always been a tourist destination for non-motorized recreation.

THE CIRCLE OF HISTORY

“I’ve learned that you need to look back every so often, so when you come back down you’ll know which way to go,” says Edith Tucker heading down to Colebrook Falls in Randolph.

Tucker is a two-term State Rep from Coos, and a longtime local reporter.

Colebrook is a small waterfall, maybe 20 to 30 feet tall. A dirt path eventually leads to a bridge that extends over a shallow brook. The bridge memorializes the town’s centennial. On a rock, there’s a worn plaque with a name: Louis F. Cutter

“This is my grandfather’s name,” Tucker explains.

Next to Cutter’s name is Eldredge H. Blood, the man who helped Tucker’s grandfather design the bridge.

The bridge is narrow. But even narrower are the pillars measuring two feet apart from one another. It’s a tight fit for a reason, Tucker tells me.

“This is because motorcycles had become very popular in the twenties because of their use in World War I, and so grandpa designed this so that motorcycles couldn’t go over this and couldn’t go on up the mountain because that was a problem,” Tucker recalls. “And over time, people saw where motorcycles should go and where they shouldn’t go. And that’s why I think there’s a sort of lesson to be learned with ATVs. We’re still in the early days of people coming up in numbers to be on ATVs. And we’re gonna have to work up here in Coos where they’re welcome and where they’re not.”

Just this year, new legislation was proposed that said abutters would have to be notified before ATV trails opened up next to their homes. This wasn’t the case with the trails in Gorham and throughout much of Coos County. It would also require a public hearing with at least two weeks advance notice.

Abby Evankow from Gorham said this wasn’t a culture clash, pointing out lots of residents, even those on the Route 2 trailhead own ATVs. But that’s not entirely true.

“I think in the long run we’re gonna talk about distance and whether ATVs need to have unfettered thousand mile access all at once or if we can have centers and places that are separate from residential neighborhoods,” says Edith Tucker. “But it’s gonna take time and it’s gonna take some clever people who can facilitate the discussion.”

Tucker doesn’t think the state has the ability to fix the situation. That means it’s going to depend on locals to figure it out in towns, neighborhoods, and streets.

The North Country is grappling with a question its faced a number of times in the past 100 years, from motorcycles to snowmobiles, and now to ATVs: if a defining part of the North Country is it’s landscape, is there room for everyone?

On the next episode of North Country series: the story of Internet access. Listen on NHPR on Saturday, July 20 at 11am.