A number of New Hampshire towns is looking at community power as a way to provide energy that could lower costs for residents, help tailor their energy mix, and provide room for innovation. We explore how community power came about, how it would work, and the challenge to it in this year’s legislative session.

Airdate: Monday, February 22, 2021

GUESTS:

- Doria Brown - Energy Manager for the City of Nashua, where she works on energy efficiency projects, greenhouse gas accounting, and energy procurement.

- Henry Herndon -Citizen Volunteer on behalf of Community Power Coalition of New Hampshire.

- William Hinkle - Media Relations Manager for Eversource.

- Donald M. Kreis - New Hampshire’s Consumer Advocate. Kreis represents the interests of residential utility customers before the NH Public Utilities Commission and elsewhere.

This show is part of By Degrees, NHPR's climate change reporting project. Click here to share your ideas for future coverage.

Transcript

This transcript is machine-generated and will contain errors.

Laura Knoy:

From New Hampshire Public Radio, I'm Laura Knoy, and this is The Exchange.

Laura Knoy:

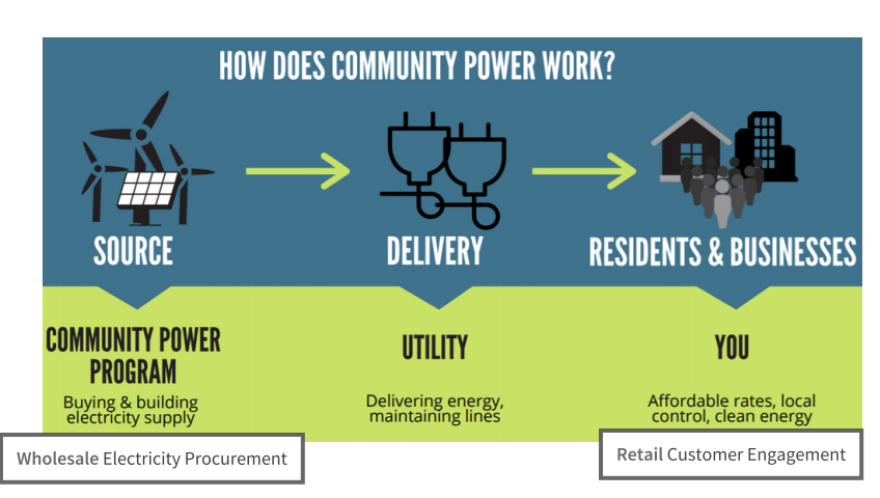

A handful of New Hampshire cities and towns are looking to adopt what's called community power, a 2019 law allows municipalities to buy power in bulk on behalf of their residents. Utility companies would still distribute that energy because they own the wires and poles that transmit electricity to your house. Today on The Exchange, how community power works, who's joining in and what the concerns are expressed now in a bill before the legislature. Our guests are Donald Kreis. He's New Hampshire's consumer advocate representing residential customers before the Public Utilities Commission. And also with us, Henry Herndon, citizen volunteer on behalf of the Community Power Coalition. So before we get into all the details, gentlemen, you know how this works. Henry, you first, what's the bigger goal here? Why do this?

Henry Herndon:

So why do community power, so the goal of community power is to, through local control, give cities and towns access to competitive markets for energy services? So, as you said, you can pool together the buying power of all the residents and businesses in a community and give that community the ability to achieve its energy goals. So some communities might prioritize lowering energy costs, while others might be more interested in becoming more energy self-reliant by building their own energy systems or potentially developing renewable energy and even other communities still, they might be focused on innovation and new technologies like energy storage and electric vehicle charging. So all of these can play a role in community power and really enable our cities and towns to become sort of laboratories of innovation, sort of pursuing their own energy goals and priorities in accordance with what's most important to their community.

Laura Knoy:

And is this, Henry, a push back to the idea that utilities haven't been engaged partners with towns in terms of achieving their energy goals?

Henry Herndon:

I wouldn't describe it as a pushback, Laura, but I would describe it as an innovative approach to move the state forward and modernize the electric grid and develop renewable energy here in the state in a way that goes sort of around the utility, because utilities tend to be slower and less inclined towards innovation. And I've got to say, lower up front to just to be candid with you, I'm a little bit frustrated and I'm a little bit angry this morning because all the progress we've seen cities and towns work towards in terms of community power could come to a grinding halt. What we've seen is community power has run up against corporate power at the state house. And one corporation in particular, it's pushing for legislation that could really undo all of the good work that is happening around community power.

Laura Knoy:

Well, and you're talking about Eversource. And we will have a representative from Eversource with us later in the hour. A question for you, Henry, and then I want to bring you in too, Don. How much has the debacle in Texas affected this conversation? I'm wondering if people are looking at what happened there and going, oh, OK, we still have heat, light, you know, power. Let's not mess with anything. What do you think, Henry?

Henry Herndon:

I think reliability is incredibly important, and I think it's what the utility companies do very well. They maintain the poles and wires and they provide an essential service and it's an important part of the system and it's essential. The challenge comes when there's overreach by some of the utilities to stifle progress and stifle some of the innovation that could really bring lots of value, lower costs for our citizens, give customers more choice and more options, and allow folks to innovate and generate more renewable energy.

Laura Knoy:

So, Don, to you, what evidence is there that community power can provide some of these benefits that Henry talked about, you know, greener energy, achieve your energy goals at the community level, lower prices? I mean, who's done this? And and has it worked elsewhere?

Donald Kreis:

Yes, it has. The place I would suggest everybody take a look is Cape Cod, where the Cape Light Compact has been going for, gosh, I think it's something like 20 years now. Every community on Cape Cod and I believe several that are Cape Cod adjacent participate. And it has been enormously successful in saving customers money. You know, we in New Hampshire restructured our electric industry beginning in 1996, and the ratepayers of the state have paid dearly. I mean, we're talking billions of dollars, making the utilities whole for offloading their power plants and their power commitments. That is paid off really well for the large commercial and industrial sector because they have a lot of buying power in the wholesale markets. It has not paid off for residential customers. I think community power could finally deliver the goods for the state's residential electric customers; I'm very excited about it.

Laura Knoy:

So beyond possibly lower prices, what other goals are at play here, Don?

Donald Kreis:

Well, of course, as the state's residential ratepayer advocate, I am all about low prices. That's my big goal. But I think in general, I think communities can pursue a broad based energy agenda. And Henry already mentioned some of them. I mean, there's renewable energy. There are flexible energy services. There are opportunities for time of use rates. I mean, communities can pursue, I would say, comprehensive energy policies. And because it has been hard to cause reform to happen at the federal level and even the state level, I think the municipal level is a fruitful realm for people at the local grassroots level to pursue energy goals that their communities find advantageous and necessary.

Laura Knoy:

So, Don, do communities have the technical expertise to carry this off? I mean, you don't need me to tell you that the electric grid and feeding it and making sure it's always there is incredibly complicated.

Donald Kreis:

Well, you know, it's interesting because that was my initial reaction when I first heard about this. I said to myself, do I really want the people who are fixing the potholes on my street to be supplying my electricity? Electricity is complicated as we've seen in Texas over the last week or two. But, you know, communities like the Community Power Coalition of New Hampshire are combining forces and they can bring in the expertise that they need from elsewhere. And I don't think it's going to be the same people who fill potholes that will be making sure that your electricity is what you want it to be.

Laura Knoy:

Henry, can you address that as well, please?

Henry Herndon:

Yeah, it's a good question, Laura, and it there's a couple of pieces here, really what you're doing is you're giving the expertise of the competitive marketplace to local government. So not every city and town is going to staff up its own power procurement office. But what they're going to do is they're going to gain access to the experts in the marketplace, be able to choose from a number of different service providers and use that expertise to innovate and to lower costs. And one model in particular, I think we may get to later is the Community Power Coalition, which is pooling resources together to share expertise in a transparent and accountable way and make that available via a public nonprofit to all cities and towns who would choose to join that organization and work with them on their community power programs.

Laura Knoy:

So that's where the expertise would come from, Henry.

Henry Herndon:

Yes,

Laura Knoy:

You know, Don mentioned Henry a moment ago, the massive deregulation effort that New Hampshire undertook about 25 years ago, how much, Henry, is community power connected to that movement 25 years ago? What's what's the connection between then and now?

Henry Herndon:

It's a good question, Laura. So just a brief recap, in 1996, New Hampshire, we led the nation in deregulating our power sector and, I've got to give a shout out to honorable Senator Jeb Bradley and the honorable Clifton Below. These these men got together and and put forward bipartisan legislation to restructure and deregulate the power sector, sell off the power plants and bring competition to the marketplace. And the purpose there was twofold. It was bring competition to wholesale electricity markets and retail electricity markets. And we achieved half of that. We got halfway there with restructuring where we sold off the big power plants. We get more generators, more power plants, more suppliers, all competing, which lowers costs and gives customers more access to choices. But we didn't quite achieve was giving those benefits to the small customers at the retail level. And that's really where community power comes in. It could be thought of as Deregulation 2.0 or really finishing the job of deregulation by giving our cities and towns access to competitive markets for energy services in a way that allows the small customers really to realize all of those benefits of competition and choice.

Laura Knoy:

So exchange listeners, we want to hear from you. We're talking about community power, how it works, what cities and towns are considering it. And later on, we'll examine some of the challenges. And we want to hear from you. What questions do you have about this? Is your community looking at community power?

Laura Knoy:

So Scott posted a comment on Facebook. He says, Are these communities looking for lower cost electricity, the same ones price-gouging utilities on their tax assessments for infrastructure to distribute and transmit power? Scott says towns can't have it both ways. Low electric rates and high taxes for utility infrastructure. Scott, thank you for writing in and Don, I'll throw that to you, please.

Donald Kreis:

I would say that those are separate issues. The point is well taken. I think a lot of communities with a lot of utility infrastructure within their communities have been overly aggressive on the theory that they're sticking it to the electric companies shareholders. In fact, property taxes paid by utilities are recoverable from customers. So when a town does that, it is basically taking money out of the pockets of its neighboring towns. And that is not a good idea. But community power functions at the competitive level. And I think that, first of all, as a factual matter, as far as I know, the towns that have been super interested in community power are not the same towns that are focused on seeing how far they can push the electric utilities in terms of extracting property tax revenue from them.

Laura Knoy:

Well, Scott, I appreciate the note. And speaking of the towns, Henry, do you have a list of towns and cities that are thinking about this, considering it? Who's involved in this?

Henry Herndon:

Oh, man. Laura, there are so many cities and towns across the state that are interested in community power. And I think we've really seen that in the some of the legislative shenanigans that are going on right now. Ten of the 11 mayors in the state signed a letter in support of community power that they sent to the statehouse. The Association of Counties weighed in. The Municipal Association weighed in. And then to get a little more concrete, there's sort of a core team that I've been working very closely with over the past year to research national best practices and chart a path forward that includes the city of Nashua, the city of Lebanon, the town of Hanover, Cheshire County. And I could go on and sort of a longer list of communities that either have committees or are exploring the possibility of getting on the pathway. There are several dozen from Warner to Harrisville Rye to Exeter to Bristol that are in some form or another beginning the pathway down towards community power. So I think there's a lot of excitement from all corners of the state.

Laura Knoy:

Ok, let's take a call. Gentlemen, this is James in Concord. Welcome, James. You're on the air. Go ahead.

Caller:

I was I was wondering, I run a I run a small farm and I invested in putting up a solar array. And since I'm a commercial entity, I have relatively low power consumption, but I get hit with this demand charge, which I consider sort of to be like a corporate tax. And I understand like why they have the demand charge. But I was wondering if you guys could talk a little bit about the demand charge and whether or not even something like that being levied against a small, low power consumer is hindering, you know, renewable energy. And so, you know, the kind of the payback for it.

Laura Knoy:

That's interesting. Yeah. And actually, James, I'm just curious, are you using your solar power on your farm or are you selling some back to the grid or what are you doing with that?

Caller:

Yes, I'm hooked in with net metering, and so I use it for my farm, yeah, and we still you know, I would say the demand charge is probably anywhere from 70 to 80 or 90 percent of our monthly bill.

Laura Knoy:

Wow, OK, good to hear from you. And Don, can you handle that question, please?

Donald Kreis:

Sure. Well, that's a question of rate design and it's terribly important. I think that demand charges are against my religion when it comes to residential customers, for exactly the reason that the caller just laid out, they're fundamentally unfair. And utilities like them because it discourages innovation and effective use of the electric grid and it administers the wrong price signals, meaning it doesn't encourage savings. Now, that said, demand charges are quite prevalent on the commercial and industrial side, and it's important that commercial and industrial customers pay their fair share of the electric grid. I would say that that particular customer on a small farm needs to take a look at how they are using electricity so that it can be smoothed out a little more and so that that customer can reduce his demand charges. Because if they're that high a percentage of his farm's electric bill, he could use some aggressive energy management efforts and a really robust community power aggregation program in his community would, I think, help him do that.

Laura Knoy:

At some point, though, and we don't want to get into every single last charged on on somebody's electric bill at some point. Utilities do need to make money to maintain, you know, the grid, the wires and poles and, you know, the meter at my house and so forth. I mean, those things need to be maintained. We all we all have learned that looking at Texas.

Donald Kreis:

Absolutely, and there's no question that utilities will continue to have a reasonable opportunity to earn an appropriate return on investment for their shareholders because there will always be distribution charges on your electric bill. Your electric utility has a monopoly on the distribution system, meaning the poles and the wires, high voltage and low voltage. And believe me, the utilities can and do make plenty of money doing that. Community power is talking about filling in essentially everything else, and there's lots of opportunity there as well.

Laura Knoy:

Well, thanks for calling, James, and good luck with the farm. And let's go to Norwich, Vermont, where Rick is on the line. Rick, you're on The Exchange. Welcome. Go ahead.

Caller:

So I'm curious about the you know, the let's refer to both wholesale and retail deregulation. Where would the incentive come for capital investment? Both for the robustness of the grid, vis a vis Texas, and also investments that wouldn't necessarily be realized in cost savings, but, for example, in reducing carbon footprint and that sort of thing.

Laura Knoy:

Two really good questions, Rick. Thank you, Henry. Go ahead.

Henry Herndon:

Yeah, I think it's a good question, but the we want to just distinguish between two things the utility will continue to maintain and operate the grid and be compensated for that. And that's an important role that the utility will play. One thing I do want to sort of circle back to, Laura, is you asked about how does this work in other states? And I just want to call attention to two models quickly that can sort of help illuminate some of this. And those two are the Massachusetts model and the California model. So in Massachusetts, aside from Cape Cod Light Compact, which Don noted, which is a good example, in Massachusetts, a lot of folks in this industry sort of think of it as Community Power 1.0 or the basic model. And it's superficial in a sense, because, you know, maybe you can swap out what kind of power you're buying and slap a green label on that and maybe get a headline for your politicians and maybe save folks a dollar or two a month. But there's not really systemic change in actual choice happening in the marketplace in Massachusetts, like some of the things, we have ambitions for it here in New Hampshire.

Henry Herndon:

And another model is the California model, which is not without imperfection, but in California, what we see community power doing is generating revenue for its cities and towns that they can then reinvest into local energy resources. So we see California community power driving innovation and driving investment into new renewables, like the caller mentioned in terms of decarbonization, energy storage, partnering with their utilities on micro grids and really building up resiliency as well at critical facilities, whether those be airports or hospitals. And we even see examples of communities in California partnering with urban planning and transportation planning to do bus fleets electrification and all kinds of really great, innovative things that all sort of tie together. So here in New Hampshire, we looked at Massachusetts, we looked at California. We said, what are the best practices and how can we apply those here in the state,to sort of leapfrog the more simplistic Massachusetts 1.0 and go right to the approach of community power that is going to make the most value for our cities and towns.

Laura Knoy:

Ok, let me make sure if I get this right, Henry, and this is going back to what we talked about earlier when we talked about goals. So the hope is if a lot of cities and towns jump in on this, they will be more interested perhaps in purchasing green energy than the traditional utilities. And so that pushes the move toward green energy faster than it's happening now. Is that what you're talking about there?

Henry Herndon:

It does, but there's two ways to think about it. So you can buy what's called a renewable energy certificate or a green label for your electricity. And that's all well and good. And maybe that's from New England or maybe that's from a Texas wind farm or something. But that's not really driving change because you're just buying the certificate that gets generated from some existing renewable energy somewhere else in the country. But the gold standard, what we really want to achieve, is building new local renewables for our communities that provide value directly to those communities. And that's really what I think the cities and towns in New Hampshire want to achieve. They don't want to greenwash their power with RECs or renewable energy credits. They want to see new local renewables constructed in New Hampshire or even in their communities that can benefit them directly. And that's what could be possible under community power.

Laura Knoy:

Ok, Rick, thank you for the call. So here's an email from Amy in Dover. Don, I'm going to throw this to you. Amy says, How can anyone advocate for deregulation and free market utilities when we are seeing in real time the devastating effects of these systems in Texas? Those residents that didn't lose power are facing charges in the thousands of dollars. Ask yourself how often you would be able to keep up with shopping around for your utilities in the midst of your already busy life. Amy says monopolies are bad, but deregulation is not the answer. Amy, thank you for writing. This is, as we said earlier, Don, a question on a lot of people's minds this morning.

Donald Kreis:

That is such an astute question. I just want to go back to the caller for a second from Norwich, Vermont, which is my former home town. So a shout out to Norwich. That caller asked about how can we encourage innovation and deployment of capital so that our energy grid evolves. I read the latest SEC filing that Everysource made, you know, their form 10K, which is basically their annual report. And, you know, they list the threats that they perceive to their future business success and right on page 18 of their form 10K. It says, and I quote, New technology and alternative energy sources could adversely affect our operations and financial results. So that tells me that legacy utilities, like Everysource, are afraid of change, just like the whale oil companies didn't survive the transition into electricity. I think our legacy utilities are appropriately freaked out about this wave of change that's coming. So Texas. Texas is not New England and the Texas electricity grid doesn't have the same wholesale price constraints that we have. Most importantly, there were retail suppliers in Texas apparently, who were simply exposing their retail customers to the wholesale price. So basically what they said to their customers was, and I'm guessing they did this in a not exactly transparent way, they manipulated customers into agreeing to a retail rate that would fluctuate in sync with the wholesale rate.

Donald Kreis:

And that's a disaster when your wholesale rate can go up to nine thousand dollars megawatt hour. That is that is ridiculously high. And you read horror stories of people getting electric bills in Texas that run into the tens of thousands of dollars. You know, you're talking about residential customers and small customers. That can't happen in New England. But, and this goes to many of the points that Henry has been making, what residential customers need is joint buying power. Right. You and I Laura Knoy or you and I, Henry, we don't have the clout in the retail marketplace or the wholesale marketplace to attract really good deals. But if I join with all of my neighbors in the city of Concord, the city of Concord's aggregation program will be able to go into the wholesale marketplace and get a good deal, that will protect me from some of the vicissitudes that arise when we have extreme weather events, which here in New England include the warm weather and the cold weather.

Laura Knoy:

Well, we keep talking about utilities, including Eversource. Coming up later in the show, we will be speaking with a representative from Eversource. Coming up in just a minute, though, we're going to go to Nashua, which is looking at adopting community power, the state's second largest city.

Laura Knoy:

This is The Exchange, I'm Laura Knoy. Today, what is community power and why is a small but growing group of cities and towns looking into this? So along with consumer advocate Don Kreis and Henry Herndon with the Community Power Coalition, we're joined now by Doria Brown, energy manager for Nashua. And Doria, welcome. So why does Nashua want to do this?

Doria Brown:

So Nashua wants to get into community power because we see this as an innovative option for our future. So Nashua has the largest renewable energy portfolio out of any community in New Hampshire, with our two hydroelectric facilities and community-held solar power. And we see this as an opportunity to decrease prices for our residents, as well as expand our renewable energy portfolio as privatized renewable energy is actually really hard to come by for the average citizen in Nashua.

Laura Knoy:

Your mayor has said that the community power program should, in his words, break social equity barriers. What's that about? Doria, how does community power help break social equity barriers?

Doria Brown:

So I was actually just getting into that, so that's an awesome question. This breaks social equity barriers, because it brings renewable energy to people who might not be able to afford it. So a solar array on a house might cost you 20 thousand dollars, but a community held solar array is something that everybody can access and everybody can get that renewable energy, so that we don't have those emissions going out into the environment.

Laura Knoy:

So it sounds like Doria, Nashua is not just interested in purchasing green power from elsewhere so that residents have, you know, that option, but becoming a creator or a provider of green power, is that right?

Doria Brown:

Yes. Now, she was already a provider of green power with our two hydroelectric facilities at Mine Falls and Jackson Falls. So we have renewable energy already and we are looking to expand that portfolio.

Laura Knoy:

Interesting. How will Nashua residents decide which power provider to choose if the city does offer community power? How do people sort of make the first step? I think there's some confusion around what does this mean for me? Who do I sign up with?

Doria Brown:

So the way that a community would make the first step is by not opting out of the community power program. So first, our community will start an aggregation committee, which will create an aggregation plan, and then that plan will figure out who our provider is for electricity. And we'll send out a mailer to all of our constituents saying, hey, we've chosen this provider for electricity and this is the price of the electricity. If you'd like to opt out of the program, you have opted out and you will stay on the Eversource deferred rate. And if you choose to stay in the program, you will be on the community power rate with that supplier. So it's not really about just shopping around. It's more about just choosing who your default supplier is.

Laura Knoy:

I see. So you pick A or B, it's not like you have to look at, you know, 16 plans and figure out what the best one is.

Doria Brown:

Exactly.

Laura Knoy:

So if this were to pass in Nashua, Doria, who would run it? Would it be You?

Doria Brown:

So it's a community-run program, so we would go through our legislative process with the Board of Aldermen to choose our provider and approve our aggregation plan. So it ultimately is a community decision.

Laura Knoy:

So do you have enough staff and technical expertize to to carry this out?

Doria Brown:

So that's where the Community Power Coalition comes into play. Nashua plans on joining the Community Power Coalition, where we will share back-office to service this program, so they will provide customer service, help us with our billing and rates, and bring us together with other communities to improve our buying power. So it will be a joint community effort when it comes to running the program.

Laura Knoy:

Yeah. Andrea, stay with us for a few minutes, please. I want to bring in Henry and Don. Henry, just your thoughts, listening to Doria describe what they're hoping to do in Nashua.

Henry Herndon:

Yeah, I think it's really exciting what Nashua is doing in Nashua's has been a real leader. And just a couple other details here on how this might look for the typical customer. So, say, Nashua Community Power. They make their plan. City council approves it. They join the Community Power Coalition, which has the technical experts to really manage the energy procurements and send the notifications to customers. What the customer might see is they'll get a notice in the mail, like Doria said, and that'll say, welcome to Nashua Community Power. Here's your price. Here's a little bit about our program. And what they could even do, is say, here's the baseline, here's the default Nashua Community Power price. But maybe here's an option. Maybe you want to opt up to a 100 percent renewable product and that might be at a little bit of a premium. But you can give your residents the choice to either take the cheaper default power, which could have a higher renewable content than, say, the state requirement, or that customer could also choose to potentially opt up to a higher green content or some other type of innovative products down the line as well. We talked a little bit about prices that fluctuate with time, time of use, rates, things of that nature. So those are just some other thoughts as well.

Laura Knoy:

And we've got an email from Bill in Warner who's skeptical that he might save more money. So, Don, I'll give this to you. Bill says, I wonder how much can really be saved. My current electric bill from Eversource shows a supply charge of thirty two dollars and a delivery charge of sixty one dollars. Even if I save 10 percent, it would be applied only to the supply charge. So I would likely only save three dollars and 20 cents. Even if the average supply charge is higher, it seems unlikely one would say much more than 60 dollars a year, hardly worth the effort. Bill, thank you so much for writing. There's a lot in that email, Don. Go ahead.

Donald Kreis:

Well, I think that if community power aggregation works as well as we hope it does, it will help customers use fewer kilowatt hours every month. And most of the charges on everybody's electric bill, are charges that are imposed per kilowatt hour. So that caller or that writer will save money not on the distribution charges and the transmission charges that he pays to Eversource, even though the community power aggregation program will be something he pays for through the energy service charge on on his bill. As I was listening to Doria talk from Nashua. And first of all, I agree with Henry that Nashua has really been a leader when it comes to energy innovation. I was thinking that when the legislature first adopted restructuring back in 1996, the idea is that the default energy service that is provided by the utilities would just be a backstop and most, if not all customers would migrate out to something in the competitive marketplace. And so when we have these municipal energy programs, that I think in effect in your city, like Nashua, becomes the default service. And the expectation is that almost all customers will want to be on that, because we know customers don't want to think about their energy choices all the time. They just want to flip their lights on and be done with it. And I think that these municipal aggregation programs have a better shot than the legacy utilities do, at managing their energy service in a way that is truly innovative and calculated to save customers a pile of money. So the point is well taken. You know, we're never going to be able to wipe out the distribution charges. The grid is an expensive thing to maintain, but I really do see these municipal programs as the best path that has been invented yet to really save residential customers some money and make them more powerful users of the grid.

Laura Knoy:

So, again, just to clarify, the distribution charge is the cost of managing the grid, Don. And that's not going to change.

Donald Kreis:

Right. Except insofar as you use fewer kilowatt hours of electricity every month. There is a fixed customer charge in everybody's bill. But most of our electric bills come through variable charges that we pay by the kilowatt hour. And I really think that municipal aggregation is going to help customers use fewer kilowatt hours. I do have to credit the utilities. They do manage our rate-payer funded energy efficiency programs. They do a very good job. But the utilities have no skin in that game. Their shareholders are not investing a dime in energy efficiency. That's all you and I, the electric customers in the state, and the natural gas customers.

Laura Knoy:

Doria, a couple more questions for you. Just from a basic customer perspective, who would customers communicate with, Doria, if Nashua were to adopt community power, when the power goes out or their meter is broken or they have a question about their bill?

Doria Brown:

So that is a very good question when the power goes out, you would be talking to Eversource because they would be managing our infrastructure. So that wouldn't change. When it comes to talking about your bill, you would reach out to the customer service group from the Community Power Coalition. So that would be the kilowatt-hour side of your bill. You would reach out to the Community Power Coalition if you wanted to talk about your rate. But if the power went out, it would still be the utility who is managing the the lines that bring energy to your house.

Laura Knoy:

How concerned are you, Doria, that utilities might have to raise distribution rates if they're making less money selling power? If Nashua takes takes over the the selling power aspect of this, how do they cover the costs of grid maintenance and security?

Doria Brown:

So distribution rates already cover grid maintenance and security and I think utilities will be making the same amount of money that they make now from distribution, as they've already stated, that they don't make much from power supply in the first place.

Donald Kreis:

They don't make anything - that's important. The power supply is totally neutral to their profits. They make no money on it. And as Doria just pointed out, the utilities will always be made whole for the cost of providing distribution service. That's just the way this works.

Laura Knoy:

There's a lot to wade through when it comes to electricity generation and distribution for sure. Jackie in Nottingham, emails to ask My house is served by the New Hampshire Electric Co-op. How is this similar or different from community power? Good question. Jackie, and Henry, can you jump in, please?

Henry Herndon:

It's a really good question because the New Hampshire Electric Co-op is unique in that it's it's already a democratic form of governance in the power sector, where it's cooperatively owned, and everyone who's a customer is is part of that cooperative ownership structure. And what community power is really trying to do is democratize energy down to the city or town level. So it's an interesting philosophical question. If you already have a democratic distribution utility, then can you layer in democratic city and town-level community power programs that integrate and work hand-in-hand with that utility company? And I think the electric cooperative deserves a lot of credit for really leading the state in some ways. They have electric vehicle promotion programs and electric vehicle charging, and they built a two megawatt solar array in Moultonborough. And they've really they've been innovators far, far more so than than Eversource has been. So it's a good question. And I think there's some good hopeful opportunities for partnership between city and town community power programs and the New Hampshire Electric Cooperative. But they've they've been doing some of the innovation on their own already.

Laura Knoy:

Doria. Last question for you, please. So where is the city of Nashua at in terms of putting this in place?

Doria Brown:

So we are at the point where we're joining the Community Power Coalition of New Hampshire and then we're going to start writing our aggregation plan and start up a program, hopefully by the end of the year. So that's kind of where we are.

Laura Knoy:

Well, it's been good to talk to you, thank you very much. That's Doria Brown, energy manager for the city of Nashua. So we've gotten a bunch of emails from people who live in cities and towns that are definitely looking at community power aggregation. Anne in Peterborough writes, She's working with Peterborough Energy Action, a grassroots organization working with the community to transition our entire town to 100 percent clean, affordable, renewable energy for all, and describes community power as an equitable way to provide renewable energy to every citizen, not just the wealthy who can afford solar panels and save money at the same time. Anne says she is worried about House Bill 315, which we'll talk about in just a moment. We got two emails from Keene, also people who are working on community power there. They say they are worried about House Bill 315. Peter is chair of Keene's Energy and Climate Committee, which just finished our plan, he says to transition to 100 percent renewable energy for electricity by 2030 and for thermal and transportation by 2050. Peter says Keene hopes to begin implementing that this summer. And then, Suzanne, also in Keene, she talks about Keene's plan for community power that will be ready to go as soon as PUC rules are issued implementing implementing the bipartisan bill Gov. Sununu signed in 2019. Suzanne also says House Bill 315 is derailing that process. So thanks, everybody, for writing. And coming up in just a moment, we will talk about House Bill 315 and we'll try and unpack it in a way that is understandable because it is complicated. We'll be back in just a moment.

Laura Knoy:

This is The Exchange I'm Laura Knoy. Today, what the community power movement is all about in New Hampshire and what it might mean for customers. We've been talking this hour with state consumer advocate Don Kries and Henry Herndon with the Community Power Coalition. With us now is William Hinkle, media relations manager for Eversource Energy. And William, welcome back to the show. Good to have you. So just real broadly, before we get into some of the details, please, William, what is the motivation, do you think, for this community power movement?

William Hinkle:

You know, Laura, I'd like to just start off by saying that, you know, we share at Eversource a lot of the same goals that have been discussed this morning. We don't have any interest in denying our customers benefits, such as lower cost or advancing clean energy or any of the other types of burgeoning innovation that are going to really define our clean energy future. But we do have a different perspective as a regulated utility that serves more than 200 New Hampshire communities. You know, there's nothing in law that currently prevents communities from pursuing the kinds of programs we've been talking about this morning. But those programs still have not rolled out or have been very slow to roll out. So it's been our hope with House Bill 315, which you referenced before the break, that we can streamline the regulatory process. So the aggregation piece of community power gets off the ground as quickly as possible, while the questions and concerns around other issues related to community power are fleshed out.

William Hinkle:

All of our guests, we've talked a lot about the energy service or energy supply, part of community power. We think that that can get off the ground right away. And we do recognize the potential that has to help our customers lower costs. And we do not make any money off of our customers energy supply when they see that item on their bill from us. It is a direct pass through to our customers that we do not profit on. So with House Bill 315, that part of it has been held up since the 2019 enabling legislation for community power. We've had a long process. I think people on on all sides of the issue realize that there have been some issues rolling these things out. And it is our hope that with House Bill 315, we can get that aggregation of energy supply running as quickly as possible while we flush everything else out through the regulatory process.

Laura Knoy:

And I am going to ask you about 315, because we got all those emails. But just want to ask you about the broader goal that I'm hearing here, William. The idea that communities are doing this because utilities have been too slow to adopt green power, how much do you think this interest, rising interest as Henry tells us, lots of cities and towns is a reaction to Eversource and others just kind of being sluggish on green energy.

William Hinkle:

Well, Laura, I think it's important for everyone to understand that when we purchase power on behalf of our customers, we are legally required to pursue the lowest rate possible for our customers, regardless of the type of fuel source. And that is one of the great advantages of aggregation at the community level. It allows local communities to pursue their own clean energy goals. And we think that that can move forward today and we are not opposed to that and we want we want to be a constructive part of that conversation.

Laura Knoy:

So let's get into House Bill 315, because, again, lots of people have been writing in on it and you mentioned it and our other guest mentioned it without getting too detailed. And I know that's difficult. William, what's the what are the changes that the House Bill 315 is seeking that, in your words, would streamline the process?

William Hinkle:

Well, so I think it's important that we separate out two things when we talk about community power. On the one hand, we've talked a lot about the aggregation piece or aggregating customers to procure energy supply. That piece has been allowed under New Hampshire law for quite some time. And we think that House Bill 315 will help that part of these programs move forward any quicker. What is being held up through the rulemaking process at the PUC are questions about everything else from what if one community wants to install certain different kind of smart meter that's not compatible with our system? There are billing issues, questions about data platforms and security, all of those things that are separate from the electric supply piece, where we are currently successfully running those programs in partnership with our communities in Massachusetts. House Bill 315 would align New Hampshire law with what is going on in Massachusetts. Henry referenced Massachusetts is a 1.0 version, that's kind of the way we see it. We can get the aggregation of supply off the ground so we can do the 1.0 as quickly as possible while we answer unresolved questions on everything else. And a lot of that does have to do with cost. And there were questions about cost earlier, and those are questions that we have, separate from the electric supply and the costs that go into those. The concerns we have are if a community pursues one of these programs and they choose to install a certain type of meter that isn't compatible with our systems, what do we do then? Do we go out and make our system accessible to that one meter and upgrade across the board, across the state, and then those costs get shifted to all the other communities we serve in the state? And similar type of questions on billing and other things. It's just those types of questions. If one community does something outside of the supply area, how do we make our systems compatible so it doesn't mess anything else up for our other communities and our services there, without raising costs? And those are the questions that we want to we want to answer through the regulatory process at the PUC. And it is our hope that with House Bill 315, we can move forward with aggregation while we resolve those other issues separately.

Laura Knoy:

So here's another question. This is a process question, William, but aren't these sorts of questions usually resolved in the PUC instead of a bill in the legislature? I'm just confused about that.

William Hinkle:

One of the issues was when the 2019 legislation was passed, there was a late amendment that had little to no opportunity for public input, which included utility input. And, you know, I don't think a lot of these questions were foreseen. And we've kind of seen gridlock at the PUC since then around all of these things because, you know, as a regulated utility that serves more than 200 communities in the state, these are the type of questions we have and the types of things we think about, that individual communities aren't necessarily always thinking about.

Laura Knoy:

Interesting. OK, so, Don, I going to bring you in talking about the PUC gridlock there, not allowing these sort of distribution and streamlining issues to be addressed, as William put it. What do you think, Don? What's your concern here?

Donald Kreis:

Ok, I got to get two things out before I say anything substantive in response to my friend William Hinkle. One, no day goes by without me having some interaction with Eversource. So I know that Eversource is an excellent company that has lots of excellent people in it who I enjoy very positive working relationships with. Two, it's important to keep in mind that Eversource is not the only electric utility in New Hampshire. We've already heard about the New Hampshire Electric Co-op. We also have Liberty Utilities. We also have UNITIL and it would behoove everybody to ask the other utilities whether they are as gung-ho about House Bill 315, which Eversource wrote, as Eversource is. Now, having said all of that, with all due respect to my friend William Hinkle, I really think there's a certain degree of, well, a word that starts with the letter B comes to mind. And I will use a euphemism for that word by just saying, Blarney. You know, there is a reason that the rulemaking has been hung up at the PUC, and that reason is Eversource, Eversource is not interested in allowing real change to take place. As Mr. Hinkle just confessed to you rather forthrightly, they're interested in making sure that aggregation is really just permission to municipalities to offer their load up to third party aggregation firms that are not really interested in innovation. They're just interested in making a little money as energy brokers. And what my friend Henry Herndon is talking about is a much more broad-based set of energy programs and initiatives. And that's exactly what Eversource is afraid of. They're afraid of losing their monopoly on meters. They're afraid that as innovation progresses, they will become less and less relevant.

Donald Kreis:

They consider this a potentially extinction level event. This could be like the asteroids coming in that are going to kill the dinosaurs. That worries Eversource. It should worry Eversource, but they should not be able to use House Bill 315 to thwart change. The other piece of this is, that Mr. Hinkle mentioned that community power aggregation has been authorized. That's true. It's been on the books since 1996. What changed two years ago is we authorized opt-out community aggregation. That is what makes community aggregation a feasible phenomenon for municipalities. And the idea that there was some sneaky late amendment that got in two years ago, that is not a tenable proposition. Governor Sununu had plenty of time to study the language of that bill in-depth. And believe me, he and his team did. So I just don't buy this idea that what we need to do now is to correct things that kind of snuck through the process.

Laura Knoy:

Is there a point, though, Don, about, you know, making things streamlined? I mean, customers speaking for myself. I don't want to think about anything. I just want to turn the lights on. So is there a point about, if communities are going to do this, there does need to be some connectivity, some streamlined aspect of it so that the power that a community, let's say Concord, that's where I live, purchases, is indeed able to effectively get to my house through the lines and wires that the utility may own.

Donald Kreis:

Well, so, Laura, the question is, you and I both want to just turn our lights on or off and get on with our day, right? We don't want to spend our day thinking about where our electricity is coming from. So the question really becomes who is the trusted oracle, who I want to basically turn those choices over to, so that they make them in my best interests. If you're fortunate enough to live in the electric co-op territory, you have an electric co-op that you're a part owner of. That's great. But if you're a customer at Eversource or one of the other investor-owned utilities, who do you want to trust? Do you want to trust a municipal aggregation program, a joint power authority like the one that we've been talking about, the Community Power Coalition of New Hampshire, or do you want to have to trust an investor-owned large utility, that's based out of state, like Eversource?

Laura Knoy:

So William, we want to let you jump back in, obviously, and you said House Bill 315 will streamline the process. We got four or five emails just before the break from people saying, no, no, this will actually derail the process toward community power. So what's what's your response to that, William, please?

William Hinkle:

You know, I think that the utility Eversource view has probably been a little sensationalized. And I think that probably leads to some of the concern you're hearing in those emails. There have been amendments in the work and we're open to compromise to make House Bill 315 workable for everyone. But there are very real questions about potential costs associated with the type of upgrades we're talking about beyond the aggregation of supply. And we think that those questions need to be answered for our customers, particularly those customers who live in communities that don't end up pursuing community power programs.

Laura Knoy:

Because, again, some communities may adopt this and some communities may not. Is that what you're saying, William?

William Hinkle:

Exactly.

Donald Kreis:

Well, there's a tipping point here, right? I mean, eventually more and more municipalities are going to feel, I guess, pressure, if you want to call it that, to do this and Eversource's default service could become irrelevant. That's what they're afraid of.

Laura Knoy:

Well, and last question for you, William Hinkle, because there is a hearing happening later today. So just remind listeners what's going to happen at that hearing, what you're hoping for.

William Hinkle:

Laura, we share the same goals as your other guests and everyone else involved on this issue, we want lower costs for our customers and we want New Hampshire to realize all the benefits that come with our clean energy future. Our hope is that we can move forward in a constructive way on House Bill 315 so that we can get aggregation off the ground as quickly as possible for our communities.

Laura Knoy:

Well, William, thank you for being with us. We really appreciate. We'll talk again. That's William Hinkle, media relations manager for Eversource and Henry, last question for you. So what are you keeping track of either in this bill, this hearing that's coming up, or as cities and towns start looking at this town meeting season is coming up and this will be on the docket in some towns.

Henry Herndon:

Yes, thank you for the question, Laura. So what are what are we keeping track of? Obviously, House Bill 315. It's an existential threat to community power. And that's something that we're keeping close track of, looking at what all the cities, how they're looking at moving forward in the state. But a couple of things I just want to boil down here in response to the discussion that's been going on. I was there and I was intimately involved in the regulatory process at the Public Utility Commission that unfolded over the past year.

Henry Herndon:

We had a series of stakeholder working groups with all of the utilities industry, cities and towns, regulators coming together. I facilitated many of those work groups and the folks on the community side bent over backwards to placate and compromise in terms of the foot dragging that we saw from Eversource in particular. So it's a little frustrating to hear this line about we're trying to streamline a regulatory process when in December I got an email from the regulators that said, the rules are done, we're ready to go, they're going to come out any week now. And then a bill gets put forward in this in the state house, sort of behind the backs of all those people who are working on the regulatory process that claims to then streamline the regulatory process when, in fact, it puts a freeze on it. So I'm looking at House Bill 315. And really, I think this is a story about all of New Hampshire from Governor Sununu and his leadership on down to the cities and towns that care about community power, that want to move this forward. And they have to come together and stand up against this bill, which really let's call a spade a spade, Eversource Monopoly Protection Act here.

Laura Knoy:

And we all have NHPR, we'll have people covering that hearing. I know we've been covering this story. In fact, reporter Daniela Allee helped us with today's show. We have to wrap it up there, gentlemen. Henry, thank you very much for being with us. And Don. Chris, thank you all for your time.Today's show was produced by exchange producer and NHPR news host Jessica Hunt, and as I said, with help from Daniela Allee. Thanks for being with us, everybody. This is The Exchange on NHPR.