Over the last two weeks, over sixty Afghans have arrived in New Hampshire, as part of the Biden administration’s rush to resettle over 70,000 Afghan evacuees by February 2022. One of the organizations helping them start their lives in Manchester is the International Institute of New England.

Here’s what arrival looks like.

Wednesday 8 p.m.

Sarah Niazi, an Afghan American case specialist and interpreter with the Institute gets alerts a few days (if not hours) before Afghan evacuees travel from U.S. military bases to New Hampshire.

A family of seven, with a week-old newborn, is expected on a flight tonight.

Niazi and Megan Clark, the Institute's community services manager, head to the Manchester airport. Niazi holds a sign that says “Welcome” in multiple languages.

The family never arrives.

Clark scans her phone for updates. It’s possible the family is still stuck at a military base, or that they got rerouted to another resettlement agency at the last minute.

Clark says she’ll be back in a few hours for another flight.

Wednesday 10 p.m.

Later that night, about 10 evacuees finally arrive. They wear name tags and carry plastic bags from a United Nations agency. One man leans on crutches. Another shows us a wound he got while serving with the Afghan special forces before he fled. He says he’s grateful his family got here alive.

Evacuees leave the airport and go to a hotel in Manchester, where Clark gives them dinner and some cash.

Tonight is the first time evacuees have had their own rooms and beds since fleeing their homes in Afghanistan in August. They’ll stay here for a few days or a few weeks while Institute staff and volunteers scramble to set up apartments in Manchester.

At 11:15 p.m., Clark gets a call from the agency coordinating resettlement. Another Afghan family has arrived at the airport and needs to be picked up.

Thursday 1:30 p.m.

The next day, Sarah Niazi arrives at the hotel to meet with evacuees and do a wellness check.

Afghans who fled during the U.S. military withdrawal and Taliban takeover aren’t technically considered refugees. Their path to permanent residency remains unclear, but for now, they’re eligible for certain government services. Refugee resettlement agencies are stepping in to help them get medical care, find jobs, enroll kids in school, and learn English.

Today, Niazi is focused on families’ immediate needs. Some left with barely anything; others are still trying to track down luggage that was lost en route.

The father of one family tells Niazi they left too quickly even to get their kids’ ID’s.

“I didn’t say goodbye to my father and mother,” he tells Niazi. “I didn’t say goodbye to any of my family. All I did was take my immediate family and leave.”

Niazi hands him a phone and tells him to download WhatsApp and Facebook to contact his family back home. They haven’t been in touch for over a month.

Thursday, 2:50 p.m.

Down the hallway, a man greets us in English. He agrees to speak to NHPR under a pseudonym. Like many evacuees, he’s worried the Taliban will monitor U.S. media and target his extended family back home.

For the last three months, Sami and his family were stuck at a U.S. military base, sleeping on cots and sharing quarters with about 10,000 others who had fled Afghanistan. They had no idea where their family would land in the U.S.; the process is up to refugee agencies and government officials.

[Read more of NHPR’s coverage on Afghan evacuee resettlement efforts here.]

Sami learned they were headed to New Hampshire just a few days ago.

“The first time I heard about the name [New Hampshire], I start searching through Google,” he says. “And in the Google map, it looks like a green place.”

Sami says when the Taliban took over in August, they got biometric data and other information on Afghans like him who had worked with the U.S. military. After several days of hiding, he embarked on what he calls a “deadly journey” from his home city to Kabul. On the bus ride to a safe house with his family, he wore a burka to hide his identity.

The Taliban stopped the bus and began checking every passenger. Sami says he was sitting in the very back. The Taliban had almost gotten to his seat when something happened outside and they got off the bus.

“If he got to me, definitely he would have killed me” he says.

Now that he is in the U.S., Sami is trying to stay in touch with his brother back home.

“Every day when he sends me messages, he says no one is feeling safe. Everyone wants to get food,” he says. “There is not enough food for all the people.”

Sami is one of thousands of Afghans who had already begun applying for a special immigrant visa (SIV) prior to the U.S. withdrawal. The visa is available to Afghans who helped the U.S. government, but the process slowed during the Trump administration and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sami says he originally applied at the urging of his wife. They were worried for their kids’ safety and future.

“I just want for my kids to be in school, to learn,” he says. “That is my really big hope.”

Thursday 4:15 p.m.

As the sun creeps towards the horizon, Sami’s family stands outside the hotel with other relocated Afghans. Their kids eat chips and giggle. One asks me for a soccer ball.

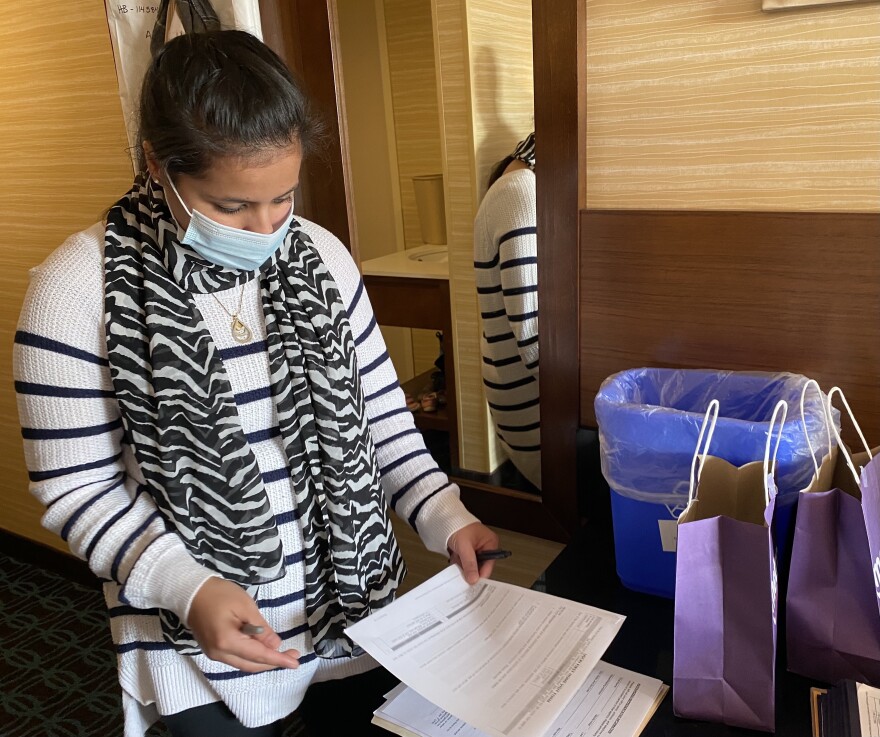

Sarah Niazi emerges from the hotel with a big stack of papers. She has just spent the last hour teaching a pair of cousins how to use Facebook to contact their family.

“It’s been a very long day,” she smiles.

Despite the hurdles ahead, Niazi says she feels a sense of purpose. Many of her family are still in hiding in Afghanistan. She’s made calls to government officials and the U.S. State Department. So far, no word. For now, Niazi is glad there are people in Manchester she can help.

“I couldn’t help anyone back home,” she says. “But I’m here and I’m able to help them try to resettle the best way that I can.”

Until now, there have only been a handful of Afghan families living in New Hampshire. Niazi says some evacuees didn’t expect anyone here to speak their language. Meeting her, they’ve told her, makes them feel a little more at home.