Each week in Manchester, in an undisclosed location, a similar scene unfolds. On this particular day, in early September, it goes like this: A few people set up a card table in a shady spot. In front of the table they place a few plastic buckets.

Soon, a woman approaches holding a shopping bag. Inside are several used syringes. She empties the bag into one of the buckets, chats with the people manning the table, then refills the bag with a few boxes of clean syringes.

“I just dropped off I think 20,” says the woman, who declined to give her name because she’s using injection drugs. “And I think I got 30.”

Over the next few hours, this simple transaction repeats itself dozens of times: People hand over dirty syringes in exchange for clean needles. This is the Queen City Exchange, the only syringe service, or needle exchange, operating in New Hampshire’s largest city.

But it would be easy to walk past the exchange and never know what was happening. There are no visible signs advertising clean needles, no uniforms for the volunteers staffing the tables. The time and location of these weekly outreach sites are shared only by word of mouth.

“We try to keep it pretty private,” said Kerry Nolte, who works for the New Hampshire Harm Reduction Coalition, which helps run the Queen City Exchange. “Broadcasting a location or where we’re going to have outreach may deter some people from coming.”

Nolte, in fact, is so worried about possible public backlash, she wouldn’t allow NHPR to visit their outreach site unless we agreed not to share its exact location.

Notle’s concern underscores a simple fact: While New Hampshire is among the states hardest hit by the opioid crisis, it’s been much slower than other parts of the country in adopting syringe services.

That's despite decades of research that shows they save lives and money. They limit the spread of Hepatitis C and HIV. They make cities cleaner and safer by collecting dirty needles that would otherwise end up on the ground. One study compared two cities and found that the city with a syringe service had 86% fewer needles on parks and sidewalks.

People using drugs who visit syringe services are five times as likely to get addiction treatment and three times as likely to stop using drugs altogether. Syringe services can reduce overdose deaths by distributing the overdose reversal drug, naloxone. Many also offer HIV and hepatitis C tests, referrals to addiction treatment providers, and even condoms. Studies also show they do not increase crime.

For these reasons, syringe services were long ago adopted in some other parts of the country as a useful public health tool. New Hampshire’s neighboring states, for instance, have all had syringe services since the 1990s. But, two years since they were legalized here, syringe services are struggling to get off the ground.

The reasons are many, ranging from state policy to local skepticism. And the delay has been particularly pronounced in Manchester, a city often seen as the center of the state’s opioid crisis.

State Policy

Andrew Warner is one of the volunteers working with the Queen City Exchange. He has also has worked at syringe service in Massachusetts.

He can spot a pretty obvious difference.

At the Massachusetts syringe service Warner was a paid staffer. His salary and all the materials for the syringe service were paid for by the state government.

In New Hampshire, syringe services receive no state funding. The state law that legalized syringe services in 2017 stipulates that they must be “self-funded.”

That language has raised questions in the past about whether the state is even allowed to funnel federal dollars to syringe services. Even if federal money was to reach syringe services in New Hampshire, federal rules require that the money cannot be used to buy syringes.

Without money from the state or federal government, groups like the Queen City Exchange are forced to rely on grants, donations, and volunteers like Warner.

“So we’re trying to find grants for private money to do this when a 40-minute drive away, the department of health in Cambridge (Massachusetts) is paying not only for us to do the work but then also for all those things,” said Warner.

Still, syringe services have been able to take root in some New Hampshire communities. In 2018, about 280,000 clean needles were distributed by syringe services in New Hampshire. That might seem like a lot, but in Maine 760,000 syringes were distributed in 2018, and in Vermont that number was more than 1.2 million.

Local Challenges

There are five syringe service programs currently operating in New Hampshire. The largest are on the Seacoast and in Nashua.

Manchester, arguably the city with the greatest need, didn’t have one until April of this year.

But even though the Queen City Exchange is now operating in the city, Nolte says they have a long way to go.

“What we’re doing now is really a drop in the bucket of what the needs are.”

Between April and July, the Queen City Exchange distributed only about 7,000 syringes in Manchester. In Burlington, Vermont – which has less than half the population of Manchester – the local syringe service routinely distributes more than 500,000 clean needles a year.

Nolte says it will take time for word to spread and trust to be built within Manchester’s drug-use community.

But the program also faces skepticism from Manchester city officials. In internal emails obtained by NHPR through a Right-to-Know request, city officials expressed frustration that the Queen City Exchange began operating without getting the backing of other community groups.

Public Health Director Anna Thomas was one of those officials. She says her concerns are rooted in a lack of oversight for syringe services in New Hampshire.

“It’s hard to see these things roll out in communities when we don’t know if they are practicing to the fidelity that is prescribed in evidence-based practices,” said Thomas.

Thomas worries about volunteers not being properly trained to run a syringe service.

“A lot of things could go wrong,” said Thomas. “You’re dealing with individuals who are actively using… When you’re putting people out in the field like that, these could be very hazardous environments for staff.”

Asked if she had any problems with the Queen City Exchange operating in the city, Thomas was lukewarm.

“They can do what they want to do,” said Thomas. “I have no basis to say they should or shouldn’t.”

Thomas says ultimately she’d like to see the city health department collaborate with community partners on its own syringe service. But at this point, those plans are not definite.

In the meantime, that leaves the Queen City Exchange as one of the only ways to get clean syringes in Manchester.

One person who received syringes at the Queen City Exchange and didn’t want to be identified was blunt when asked how difficult it is to get clean syringes in Manchester right now.

“Without these guys? It’s impossible.”

Pharmacy Access

Public policy is one obstacle to a more robust network of syringe services in New Hampshire. But the shortage of sterile syringes here is also driven in part by the fact that many pharmacies refuse to sell them to customers without prescriptions.

Since 2001, state law has allowed pharmacies in New Hampshire to sell syringes to customers without prescriptions. Increasing syringe access through pharmacies can have similar public health similar public health benefits to syringe services.

“The problem is you don’t see a lot of pharmacists actively participating in that,” says Michael Bullek, head of the New Hampshire Board of Pharmacy.

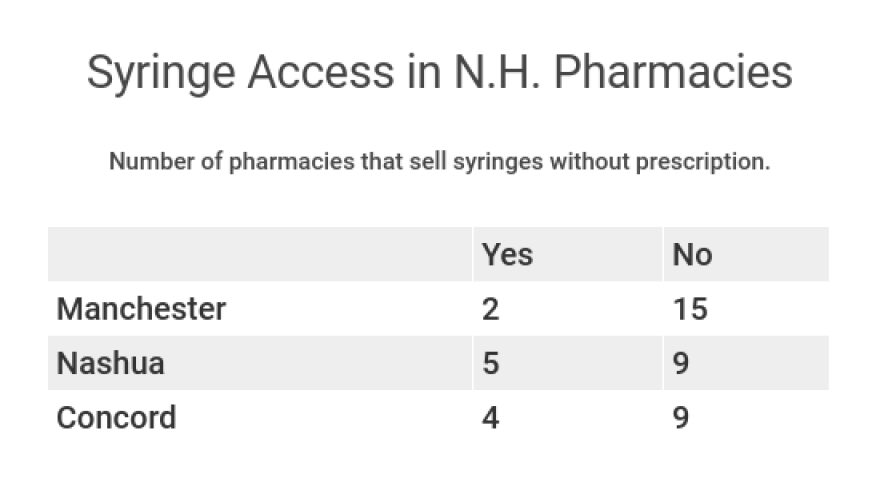

At least 17 pharmacies operate in Manchester. Only two of them sell syringes without prescriptions. It’s a similar story in other parts of the state, though not as stark as in Manchester. Five of Nashua’s 14 pharmacies sell syringes without a prescription, for instance.

Bullek says some pharmacists are concerned about finding discarded needles in store bathrooms or in the parking lot. He says others have more fundamental objections about enabling drug use.

Bullek says the New Hampshire Board of Pharmacy doesn’t have an official position on whether pharmacies should be selling syringes without prescriptions. But the group did recently include a message in its monthly newsletter, reminding pharmacists of the benefits of syringe access and of the relevant state laws.

Still, Bullek says more could be done. He suggests the state could play a larger role in educating pharmacists about the benefits of syringe access.

“I think the education needs to be more than me sending out a board notice stating that this is available.”

‘A Slow Process’

Back in Manchester, Queen City Exchange volunteer Andrew Warner draws on his own experience as a former drug-user when speaking to people picking up syringes.

“I try to treat people the way that I wanted to be treated back then. Or how would I want someone to treat my brother or sister if they were in that situation,” said Warner.

Warner said the group is just now beginning to build relationships with users in the city. Relationships that he hopes will eventually lead to treatment.

“We have to keep these people alive until they get to the point where they can make these decisions that are beneficial for them,” said Warner. “It’s a slow process.”

In the meantime, Warner said the fact that he’s beginning to see the same people come back each week is a promising sign.

“They’re alive,” he says.

At this point, Warner says, everything feels like a small victory.