Many Granite State electric customers are scratching their heads after an electricity supplier, Power New England, was abruptly kicked out of the market two weeks ago. Customers of Power New England and its sister company, Resident Power, have had to try to sort out what's going on from media reports where utilities and power suppliers are slinging accusations back forth indiscriminately.

So here’s a breakdown of what has happened to date.

Who are Resident Power and Power New England?

Let’s start with the basics. Deregulation has allowed for new companies to sprout up that buy power from whoever is selling it cheapest. There are two types of companies involved in this market: aggregators and suppliers.

Aggregators gather up customers and deliver them to an electric supplier. They essentially like a mortgage or insurance broker, and do no actual buying or selling of power. The NH PUC, which regulates these things, lists 80 registered aggregators.

Suppliers have to get over a much higher bar, and there are currently only 14 registered with the state. They actually buy energy, though they do not own the power lines or utility poles. One of the state’s four utilities – PSNH, Unitil, the New Hampshire Electric Coop, and Liberty Utilities – actually deliver the energy.

Resident Power is an aggregator and PNE is a supplier. They were the first companies to break into the residential electric market in New Hampshire, around two years ago. A father and son team of industry veterans runs them. Bart Fromuth is the son and Managing Director of Resident Power and his dad Gus Fromuth runs PNE. Gus was deeply involved in bringing deregulation to New England in the 90s.

The boundaries between the two companies are somewhat fuzzy. Bart Fromuth says the companies were designed to work together from the outset, “They certainly have common ownership,” he says, “but again I do want to make a point that PNE was backstop in terms of being able to supply customers.” In other words, when Resident Power started, there were no competitive suppliers who would take residential customers, so the Fromuths started their own.

What Happened to PNE?

The best way to operate a competitive electric supplier has perhaps not been established as of yet.

PNE’s business model meant leaving itself exposed to greater risk. PNE bought electric contracts for batches of around 700 customers at a time. And it was buying the electricity to supply those customers on the open market, while it worked up enough to form a batch. Waiting until a batch was formed to buy a contract helped PNE get a lower price by buying in bulk, but it was a bigger risk too.

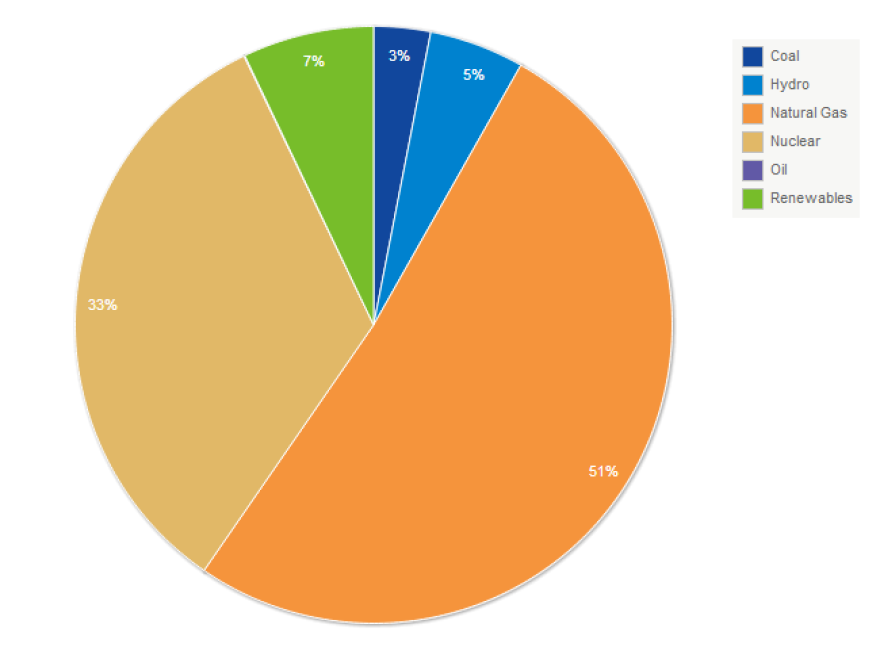

Then, when winter cold snaps came, electricity prices spiked. This is because more and more New England residents and electricity power plants have been converting to natural gas. So when it gets cold people heating their homes and power plants are suddenly competing for gas. Combine this with a natural gas pipeline network that hasn’t grown at the same pace as demand, and the stage is set for a big price jump.

As the first competitor against the big utilities in the state, it was in uncharted water for PNE, and when the price leapt it found itself in a whirlpool.

“PNE was receiving receivables from a very mild December, but they’re paying out five and six times that for the end of January into February,” says Bart Fromuth.

PNE was getting paid for the previous months when prices were low, and buying at a much higher price. Because of that lag, they burned through their cash-on-hand too quickly. Once they couldn’t pay their bills, the operator of the Grid, the New England Independent System Operator (ISO-NE) booted them out of the market.

PNE’s competitors, Electricity New Hampshire (ENH) and North American Power say they don’t operate in this way, so they don’t suffer as much from drastic fuel price swings.

The owner of ENH Kevin Dean says this is the kind of thing customers looking for a new supplier should ask about. “We put together enough financial resources to take every home in New Hampshire, and we buy for that contract,” says Dean, “That’s one of the most important things that a customer of any supplier should ask when they’re contemplating enrolling.”

How is Fairpoint Energy Involved?

Fairpoint has branched out from just providing communication services, into becoming an energy supplier. This arm of the business is called Fairpoint Energy.

As PNE’s finances were unraveling, but before they were ejected from the market, Resident Power worked out a deal to move its customers to Fairpoint. In their role as utility, PSNH would be in charge of making the switch. As per PUC rules the switch would happen at the next meter read for each customer.

That was happening at a rate of about 300 to 400 hundred customers a day. The Fromuths knew that PNE’s ejection from the market was imminent, and wanted this to be sped up to get all 8,600 of its customers to Fairpoint. Also, per PUC rules, they asked PSNH to do “off-cycle meter reads” so that could happen. According to Gus Fromuth, they even offered to pay PSNH for the man-hours it would take to do that.

They are keen to switch those customers to Fairpoint, because it allows Resident Power to continue acting as the aggregator for these customers and making money as a middle-man.

PSNH declined to do any off-cycle reads. The PUC rules say that utilities can deny such a request if it is not given a five-day, “proper notice”. From documents filed at the PUC it’s not clear what day Resident Power made the request for the off-cycle reads, but the paper-work to move the customers was filed February 8th, and the ISO market suspension came on February 14th.

When PNE got into trouble, around 7,300 customers who hadn’t yet been moved were automatically switched to PSNH, with its higher electric rates.

Context for the Blame Game

In the scrum that followed, PNE and PSNH have hurled accusations back and forth. PNE is trying to portray PSNH as obstructing free-market competition, saying it was too slow in moving customers to Fairpoint. “We offered every inducement in the book to get them to do that, and I find it very, very bewildering that they didn’t do it,” says Gus Fromuth.

For its part PSNH says it simply couldn’t move customers over fast enough, and has been aggressively framing this as a teachable moment. “PNE, they engaged in some risky behavior, they gambled on the energy market and they lost,” says PSNH spokesman Martin Murray, who goes on to say that this is a good opportunity for the PUC to look into some shady marketing that the competitive suppliers have been

engaging in.

To understand the rancor flying back and forth between these companies and PSNH, it’s important to remember that the little guys aren’t the only ones facing an uncertain future. Ever since the market was opened to competition, PSNH has been losing customers hand over fist. Upwards of 80 percent of large commercial and industrial, 21 percent of small commercial, and now 7 percent of residential customers have chosen a new supplier.

Now that the first companies to crack open the residential market are struggling, it’s no surprise that PSNH has been vocal, pushing this story to the media. They are trying to staunch the flow of residential customers jumping ship.

Many industry watchers say that PSNH’s high rates are tied to owning and operating a fleet of coal and oil fired power plants that at current fuel prices are more expensive to run than market rates.

“It’s a recipe for disaster,” says Howard Moffett an industry attorney in New Hampshire.

He says those watching know that PSNH is fighting to hold on to customers. If more customers leave the cost of PSNH’s power plants will be spread across fewer and fewer bills, causing their rates to become ever more uncompetitive. So if the price of natural gas stays low, PSNH may eventually have to get rid of its power plants.

“Whether or not PSNH will choose that option before it’s forced into a bankruptcy or some other draconian thing like that, that’s up to PSNH,” says Moffett.

PSNH asserts that these plants are an important hedge against the price volatility of Natural Gas, which this incident has put center stage. Indeed, PSNH’s Martin Murray recently told the Union Leader that thanks to this winter’s high electric rates the largest boiler at their coal fired Merrimack Station in Bow “has been running every day of 2013,” a sign that at least this winter, PSNH’s plants have been competitive enough to sell into the market.

How long this will last is another question. Plans are in the works to expand the natural gas pipelines coming into New Hampshire, but they won’t be completed anytime soon. “The pipeline is not supposed to go online until 2016,” says Taff Chandler Senior vice president of North American Power, another PSNH competitor.

As more homes convert to gas heating, it’s an open question if big price swings in electricity will become the norm in New England winters for the next few years.

What’s Next for PNE and PSNH?

These are all questions that regulators are looking to sort out.

The Public Utilities Commission is taking up an investigation of whether it makes sense for PSNH to own its power plants in current market conditions.

And Resident Power and PNE have been called before the Public Utilities Commission to explain how closely together their businesses are tied, and why they haven’t been particularly transparent in communications with customers.

These two companies are definitely in the hot-seat, and their future is at stake. While PNE can return to the ISO-NE market once it builds up enough capital to buy back in, the damage to its reputation might be too great to make that comeback, at least in the near term. And that’s not even considering the penalties that the PUC could decide to levy, a question that the regulators will take up March 20th and 22nd.