Jeanne Sokolowski never encountered a "frost heave" before she moved to New Hampshire. The erratic spring road bumps are common here. More of a nuisance than a curiosity for most. But for Sokolowski, it wasn't just the unfamiliar topography.

The proliferation of road signs - FROST HEAVES, in blaze orange - struck her as unique. And she wasn't alone.

"I posted a photo of one of these signs (on Facebook) and my friends and family from the Midwest and elsewhere chimed in, saying how unusual that was," she says.

She turned to NHPR's "Only in NH" series to get to the bottom of it. She asks, "How and when did the term 'frost heaves' originate? Is the phenomenon unique to New Hampshire?"

Sokolowski moved here from Minnesota. She didn't recall experiencing frost heaves there. The Minnesota Department of Transportation confirmed her recollection. They aren't a big issue there.

The first part of her question is a little trickier to answer. In fact, while New Hampshire's erstwhile resident poet Robert Frost describes frost heaves in the first lines of his classic 1914 poem, "Mending Wall," he doesn't call them by name. In 1914, Frost wasn't using the term "frost heave." So how did it come about?

The answer might lie in a collection of scientific papers titled, "Historical Perspectives in Frost Heaves Research," published in 1991 by the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory in Hanover, N.H. the papers trace the historical study of frost heaves, pointing to a 1694 Swedish geologist and chemist, Urban Hiarne, as an early observer of the phenomenon. In his beautifully calligraphed manuscript, Hiarne describes the "earth casting" and "earth shooting."

Throughout the following centuries, scientists and poets described underground ice lenses and the "earth-slide phenomenon," but according to these papers, it wasn't well-studied until the 20th Century, perhaps in part for two reasons.

First, tree roots help mitigate frost heaves. As settlers cleared the New England forests, frost heaves would have grown more common, disrupting stonewalls and pushing underground boulders up into pastures.

Second, around the time that Robert Frost wrote "Mending Wall," highway research was beginning in earnest with the rise of automobiles and paved roads. In 1915, Good Roads magazine, one of many new highway research journals cropping up, made reference to "frost action" and noted its deleterious effects on concrete roads. Meanwhile, geologist Stephen Taber had just begun his research in South Carolina. In 1929, he published the definitive paper, "Frost Heaving," which laid the foundation for understanding the mechanisms behind them.

After that, it appears the name stuck.

As for the second part of Sokolowski's question - are frost heaves unique to New Hampshire? - the answer seems simple: No.

"It's associated with New Hampshire but not exclusive to New Hampshire," says Bill Boynton, long-time spokesman for the New Hampshire Department of Transportation.

As for the bright, orange signs, DOT estimates they post over a thousand a year. But New Hampshire is not the only state to do so. Vermont posts signs for frost heaves, as well as more general warnings, "BUMP."

Frost heaves occur in cold regions around the globe. They've been observed not only across New England, but also in Scandinavia, Russia, Canada, and even on Mars - the Phoenix rover landed on an extraterrestrial frost heave in 2008.

But could New Hampshire have an unusual number of them? There might be a few reasons to think so.

"I have some photos of frost heaves you would not believe," Malcolm "Tink" Taylor says. He's a former state legislator from Holderness. He serves on local and state transportation committees and he's stoked a lifelong interest in roads. When he sees a frost heave, he gets out of his car and takes a picture for his own records.

"When you get into New Hampshire and into Vermont, you've got these craggy old mountains and exposed ledge, and you've got a lot of subterranean water sources," Taylor explains. "We've got a lot of water in New Hampshire, and a lot of it is traveling underground, and that's what's contributing to the heaving. I think the lay of the land has a lot to say about it.

Taylor adds that some of New Hampshire's roads are centuries-old. Some were built originally for foot traffic and stage coaches. They weren't built to the specifications of modern highways, with a foundation of permeable gravel and good drainage to prevent underground moisture.

But building a durable road from the "bottom up," as Taylor puts it, is expensive.

"You can spend $50,000 to $100,000 to resurface or repave a road and keep it in good condition," Boynton says. "Once it fails, you're looking at $1 million a mile in order to rebuild a road, and in some cases even more."

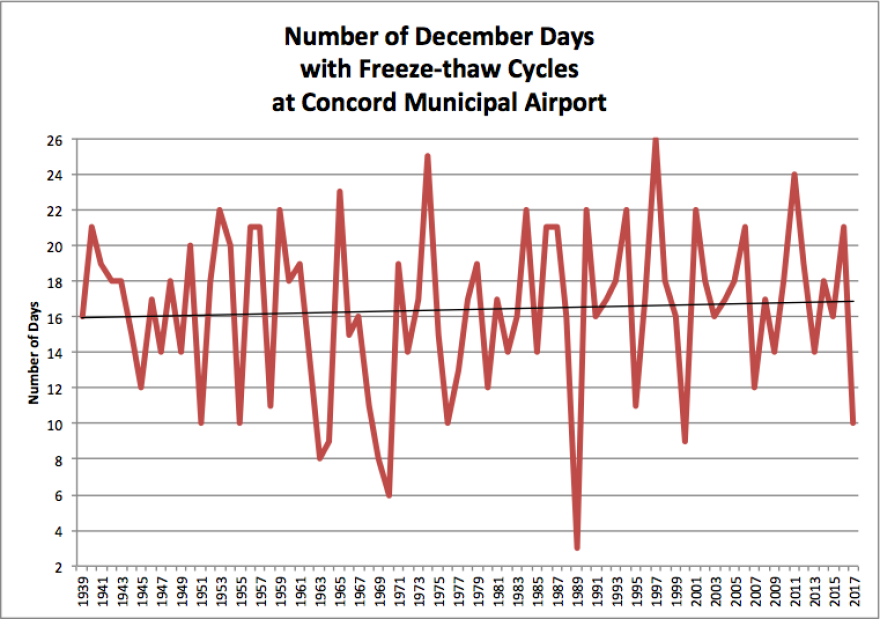

New Hampshire's volatile freeze-thaw cycle might be another factor.

"Why does New Hampshire have so many? It gets back to that fluctuating around the freezing degree mark. I grew up in northern Maine and it wasn't unusual to be 20 below for weeks at a time," Boynton says. "If it's frozen all the time, then you're less likely to get his phenomena."

The combination of moody New England temperatures, old roads, craggy geology, and highway costs all suggest a certain inevitability when it comes to frost heaves. But saying that is one thing - living with it is another.

Don Brown knows that as well as anyone. He runs the Corner House Inn, a restaurant and pub in Center Sandwich. It's a cozy spot with a hint of the up-scale. To get there, you typically have to drive down Route 113, a hilly, winding, and often frost-heave-ridden country road. The journey isn't too bumpy now. But in 2014, it was in tough shape.

"Any time you ran into virtually anyone, whether it was at the post office, the coffee shop, that was what everyone was talking about," Brown says. "I used to refer to it as similar to mogul skiing, because you had to drive around all these big frost heaves just like you were going down a course."

Brown's been running the Corner House for 37 years, so he's no stranger to New England seasons. But this was different.

"Usually, frost heaves appear around February and they last for a month or so and then they eventually go away as the ground thaws," he says. "What had happened was, the roads had taken such a beating over the years and were lacking the necessary maintenance, so those frost heave conditions lasted year round."

Brown's restaurant, like a lot of businesses in the Lakes Region, is seasonal. He relies on the extra revenue from summer visitors. When customers started remarking on the bumpy roads in July, he got worried.

"They just couldn't believe it. They'd say, 'oh my gosh, what's going on with your roads? We're not coming back because it's just beating up our cars too much.'"

Since then, Brown says, the NHDOT has fixed up some of the roads in the area. But not in that "bottom-up" long-term way. The roads might be in better shape now, but it's hard to know how long that will last.

As for Jeanne Sokolowski's question, even though they might occur around the world and beyond, part of living in New Hampshire means living with the frost heaves.