If you follow New Hampshire politics, you’re probably familiar with the ritual of the midnight vote, where a handful of tiny, mostly rural towns stay up late to cast their ballots as soon as election day dawns.

And you would be forgiven for thinking all the credit for this tradition goes to Neil Tillotson, the bespectacled businessman who was so well known as the face of Dixville Notch’s nocturnal vote that he’s honored with his very own bobblehead at the New Hampshire Historical Society gift shop, complete with a ballot box and all.

But New Hampshire’s midnight voting tradition didn’t actually start in Dixville — or with Tillotson. Instead, according to the earliest public record we could find, it started a few miles away, and a few decades earlier, with a 27-year-old woman named Genevieve Nadig.

This story is part of NHPR's ongoing series, "Unsung," exploring the stories of New Hampshire women (past and present) we think we know, and those we don't.

Heading into the 1936 election, New Ashford, Mass. — a small community nestled in the Berkshires — thought its reigning role as the country’s leading voting precinct was secure. According to the local paper, the Berkshire Eagle, “from 1916 to 1932, for five presidential elections, New Ashford set the national record for being the first electoral unit to report her election returns.”

But about 200 miles north, the people of Millsfield, N.H., had another idea. What if they opened their polls even earlier — as early as possible on election day? Right at midnight.

The citizens of New Ashford, needless to say, were not pleased.

“They had paid no homage to the precept of early to bed and early to rise,” the Berkshire Eagle later wrote of Millsfield’s stunt. “Here was sheer exhibitionism. Here were seekers after notoriety.”

But the rest of the press didn't seem quite so concerned with notoriety. A new tradition was born.

“It was the first time in history that the American public has been able to read any election returns in the morning newspapers of Election Day,” the Boston Globe reported. “In fact, because of the difference in time, the news reached California and other far western states on the night before Election Day.”

And all the credit for launching the tradition went to one woman: a 27-year-old who was known for painting scenery and selling balsam fir pillows from her family’s garage. Her name was Genevieve Nadig.

Rick Nadig, Genevieve’s great-nephew, lives in Errol and runs the Black Bear Tavern in Colebrook; he drives past the family home where the midnight vote began almost every day.

The idea to vote at midnight, according to family lore, was a team effort between Genevieve and her father, Henry Nadig. By 1936, the family was already active in civic life: Henry, a prominent local doctor, led a campaign to get Millsfield its own voting privileges a few years before.

“I would guess it was because, you know, they wanted to be involved and have a voice and have a say in really what went on,” Rick says. “Because what goes on in Concord sometimes doesn't necessarily fit in what happens up in the North Country. We’re always last. And I think they knew that.”

While the idea for the midnight vote might have been a collaboration, records from the day of the vote say Genevieve was the one who did all the work to pull it off. Her dad was out of town at the time of the election and voted by absentee ballot.

According to the Boston Globe, Genevieve converted her “garage shop studio as the polling place,” posting a town warrant and voter checklist on the front door.

“She improvised a booth of canvas, draped around a space in which the voter, seated on a soap box, would mark his ballot on the flat top of a sewing machine,” the Globe wrote. She invited her neighbors to come over for sandwiches, coffee and cookies a little before midnight. While five of them declined, five others showed up — but by that time, so did plenty of press.

“The telephone began to ring frantically,” the Globe’s story continued. “News services from New York called up. Boston newspapers called up. A magazine called up. The telephone operator at Errol, next town down the road, lost her sleep.”

Eventually, the Globe reported, the crowd grew so large it necessitated a change in the location of the ballot room: The event moved from the garage into the main house, where “guests and visitors sat in the front room of the old farmhouse, looking at the genuine Currier and Ives prints on the walls, while the voters went into the dining room.”

And over the years, Rick Nadig says Millsfield’s vote remained something of a media spectacle — and a headache for local telephone operators.

“They would climb the telephone poles back in the day and cut the lines because each one wanted to be the first one to get it in, get the report in,” he recalled.

Some people might balk at the idea of welcoming crowds of strangers into their homes every four years for the election. But not Genevieve.

“Til the day she died, [she was] very spunky and outgoing,” Rick says. “She enjoyed stories. She enjoyed meeting people and really, you know, learning about people.”

Before she moved back to her family’s farm in Millsfield to take care of her grandfather, Genevieve had been, according to her alma mater, “living a very busy life.”

“She has in the past few years been studying Art in both New Haven and New York. Last summer she managed a Tea Room and Gift Shop,” read her entry in the alumni section of the 1929 Gray Court School yearbook. “This winter she has been painting New Hampshire landscapes and this summer expects to open a Studio near the Dixville Notch.”

After settling down in New Hampshire, she married a logger, Elmer Annis, and took his last name; that’s why later news reports about the midnight vote describe a celebration at the home of “Genevieve Annis.”

She embraced the outdoors in Millsfield, riding horses and — later — snowmobiles, according to her family. But she also kept on painting, sketching, writing poetry, practicing foreign languages and reminiscing about her days in design school.

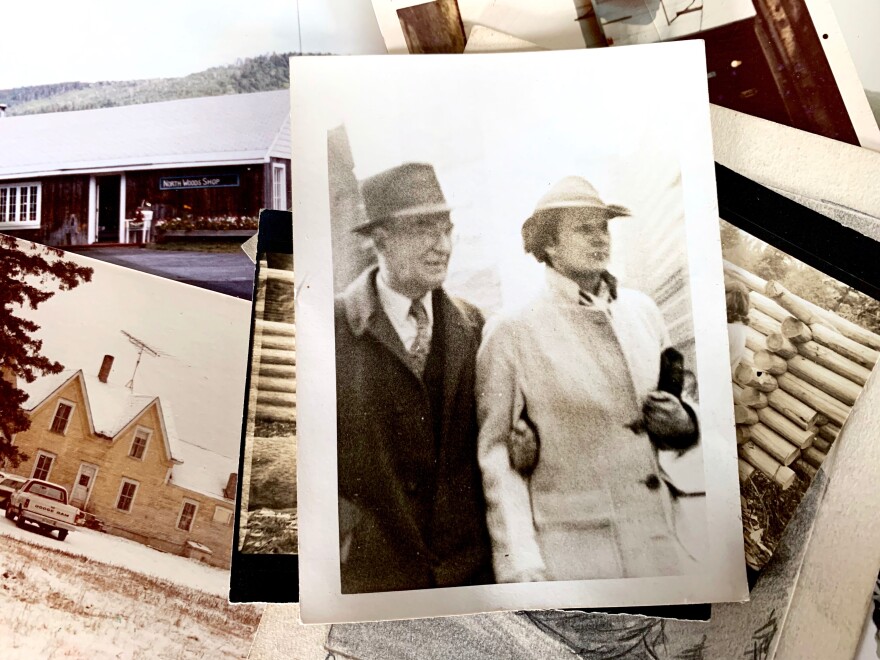

She was a faithful Republican who delighted in meeting Presidents Nixon and Reagan. Clifford K. Berryman, a famous political cartoonist for The Washington Evening Star, was so enamored after visiting Genevieve he sent her a personalized drawing depicting two stuffed pillows he picked up from her roadside gift shop. That piece still hangs on Rick’s wall today.

“Everybody loved Genevieve,” Rick says. “Everybody.”

Up until the week she died in 1985, Rick says his aunt was still skipping around, vibrant as ever — probably because a tourist just stopped by her shop with a $100 bill.

Millsfield kept up its midnight vote, off and on, until at least the 1960s. In the meantime, other New Hampshire towns also started dabbling in their own midnight voting rituals, some more consistently than others: Hart’s Location, Waterville Valley, Sharon and Ellsworth, to name a few.

And then there was Dixville Notch, which kicked off its own midnight vote in 1960 under the direction of businessman Neil Tillotson.

Like Millsfield, Dixville was a small, unincorporated community that had to take special steps to hold its own elections. Unlike Millsfield, Dixville had its own phone company, which meant reporters wouldn’t need to brawl over a limited supply of phone lines in order to file their stories. Plus, Dixville’s polling place was inside the regal Balsams Resort — a far cry from Genevieve’s family farm.

At the same time, Millsfield’s population and its appetite for the press’s antics seemed to be dwindling. In 1964, news reports said Genevieve and Elmer were the only registered voters left in town. Two years later, the couple lost their 25-year-old son, Elgin, in a plane crash — which was understandably difficult on the whole family, Rick says.

Pretty soon, the spotlight shifted away from Millsfield. While Dixville Notch never explicitly claimed to take credit for starting the midnight vote, its ritual eventually became so entwined with the image of the New Hampshire Primary that Millsfield’s founding role — and Genevieve’s, by extension — were all but erased.

Today, Dixville Notch has its own “First-In-The-Nation” historical marker, commemorating its role as “the first community in the state and country to cast its handful of votes in national elections” since 1960; there’s no marker in Millsfield, just a few miles down the road.

Millsfield revived its midnight voting tradition in 2016, bolstered by the rediscovery of a TIME Magazine article from 1952 that described the community coming together to vote “in the parlor of Mrs. Genevieve Annis’ 125-year-old house.” But that was as far back as many locals knew the story went — including Jackie Hines, who lives in that same house today.

While Hines never got to know Genevieve, she’s heard plenty of stories. And in those, Genevieve sounded strong, creative — the kind of person she’d like to be friends with.

“I wish I could’ve met her,” Hines says.

Like a lot of locals, Hines didn’t know that Millsfield’s midnight vote actually began much earlier than that TIME Magazine story — or that it kicked off in her own home — until an NHPR reporter showed up in her front yard, unannounced, carrying a pile of newspaper clippings and hoping to talk to people who lived at the scene.

The timing was fortuitous, Hines says. Earlier that same day, she reluctantly called a realtor to come look at the house, because she weighing a difficult decision of whether to put it on the market.

“It was just really strange that you came that afternoon and gave me that information about Genevieve,” Hines says. “I felt like she was here, like she was saying, ‘Don't go without, you know — give us the credit here. Give us the credit, and then you're free to go.’ I've done everything I can here.”

Hines still needs to tackle a few big projects before she puts the house up for sale. But she’s recently added one more item to her to-do list: She wants to mark her house, Genevieve’s house, as the birthplace of midnight voting in New Hampshire.

The credit, she says, is long overdue.

For more on the backstory behind the midnight voting ritual, check out NHPR's new podcast Stranglehold, all about the New Hampshire primary.