Every other Friday, the Outside/In team answers listener questions about the natural world. This week, we answered two questions on the same topic.

“I was wondering if you could explain wet bulb temperatures and events,” said M’ris from Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania.

What’s a wet bulb temperature?

There’s a cliche oft-heard in conversations about the weather: “yeah, it’s hot, but it’s not too bad, because it’s a dry heat.”

Turns out there’s something to that. Here’s why.

A wet bulb temperature is the temperature after the effects of evaporative cooling. This measurement matters because evaporative cooling is how we (and other mammals) cool our bodies. It’s the operative mechanism of sweating: our internal body temperature drops as water evaporates off our skin.

But when it’s humid, the air is saturated with water. Essentially, the air is full. Our sweat can’t evaporate, so our body temperature can’t drop. When we hit critical environmental limits, we can no longer cool down by physiological means, and it becomes a matter of survival.

So, what’s that critical wet bulb limit?

“Humid heat stress is really, really dangerous,” said Daniel Vecellio, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Healthy Aging at Pennsylvania State University.

Vecellio studies climate change and human health, and he’s trying to understand the upper limit of what the human body can handle in terms of humid heat stress.

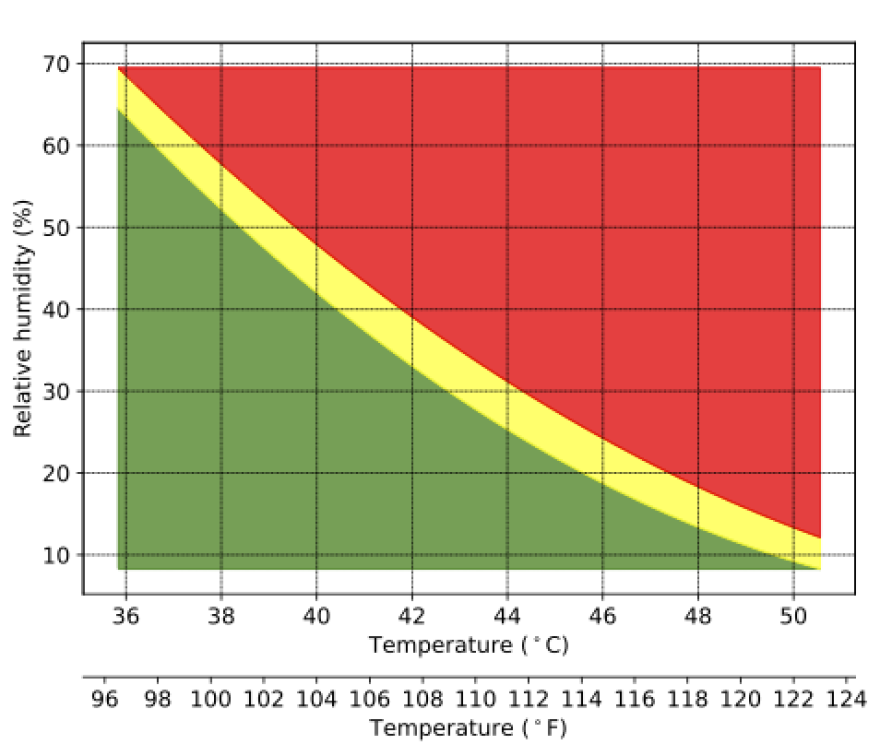

In 2010, researchers came up with a theoretical wet bulb limit of 35 degrees Celsius, or 95 degrees Fahrenheit, at 100% humidity. This is the theoretical humid heat limit for humans.

Vecellio and his coauthors put this theory to the test: they studied people doing physical activity under various conditions in a lab.

In their experiments with young, healthy adults, they found their core temperatures started to rise continuously at wet bulbs of about 31 degrees Celsius, or 88 degrees Fahrenheit, in humid conditions (relative humidities of 50% or above).

That’s a way lower bar than the limit found in that earlier paper.

Vecellio did note that the lived experience will be somewhere in between, and will vary depending on other factors, like age or preexisting health conditions.

How often are wet bulb temperature limits reached?

“[Are there any] places in the world where it already exceeds what is considered easily survivable in terms of the wet bulb temperature, and if so, how do the people who live there adapt to it culturally?” asked Sam in Concord, New Hampshire.

Well, it depends on what we’re talking about.

“That 35 degree wet bulb limit, as of 2010, had not been really seen across the entire world,” said Vecellio.

But the limit identified by Vecellio and his colleagues is more common, and meanwhile, heat waves are getting more intense, longer, and more frequent.

Some parts of the world are already regularly experiencing extreme heat, and will be more likely to see wet bulb limit conditions. These places tend to be close to the equator near warm bodies of water, like the Middle East, Pakistan, and India.

How do people adapt to extreme heat and humidity?

“As Indians, we have been living with high heat conditions throughout, and it was already a difficult thing to do. Now, this additional heat is actually pushing us to the brink,” said Avikal Somvanshi, a data scientist and urbanologist in New Delhi.

Somvanshi explained that we have to stop thinking about heat waves as episodic events and rethink how we live, especially in cities.

“We need to start looking at the cities in a way that they become a shelter from the heat, [rather than] become the heat magnet themself,” he said.

Historically, people used passive design as a tool to regulate temperature, not only in buildings, but also city streets.

“If you look at the old cities of India, the roads were narrow and winding because they didn't want the sun to hit the roads where people were working. But that has kind of disappeared in the modern design,” said Somvanshi.

Adaptive city street design could also mean more shade, green and even white roofs.

The conditions in city streets are important because outdoor workers are among the most vulnerable people in India.

“Working age men are dying… blue collar workers who are forced to work during the peak heat hours during the day,” said Somvanshi.

To tackle heat driven by climate change, we’ll also need to go beyond the physical aspects of urban design, and rethink how we structure our lives. We might consider flexible work times, like shifting outdoor work to the cooler evening hours. We might learn from cultures that take siestas, midday breaks from work or school during the hottest part of the day.

In some workplaces, the pandemic already prompted this shift, but Somvanshi said white collar workers saw most of the benefits.

Air conditioning is another way we adapt our spaces during major heat events, but since they generate a great deal of waste heat and often run on fossil fuel generated energy, they’re an imperfect solution.

Finally, we cannot wait to consider systemic changes because climate-driven heat impacts are not a future problem. They’re already here.

“Heat is already the number one weather-related killer of people in the United States, before the United States are even thinking about reaching these thresholds that we found,” said Vecellio.

Send your question about the natural world to Outside/In by calling our hotline. The number is 1-844-GO-OTTER. You can also send us a voice memo to our email: outsidein@nhpr.org.

Outside/In is a podcast. Subscribe on the platform of your choice.