For the past few months, visitors to the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester have had a chance to spend quality time with the artist Claude Monet. Since July, the museum has had an exhibition, Monet: Pathways to Impressionism, showing works by the famous French painter. This is the final weekend to see it – it closes Monday.

It’s just 4 paintings, in a small gallery with the walls painted deep red. But together, the works tell a story about the artist.

"This is his very first picture that he ever submitted to the salon, and it was accepted to the salon when he was just 24 years old," curator Kurt Sundstrom tells me, as we stand before the first painting in the exhibition, La Pointe de la Hève at Low Tide, 1865. It's a dark, brooding scene - a stormy day on a rocky coast. Someone is struggling to drive a wagon through the surf. Even the horses look cold.

Sundstrom says this early painting is still rooted in the realist tradition that was popular at the time in Paris. But the beginnings of what made Monet so different are starting to show.

He points to a corner of the painting, a pile of stones, where he can see it: "If you look at here along the beach you can see that the brush marks stand out, but they’re representing a stone, they aren’t an actual realistic depiction of a stone, and that’s what we see as impressionism."

To the left, hangs a painting from 4 years later, a bright, dappled scene in a town. This painting, The Bridge at Bougival, 1869, actually belongs to the Currier – it’s their Monet. It was acquired by the Currier in 1949, and it's often out on loan to other museums.

"The houses now are just demarcated just by large patches of color, a roof is just a single brush mark that goes across in red, so things aren’t as they actually are, but as they appear in Monet’s mind."

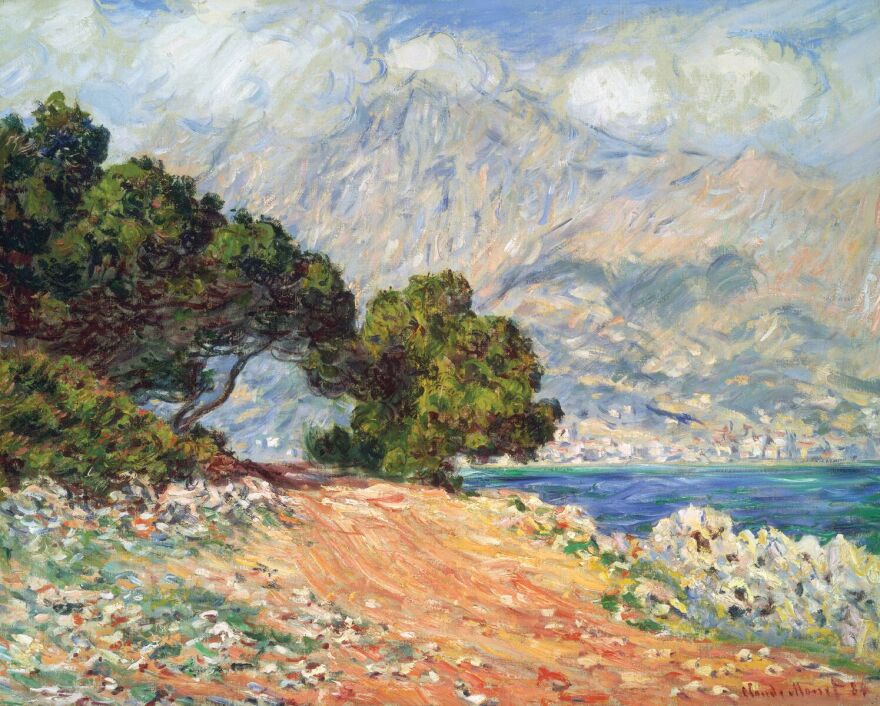

And so we come to the third painting in the exhibition, Cap Martin, near Menton, 1884. "This is the painting where, if you’re going to say, what is impressionism, this is what you’re going to come to," says Sundstrom.

It’s a Mediterranean town, seen from across the bay. Monet’s brush strokes are now thick, the colors vibrant. "You know instead of seeing the tree, you seeing the light coming off the tree and how it’s constantly changing."

Sundstrom says this is what we see in Monet’s later paintings.

In this last work in the exhibition, Charing Cross Bridge (overcast day), 1900, the trains that put out those great puffs of violet smoke aren't even in the painting.

"You don’t even know that the trains are there you can’t even see it, so he’s actually just painting air and light at this point," says Sundstrom.

There’s a single, long bench in the small gallery. Bob Scammon, born in Dover but now living in Texas, sits down and spends a long time looking.

"You know, we spend so much of our lives inside and in cities and all, and seeing something like this to me is, you know refreshing in a way, calming," he says.

Chris Friedrich is visiting the museum from New York City. She's enjoying looking at that Mediterranean scene. "Well it gives me the impression, to use that phrase, of light, color, movement, and a really clear day where you can feel the air and the water," she says.

Sundstrom, the curator, says artwork is meant us to make us feel different, to walk out of the museum and see differently. Maybe even see the world as Monet might have seen it.

So how would Monet see New Hampshire?

Sundstrom guesses he would be drawn to the coast, the rivers...and the winter.

"You know the reflection off of snow versus off of ice is very different, and sometimes that early morning sun coming up, playing off of the trees that have hoar frost on them or something, I think it would be extremely attractive to Monet."

This exhibition, and three of these masterpieces, will soon leave the state. But we’ll still have the Currier’s Monet, and, soon, New Hampshire winter.