New Hampshire’s minimum wage is the lowest in New England. It's the same as the federal rate: $7.25 an hour. Meanwhile, Maine sets its minimum wage at $10; Vermont, at $10.50; and Massachusetts, $11, is on the way up to $15.

For the latest in NHPR's Only in New Hampshire series, listener and lifelong Manchester resident Kathy Staub asked:

New Hampshire is surrounded by states with a minimum wage of $10 or more. How do higher wage commuters impact rents along the border?

Staub works as a field representative for Rights and Democracy NH, a 501c4 that organizes around issues like money in politics and raising the minimum wage. They often canvas door-to-door to discuss the issues with residents.

“I remember being in the low income housing development in Salem and talking to a woman who worked at Wendy's in Massachusetts, and she said, 'I can't afford to work in New Hampshire.' But you drive a few miles away across the Massachusetts border, the minimum wage there is $11 an hour,” Kathy said.

“It really does make a difference… in places like Salem, Nashua, Merrimack, we heard this over and over again: I can't afford to work in New Hampshire.”

At present , New Hampshire has no state minimum wage law, instead tying it to the federal rate- again, $7.25. New Hampshire is one of 14 states at that rate, while 29 states, plus D.C., set their minimum wage above the federal rate.

Over the years, state legislators have proposed bills to raise the minimum wage but so far, none have been successful.

“This can get very confusing,” said Annette Nielsen, economist at the Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau. The office calculates the state unemployment rate and publishes wage survey information and labor market numbers in general.

The Bureau uses a tool called OnTheMap to understand commuting patterns. According to their analysis of the Nashua Interstate region, in 2015 over 80% of New Hampshire workers both lived and worked in the state, although that varies depending on local economies and geographies.

For instance, “[in] the Upper valley, we actually gain workers,” said Nielsen.

Overall, New Hampshire loses commuting workers, although the state gains workers from both Vermont and Maine.

“That dynamic has been true for at least, as far as I know, the last thirty, forty years,” said Nielsen.

But it's probably not a surprise that in terms of labor, New Hampshire’s strongest interstate relationship is with Massachusetts. In 2015, 15% of New Hampshire's working residents commuted to Massachusetts for work. That's almost 94,000 people.

Boston is the main economic driver in the New England region, "whether you like it or not,” said Nielsen.

She explained that labor markets “do not care about the state border,” and commuters are more likely to earn higher incomes. They’re also more likely to be men - and when women do commute, they are less likely to commute as far. And people earning lower wages generally do not commute long distances for work.

Nielsen says those higher wage commuters are raising rents along the border. But what does that have to do with differences in minimum wages in bordering states?

Not much, according to Bill Ray at the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority. Supply and demand is the driving force behind high housing prices. Right now there’s a lack of supply, not just in New Hampshire, but across the country.

“If there are people that want to live here and there are not enough houses for them to do that, then prices will go up,” said Ray.

“We’re seeing that now… that’s exactly what’s happening. The people with higher incomes can compete better for the housing, and landlords and owners will charge what market will bear. So if you’re very low income, you don't have that much impact on pricing.”

Brian Gottlob, principal of PolEcon research in Dover, says this creates a very difficult situation for low wage workers.

“The housing market is just like nature. It’s just indifferent to difficulties of lower on the food chain,” said Gottlob.

“The housing market doesn't care about those who have less ability to purchase, or less ability to pay. The housing market responds to effective demand. If there people willing to pay who have ability to pay, then prices will rise to meet that level.”

Boston has expanded to the point where southern New Hampshire can be considered an extension of the metropolitan area, which influences the rental market, wages, and overall cost of living.

“New Hampshire is now a high cost of living state,” said Gottlob. He added that while cheaper pockets still exist, high cost of living is largely a result of housing prices.

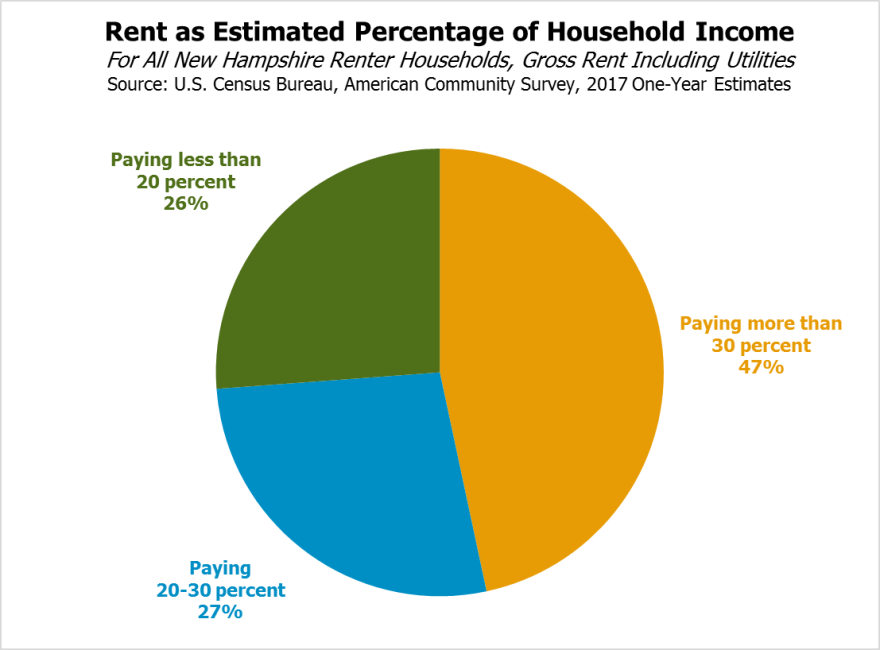

The New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute calculated that 47% of households in the state are paying more than 30% of their household income towards rent and utilities -- which means almost half of New Hampshire households are defined as cost-burdened.

If employers ever argued they could pay workers less money because New Hampshire had a lower cost of living than Massachusetts, Gottlob says “that’s simply not the case anymore.”

“We are lower but, boy, that gap has narrowed over last decade.”

How many people make $7.25 an hour in New Hampshire?

“Very few,” said Gottlob. “It’s surprisingly few.”

According to 2017 data published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, about 8,000 hourly workers earn at or below the minimum wage.

“It’s under two percent. That sounds insensitive, and I don't want to minimize the difficulties that low wage workers have, but it’s a small percentage of our workforce,” said Gottlob.

“[$7.25 an hour is] certainly not a wage that you could, as an individual, find a rental property, let alone purchase housing.”

With a tight labor market and 2.6% unemployment rate, competition for workers might pressure employers to pay higher wages in New Hampshire.

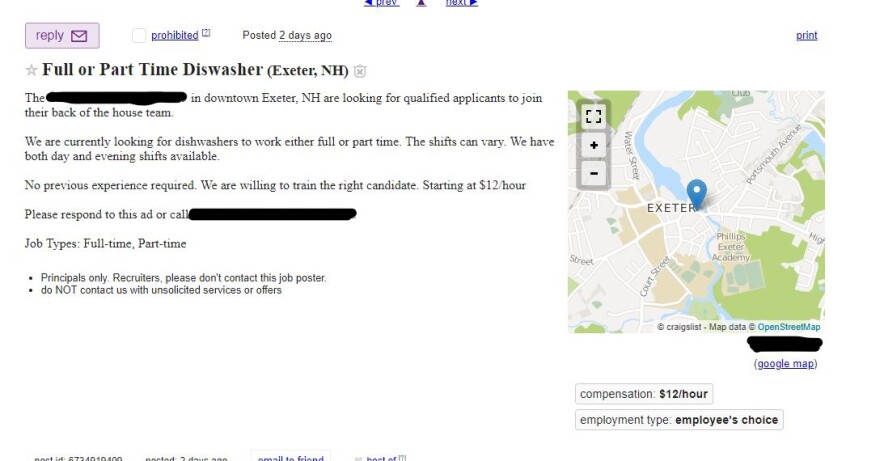

A 2017 survey by New Hampshire Employment Security found that the mean wage for food preparation and serving-related occupations was $12.39 an hour, the lowest of all occuptions surveyed.

But while workers might be making above New Hampshire's minimum wage, even an hourly $8 or $9 rate is still below minimum wage in Vermont, Maine, or Massachusetts, or anywhere else in New England.

Gottlob thinks that the minimum wage debate can miss the point. In 2013, New Hampshire considered raising the minimum wage to $8.25 and then to $9 an hour. Gottlob calculated that, at the time, just under 10,000 people were earning the minimum wage.

But at an hourly wage of $8.25 or below, he found 26,000 workers, and about forty thousand people earned $9 or below. He'd discovered that other, more meaningful earning thresholds.

“In a lot of ways... this minimum wage number is really kind of artificial," said Gottlob. "Take a look at: where’s the labor market setting these markers?”

“The federal minimum wage at $7.25 to me is not that significant of a marker. It’s a number. But labor market itself has made that number irrelevant,” said Gottlob.

But Gottlob suggested that wage markers a dollar or two above the minimum wage - perhaps at the level of the minimum wage in Vermont of Massachusetts - might tell you a lot more about the size of the population likely to be struggling with housing.

As a consequence of rising housing costs, worker are spreading themselves out and living further from their jobs, including higher earners. But of course, those earning higher incomes have more choices and control over where they land.

“That’s really the most fundamental impact. It changes nature of communities,” said Gottlob. "Lower wage workers generally get priced out of some communities. They move further out and further away from employment opportunities.”

“It has changed the dynamics of southern New Hampshire.”

In describing this dynamic, Gottlob essentially defines gentrification, in which wealth stratifies communities, creating towns, streets, and neighborhoods defined by socioeconomic classes.

If wages are rising, even on the low end of income distribution, does this mean that the market is working?

“The question that people are asking, and what is driving a lot of minimum wage debates, is, 'is the market working fast enough or well enough to address the difficulties that lower wage workers are having relative to housing prices?'" said Gottlob.

"And bottom line is for most people, at least in New Hampshire, you have to say 'no.'"

"The market is working in that wages have risen, but they're not rising at a rate that will make it significantly easier for lower wage workers to find housing at a reasonable portion of their income levels,” said Gottlob.

As a society, we simply haven’t built enough housing the past decade. Though both Gottlob and Ray said it's hard to explain precisely why housing supply is so low, it's likely due to a combination of factors including demographic shifts, a labor shortage, and lingering reverberations of the recession.

In the meantime, the Boston metropolis and rental market continues to seep into surrounding states, the population has grown, and young people age into starting their own households. So, there’s a need for solutions, perhaps development of multi-family housing units.

But if the housing market simply does not respond to lower incomes, public policy and incentives could be a place to look for changes.

Do you have a question about some quirk of New Hampshire or your community? Submit it here at our Only in NH page, and we could be in touch for a future story.