The past four years, from the Mueller investigation, the first impeachment of President Trump, and the discussions about presidential pardons, have demonstrated the complicated Constitutional questions of how a sitting President may be held accountable. After the House voted for a second time to impeach President Trump, we talk about what's next, as we near the transition of power. What do you think Congress should do next?

Air date: Thursday, January 14, 2021.

Produced by: Christina Phillips

GUESTS:

- Brian Kalt - Professor of Constitutional law and the history of the presidency at Michigan State University. He is the author of Unable: The Law, Politics, And Limits Of Section 4 Of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment and Constitutional Cliffhangers: A Legal Guide for Presidents and Their Enemies.

- Congressman Chris Pappas - U.S. Representative for New Hampshire's 1st District.

The following is a full transcript of the show. It has been lightly edited but may still contain errors.

Laura Knoy: From New Hampshire Public Radio, I'm Laura Knoy, and this is The Exchange.

Laura Knoy: President Trump is now the first American president in history to be impeached twice. The U.S. House voted yesterday in favor of an impeachment resolution that cites the president's incitement of insurrection in its words. The vote was 232 to 197, with 10 Republicans joining House Democrats today. In Exchange, a legal take on what this means and Exchange listeners join us. What's your reaction to this impeachment vote? What questions do you have about what it means or what happens next? Later in our show, we'll be joined by New Hampshire Congressman Chris Pappas.

Laura Knoy: But helping us out for the hour is Brian Kalt. He's a professor at Michigan State University and a scholar of constitutional law and the history of the presidency. He's written two books on what the Constitution says about punishing presidents. The latest is called Unable, which covers the 25th Amendment. The other is Constitutional Cliffhangers: A Legal Guide for Presidents and Their Enemies. And Professor Kalt, a big welcome. Thank you very much for being with us.

Brian Kalt: Well, it's my pleasure.

Laura Knoy: Well, as someone who's written two books and on this topic and studies it all the time, presidential accountability, what stood out to you yesterday about those proceedings?

Brian Kalt: The impeachment was interesting in a lot of ways. One is the timing of it so close to the end of the term, that raises a lot of interesting issues. The other is, and people mentioned this a lot in the news, the 10 Republicans that joined with the Democrats on the impeachment. And they kept saying this is the most bipartisan impeachment in history. And it is. What that shows, though, is just how low the bar is for bipartisanship and impeachment that only 10 was enough to break that record. And then the interaction of impeachment with the 25th Amendment leading up to this was very interesting, too. And I think it exposed a lot of misunderstanding about how the 25th Amendment is supposed to work.

Laura Knoy: Well, that's really interesting. And when this first happened last week, we got so many questions from listeners about the 25th Amendment. So what was exposed about the 25th Amendment, Professor Kalt, in this whole proceeding we've seen over the past week?

Brian Kalt: Well, people have this idea of the 25th Amendment, Section four as being kind of like a constitutional shiv, like you, just the vice president and cabinet take it out and the president is cast off into the abyss. And it doesn't really work that way. It really is designed for those situations where the president is incapacitated, like in a coma or something. And then if the president is OK, if he's able to say that he's OK, it's set up in a lot of ways to protect him. And you can still use the 25th Amendment in those situations. In an extreme case, the president's running amok, but it really is set up to not work if the president says that he's OK, to not work unless a very high bar is cleared. So talking about it is just an alternative to impeachment as a way to get him out faster. What this showed is it doesn't work because it's structured not to work in a situation much like this.

Laura Knoy: That's interesting. So we all kind of got an education on the level of incapacitation that needs to be present for that 25th Amendment to kick in. Did anything about this whole process - again, everything's unfolded very quickly - did anything surprise you, Professor Kalt?

Brian Kalt: I was surprised, I guess I would have thought I was cynical enough by now, but I was surprised at how quickly the House Republicans, most of the House Republicans, were ready to back into the partisan role and to defend the president to talk in the debate yesterday, not about what the impeachment article was about, but about how they think he had done a great job, which is not relevant. But it just brought out this partisan nature of things. And usually, I'm just thinking back to the Clinton impeachment, the question was, OK, everyone agrees that what happened here was unacceptable. The question is, what do we do about it? And I was so surprised at the extent to which the Republicans weren't even starting with that: what happened here was unacceptable. Some of them did, but a lot of them didn't. And I suppose that reflects the polling that I've seen and the extent to which Republican voters are OK with what happened. 20 percent said the storming of the Capitol was great in the poll that I just saw.

Laura Knoy: Well, besides the 10 Republicans who voted in favor, as you just alluded to, Professor Kalt, there were some who did say, look, what the president did was wrong. But as House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy said, there were better ways to punish this president than impeachment. Let's hear from House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy.

Kevin McCarthy: [Recording] "I believe impeaching the president in such a short time frame would be a mistake. No investigations have been completed. No hearings have been held. What's more, the Senate has confirmed that no trial will begin until after President-elect Biden is sworn in. But here is what a vote to impeach would do. A vote to impeach would further divide this nation. Vote to impeach will further fan the flames of partisan division. Most Americans want neither inaction nor retribution. They want durable, bipartisan justice. That path is still available, but is not the path we are on today. That doesn't mean the president is free from fault. The president bears responsibility for Wednesday's attack on Congress by mob rioters. He should have immediately denounced the mob when he saw what was unfolding. These facts require immediate action by President Trump, accept to share responsibility, quell the brewing unrest, and ensure President-elect Biden is able to successfully begin his term. And the president's immediate action also deserves congressional action, which is why I think a fact finding commission and a censure resolution would be prudent. Unfortunately, that is not where we are today."

Laura Knoy: Again, that's House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy speaking on the House floor yesterday as the House voted to impeach President Trump. Couple of legal points for you there from that clip. Professor Kalt, he said, Kevin McCarthy said what a lot of Republicans said yesterday. Yes, there was a lot of blame for the president, but this process is rushed. No investigations, no hearings. Does that have to be, Professor Kalt, part of the impeachment process?

Brian Kalt: No, it doesn't have to be. It certainly helps - the better you develop the case, the better it'll stick. But if you're in a situation where you have enough information without that to make up your mind, then go ahead. We've all seen what the president has said on TV, what he said in his tweet. It wasn't a coincidence that these people showed up at the Capitol waving Trump flags and repeating some of the things he'd said about the election. And the connection is clear enough that I think there's enough for representatives to draw their conclusions about what the president was doing regarding the election and to make that judgment.

Laura Knoy: McCarthy also mentions censure in that clip, what is censure, Professor Kalt?. What does it do and what doesn't it do?

Brian Kalt: Censure is just a resolution, so the House, the Senate, they can pass resolutions expressing the sense of the House or the Senate on whatever they want, they could have a resolution saying that they appreciate peanut butter and jelly sandwiches if they want.

Brian Kalt: It doesn't have any meaning other than just sort of saying that that's what they think. But censure would be a blot on anyone's record. President Jackson was censured and that really stuck in his craw. And he eventually got the Senate to reverse their their censure because it really bugged him. But it doesn't have any binding legal effect at all.

Laura Knoy: Well, and to that argument that we heard from Kevin McCarthy and we heard from a lot of Republicans yesterday, they said, look, yes, he should be held accountable, but he's almost gone anyway. He'll be out of office in a week. What is the point of this? That's what they said yesterday. You, though, Professor Kalt wrote in The Washington Post recently that, quote, Impeaching someone who has left office is usually pointless, but in some cases, it might serve national interests. When is a late impeachment pointless, Professor Kalt, and when is it important?

Brian Kalt: Generally, it's pointless if the main point of the impeachment was to remove the person from office, so the only successful impeachment in our history have been of judges. And so usually what you're worried about with the judges, that they're still a judge. So once once they resigned, if you've impeach, once they've resigned, there's not really much point in going forward with the case. But there is another function that impeachment provides, which is to provide deterrence and accountability. And so it might be important, for instance, in a case like this to say, hey, if you commit impeachable offenses, we're not going to give you a pass just because you did it toward the end of your term. And then there's also another consequence of the impeachment conviction. The Senate can choose to disqualify the convict from holding future office. And so if it looks like that might happen, then the Senate might want to do that. Of course, they still need two thirds to convict. And it's also not entirely clear that the offices that this disqualifies you from, if they do that, includes the presidency. So even if they did that, the president could argue that he can still run for president. But if there were enough Republicans willing to step up and say this is unacceptable, we can't have this kind of behavior in the presidency, then they might want to also disqualify him.

Laura Knoy: So let's just remind folks, Professor Kalt, the House impeaches, but that doesn't mean the person is gone from office, punished and so forth. So the Senate has to convict. Is that the right language there, Professor Kalt?

Brian Kalt: Exactly, the House impeaches by simple majority, and that doesn't have any legal effect. It is an accusation tha,t it's like an indictment in a way, but the Senate can acquit, as they did last time and as they did with Presidents Johnson and Clinton. And an impeachment without a conviction has no consequence other than, like censure, just sort of being a blot on someone's record.

Brian Kalt: There's some confusion. Some people think that it affects the pardon power. That's not true. The president has all of his powers up until the point that he's convicted or his term runs out or he resigns. But just the impeachment by itself just sends the case to the Senate. It doesn't.

Laura Knoy: It's just a charge saying we think this person did bad things here, Senate, you decide. It's almost like the House is the prosecutor and the the Senate is the judge and the jury. Is that a reasonable analogy?

Brian Kalt: Yeah, or the grand jury. It's just saying there's enough here to go forward with the case. And the bar is relatively low. A simple majority in the House isn't that hard to to muster. And if impeachment all by itself had any consequences, I think you would have seen a lot more impeachments when President Obama was in office and had a Republican House. If they thought they could have stripped his powers just by impeaching him without a conviction, I think they would have done that. But it doesn't.

Laura Knoy: I've been reading legal scholars, Professor Kalt, going back and forth on what the Constitution says about late impeachability, again a week before someone is out of office. What's the disagreement about, Professor Kalt? You know, I hear, I've read that you've said the Constitution provides powerful evidence for late impeachability, but then I read other scholars saying, no, you can't do it this late in the process, so help us out there.

Brian Kalt: I like when I hear people use the phrase late impeachment or late impeachability, I actually coined that phrase. I wrote a fifty-thousand word article back in 2001 where I dug into this and I said -

Laura Knoy: Wow, who knew, right?

Brian Kalt: Well, I thought it was important when it wasn't really an issue to just really dig into all the evidence and see what it said about this question, because on its face, it seems like an absurd thing. If you look at the Constitution says impeachment, you get removed if you're convicted, and it's president, it doesn't say ex-presidents, but when you dig into the evidence, there's a lot more there. And so my response is - I can't tell people, "well, go read the article," it's more than one hundred pages long - but I can say that most of the arguments I've seen saying, "oh, this can't be done," don't really dig in to that evidence, don't really have an answer to a lot of the things I found there. So basically, the argument that you can do it is impeachment is not just about removal. The Constitution says removability is mandatory if you are, I'm sorry, removal is mandatory if you're convicted. But that just means if you are in office and you get convicted, then you get removed. It's not a thing. Those are the [audio error] can be impeached. And looking at the history, late impeachment was a thing at the time they wrote the Constitution that it was, there was a late impeachment case going on in England at the time. They talked about it in the Constitutional Convention, but they didn't have a problem with it being a late impeachment. And they made all sorts of exceptions so that it wouldn't be as broad as British impeachment, but they didn't mention this one. And then again, that issue of deterrence that needs to go all the way to the end of the term. And finally disqualification - disqualification was important. They made that a possible result of conviction, because they thought it was important to disqualify people. If you can't be disqualified, if you can't be convicted, once you're out of office, then anybody would be able to avoid disqualification just by resigning right before the Senate voted. So it would be a dead letter if late impeachment weren't available.

Brian Kalt: But the most -

Laura Knoy: That's interesting. Yeah, go ahead.

Brian Kalt: But the most important point is whether you believe it can be done or not. It has been done. The very first impeachment case, the trial was of someone who was already gone. And the Senate dismissed it for other reasons, but they said they were okay with that. And the Secretary of War in 1876 resigned, got impeached after that anyway, and the Senate had a trial and the argument was made - as it will be made in Trump's case - that you can't try someone if they're already gone. And the Senate took a specific vote on that question and decided that they did have jurisdiction. So there are precedents.

Laura Knoy: So let me make sure I have this right, Professor Kalt. So are you saying that if President Trump resigned on his last day, he could avoid conviction by the Senate?

Brian Kalt: No, well, those those who say that late impeachability is not possible would say that if he resigned or if his term ran out, which I think is more likely, that the case would have to be dropped. I just, I disagree.

Laura Knoy: I see. You say that no matter what, given the precedence and given what you read in the Constitution, that you can continue to vote to convict even after somebody has left office - late impeachability.

Brian Kalt: Yeah, and the case of the Secretary of War, it stands for the proposition that they don't need to even impeach him before he left office. They can wait till he's gone to start the process.

Laura Knoy: Got a couple of questions from listeners coming in, Professor Kalt. Well, Richard says, I listen to the House of Representatives, quote, "debate" over the resolution to encourage Vice President Pence to invoke the 25th Amendment. It seemed that there was no debate at all, just a stating of opinions and allegations. I realize each speaker had very limited time. Nonetheless, where was any attempt to put forth reasoning and refute arguments made by the other speakers?

Laura Knoy: Do you want to say anything, Professor Kalt, about the whole 25th Amendment discussion that Richard talks about?

Brian Kalt: I thought I thought the whole 25th Amendment discussion was a little odd because it was clear before they even started the debate that Pence had said unless the situation changed, he wasn't going to do it. So I think it was more symbolic. There might be a role for Congress, in a case where maybe the vice president and cabinet are skittish, they're not sure if they would have the votes, because the disputed case - if the president says he's OK and the case goes to Congress - you need two thirds in the House, two thirds in the Senate, or the president gets his power back. So the vice president and cabinet wouldn't normally want to do that if they didn't think they had the votes there. So maybe if they wanted to communicate that the votes were there, if this was in the middle of the term, that would make sense. But that's not what they were doing. So it just, I don't know. It seemed pointless to me and a drag the 25th Amendment into something where it didn't really fit.

Laura Knoy: Oh, that's interesting. So why did they even bother doing it in Congress when this is in fact an executive function, has to happen at the White House? Is that what you're saying, Professor Kalt?

Brian Kalt: Yeah, I think the reason they did, I understand why they did it, it was because they see Section four of the 25th Amendment as the only way to immediately take power away from the president. Impeachment takes time and the president's in charge in the meantime. Section four takes his power away immediately. And they were worried what might he do with his presidential power in the next few days? Who might he pardon? He's the Commander in Chief, what could he do? And so they weren't thinking, what is this structure? How is this supposed to work? They were just saying, here's something that might work. We can't just sit here and do nothing. Let's try this thing. It's just not the tool for the job in this case.

Laura Knoy: Yeah, so big, a big civics lesson for all of us. Thank you for writing in, Richard. And here's another question from Mark in Epping, who says, Given the time that Trump remains in office, shouldn't Congress use the 14th Amendment to prevent President Trump from running for office again? Marc, I'm really glad you wrote, because this is a question I had, too. The 14th Amendment. Professor Kalt?

Brian Kalt: Yes. Section three of the 14th Amendment passed after the Civil War, said anyone who's a public office holder who engaged in insurrection and rebellion - meaning at that time the Confederates - would not be able to serve in public office going forward. The problem with using it here is, one, it's not clear that the president is covered by that, same thing as disqualification in an impeachment. It talks about officers under the United States. It's not clear that the presidency qualifies under the Constitutional language of that. The second is it doesn't make clear how we decide who declares that the person is an insurrectionist and what's the process for that? Who's the decision maker? There's no there's no details there. And so it would be very awkward if they took a majority vote of the House and Senate that would be challenged in court. If someone I suppose, looking at how it was used in the 1870s before it was sort of rendered a dead letter, someone could say, hey, he's not actually President right now. He's an insurrectionist. So anything he does as President is null and void. And then a court could decide that if the president does something and someone wants to challenge the validity of that action, the court would have to decide does 14th Section three apply here? But again, it's not as clean and clear as impeachment or 25th Amendment where it's spelled out what the process is. So I don't know, I suppose by the same token, that they'll take whatever tool might do the job. They might try it. But it's it's very murky as to how that would work.

Laura Knoy: Wow. All right. Well, thank you for writing in to those listeners. And Professor, David's calling in from Keene. Hi, David. You're on the Exchange. Welcome.

Caller: Hi. OK, my question is pretty simple, could he be charged criminally, could he be charged? I know reckless is a term that gets used in courts a lot. I mean, he seems pretty reckless in what he did. Could he be charged criminally after he leaves office regarding this, maybe inciting a riot or who knows? Prosecutors will decide that.

Laura Knoy: David, I'm glad you called because I wanted to ask you this, Professor Kalt, anyway. Some people have been saying, look, don't bother with impeachment. Once he leaves office, he's going to face all sorts of lawsuits. So what about that? And David, thank you again.

Brian Kalt: There is no question that presidents can be prosecuted once they've left office. I'm not an expert on the criminal law of any of the stuff he's charged with - inciting insurrection, or the call to the Georgia Secretary of State, or any of his issues in New York that he's going through.

Brian Kalt: But while it is disputed whether you can prosecute him while he's in office, there's no question that once the president is gone, he can be prosecuted. And impeachment, late impeachment, one reason to do it might be he's not facing any other consequences. So that is sort of tricky. They say, well, let's not do it because we'll let the criminal law do its job. On the other hand, if he is charged and convicted of something, then late impeachment makes a lot of sense because they don't have to go through the whole process. They've got a court already deciding what he did and they can just sort of very quickly say, OK, let's disqualify for that. So there is there is an either, or, or both quality to the criminal process here.

Laura Knoy: Here's a question that we've gotten from several listeners, Professor Kalt. What are the possibilities that this president could pardon himself or anybody else associated with that attack on the Capitol?

Brian Kalt: Yeah, that's a big question. He was already talking about pardoning himself before this happened, his pardon power is very broad and there's an argument that's been made that if you've been impeached for something, you can't pardon people for the crimes associated with that. Not a very convincing argument to me. I don't think it squares with the case law or the history or the authorities on this.

Brian Kalt: So basically, he could pardon for federal charges, anyone he wants except himself. That's under a lot more of a cloud. So maybe he can. Maybe he can't. I've been arguing my first, very first article that I ever wrote in the Law Journal was in the mid 90s about whether the president can pardon himself. And I set out the argument that he can't. But there are arguments on both sides and there is no precedent.

Brian Kalt: So he can certainly try. I think there's good reason to think that it might not work. And certainly if he does do that, they could add that as another article of impeachment. If he pardons himself, if he pardons the insurrectionists, that could be abuse of the pardon power. That could be another article added to the House's case.

Laura Knoy: Wow. So you're saying it's unclear whether the president could pardon himself or other people involved in inciting the riot?

Brian Kalt: Well, I think it's more clear that he can pardon those other people, but pardoning himself is sketchy at best.

Laura Knoy: I like that - sketchy at best. So, well, we'll have to see what plays out, but I know that's a question that a lot of people have, so we'll set that aside for the moment and just go back to listeners who have lots of questions about how this happened legally yesterday and what happens from here on out. Again, just a reminder, the president was impeached but has not been convicted by the Senate. And we don't know exactly how and when that process is going to roll out.

Laura Knoy: But for now, Ginny in Center Harbor writes, given the number of cabinet members who resigned, would the Vice President have had enough members to agree on enacting the 25th Amendment should he have chosen to do so? Ginny, it's a good question and Professor Kalt?

Brian Kalt: I get that question a lot.

Laura Knoy: Really?

Brian Kalt: Oh, yeah. So for years, because the president has had a lot of turnover and there's even a perception people have had that the whole Cabinet was acting secretaries or most of them were. We're at five out of the 15 now. So for the 25th Amendment, it's not the Cabinet-level people like the Chief of Staff or the Trade Representative, it's just the 15 official Cabinet departments. So you need a majority. There's no quorum requirement. So you need eight out of the 15. It's not clear whether acting secretaries count or not. There's conflicting authority on this. And I think that they could, but that would be challenged. So what they would need to do is make sure that they have a majority with the acting and a majority without. So eight out of the 15, if you count them, would have to sign on. And then six out of the 10 would have, of the 10 that are confirmed not acting, would have to sign on. So it's doable. You would just need to make sure you had a majority both ways. Really the only- Oh, go ahead.

Laura Knoy: Well, I was just going to say, but Mike Pence, right, the vice president, he's the first step in that process. Is that right, Professor Kalt?

Brian Kalt: Well, he has to sign on, so you need the Cabinet majority and the vice president, but there's no requirement that he be the one that starts it. The Cabinet, could start it and present it to him. He could start it and present it to them, it could go either way.

Laura Knoy: Ok, well, I'm glad for the question, but in terms of this 25th Amendment thing, you know, basically at this point, Professor Kalt, right, that ship has sailed. That's not a possibility.

Brian Kalt: I think it's still on the table, it's still there, even if they're not using it now. So if President Trump started doing some things, if things started spiraling out of control and it was the only way to stop an imminent catastrophe from happening, which on Wednesday last week, they were talking, the cabinet reportedly was talking about invoking it because things were spiraling out of control, but then things quieted down and so they didn't. But things could spiral out of control in five minutes. So it is still there as a possibility.

Laura Knoy: Oh, that's interesting. OK, so that ship has definitely not completely sailed.

Laura Knoy: Lots of questions out there about the legal implications of this, about what happens next. Coming up, we will answer more of your questions about impeachment, other mechanisms like the 25th Amendment to hold elected officials accountable. And we're going to talk for a few minutes with New Hampshire Democratic Congressman Chris Pappas.

Laura Knoy: This is the Exchange, I'm Laura Knoy. This hour, we're answering your questions about impeachment and presidential accountability, given that yesterday the U.S. House voted to impeach the president for an unprecedented second time. Now, joining us for this segment of our show is New Hampshire U.S. Congressman Chris Pappas, a Democrat from Manchester. Congressman Pappas. Welcome back. Good to have you on the Exchange.

Chris Pappas: Hi, Laura. Good morning.

Laura Knoy: So you voted in favor of impeachment yesterday? No surprise House Democrats did with an overall margin of 232 to 197, 10 Republicans joining Democrats. What's your reaction, Congressman Pappas, to that vote total? Did you expect more Republicans to jump ship?

Chris Pappas: Well, it was a solemn day at the Capitol, and it was the day that really we couldn't have foresaw even a little more than a week ago. But here we are and one of my colleagues remarked in the speeches that this was significant in that we were deliberating at the scene of the crime, essentially. And I think that it wasn't lost on us, the gravity of what transpired on January 6th. The fact that in the words of Liz Cheney, who's the third ranking Republican in the House, that Donald Trump had assembled this mob and had lit the match. The fact that she and nine other Republicans supported this article of impeachment I think is a good sign. I had hoped that there were more that would have put the country first. We all saw what we saw and there were very few people defending the words and actions of Donald Trump yesterday. Some said that perhaps this wasn't the right vehicle to address it as he's leaving office. But really, this is the only vehicle we have available to us to address the abuses of the executive and high crimes and misdemeanors. And if we didn't utilize this process in this instance, I'm not sure where you use it in the future or if this fundamentally changes how a president conducts himself and the types the type of language that he feels he can use in the future.

Chris Pappas: So I think we needed to act. I'm glad that we got Republicans on board. We'll see what the Senate does with it next. But I do hope that we can get on with the tough business of healing the country and bringing people together. And that's going to require our Republican friends and colleagues to be brutally honest about the role they played in stoking these conspiracy theories, in denying the will of the voters from November, many of whom voted to uncertify election results just about a week ago. So here we are. And I think it's going to be a long road ahead. But we all have got to commit ourselves to this process to unify our country. I think yesterday's vote was the first step in that.

Laura Knoy: Well, to that point, many Republicans who spoke yesterday said impeachment will only stoke divisions at a time when healing is needed. Republican Representative Andy Biggs from Arizona, who was one of the leaders of "stop the steal," he said, you know, instead of stopping the Trump train, his movement will grow stronger. You have made him a martyr. What about that, Congressman Pappas? Could there be a backlash among Republicans broadly or Trump supporters specifically to this impeachment vote?

Chris Pappas: Well, this is a time for leadership and I think it's a time for leaders in the Republican Party, and we've seen a few of them do this, speak the truth to the base, because for too long they have cowed to them. They have incited the kind of behavior that we saw last week. They've used incendiary language. And, you know, just the whole premise of this "stop the steal." Well, you know who stopped the steal? It was the bipartisan vote we got on the night of January sixth to certify the election results and confirm the will of the people and stop the effort to try to undermine those results. So it just is really amazing to me the number of calls we heard for unity from those that supported overturning a popular election on January 6th. And so I think the process of unity has to include them, but they have to do some soul searching and be honest about what's been going on and stop just playing to the base and understand that they have a role that's far greater than that. Our democracy is resilient, but, you know, it is also fragile at the same time. And I think we saw the fragility on display when our Capitol was overrun. And we all have a responsibility to try to bring some stability and to work with the new administration when the new president's sworn in on the 20th.

Laura Knoy: Here's an email that we got from Scott, Congressman, that relates to something I want to ask you about. Scott says, What is going on in our national government is like a real life version of Hydra and the Justice League. By the way, that's a reference to the Marvel Comics universe. Hydra's a secret organization created by an alien race, has Nazi ties in World War Two. Just in case listeners are wondering what that is. Scott says we need investigations to root out the people in government who have, hold no value to democracy. Scott says they are fighting for a completely different form of government.

Laura Knoy: Scott, thank you for writing. And I did want to ask you, Congressman Pappas, about an investigation now underway that several Republican congressmen might have brought rioters on a reconnaissance mission the day before the attack. What more can you tell us about this, Congressman? Have there been any new developments? What's sort of the buzz on Capitol Hill about this investigation into whether some members may have actually helped this happen?

Chris Pappas: Well, you know, we're all talking about it, and actually, as I think back, you know, the period from our swearing in on January 3rd, leading up to the sixth, we knew that that was going to be a flashpoint day on Capitol Hill. We were told to use the tunnels, to not go outside, and expect additional security protocols. I also noticed, you know, groups being led through the Capitol. And this is a time where the Capitol complex is not open to the general public and not open to the kinds of tours that we used to see pre-COVID. So that is definitely going to have to be looked at. Additional protocols have been put in place, including metal detectors leading into the House floor. We have some colleagues who are intent on carrying arms with them on the Capitol complex, which runs counter to the security protocols. And also what's, you know, even in the District of Columbia, you know, sort of the laws that they're floating. And so I think that we've got to have a top to bottom review here. I think we need to focus on security. There is going to be a 9/11 style review, a bipartisan review by the relevant oversight committees. But in terms of the investigation of, was any inside knowledge available to these rioters? I think if there's credible information, it has to be investigated.

Laura Knoy: So tours nowadays, as you said, Congressman, are noticeable given COVID. You know, tours can't just wander the halls of Congress the way they used to. Are you telling us that you also saw what was a noticeable number of people getting tours?

Chris Pappas: Well, I saw groups and you would pass sometimes groups going through the tunnel between the office buildings in the Capitol. And I remember seeing at least a couple in those days between January 3rd and January 6th. So I don't know what that all means. It could just be that there were new members of Congress who had guests from out of town who were, you know, family members who were there to see them being sworn in or at least see it remotely, or maybe it was something more than that. So I think if there's evidence of anything, it should be looked at by the relevant agencies. And I think that's exactly what will happen here.

Laura Knoy: What action should Congress take to hold these members accountable, Congressman Pappas, if indeed it does turn out that a couple of them were involved?

Chris Pappas: Well, expulsion, clearly, anyone who was involved in the incitement of the riot that we saw should be expelled from Congress. There were at least a couple of our colleagues who were there at the, quote, "stop the steal" rally on the Ellipse and used language that mirrored what the president was saying and even went beyond that. And they were a couple of the chief organizers of the event. So I think we have to look at that. Look, we do want to turn the page and focus on the important work ahead, but there also has to be accountability. This is the United States of America. We are not a country that condones violence and political violence. And in. At the citadel of our democracy, the US Capitol - which belongs to everyone, by the way - we've got to make sure that it is a safe place where processes can go forward and where no one is looking to actively undermine that process and the will of the people.

Laura Knoy: Speaking of language, there's been a lot of scrutiny on social media organizations, Congressman Pappas, that allowed this type of planning and advocacy for violence to take place on their platforms. I know Congress has been looking at social media organizations from many different angles for the past couple months. Now, given what's happened, what should Congress examine when it comes to the role that these platforms play in helping violent groups organize?

Chris Pappas: I think you're going to continue to see a ramped up review of, you know, the laws that pertain to these social media giants, and I think it's appropriate that some of them have taken the step of taking down accounts that have used hashtags like "stop the steal" and have used violent language. There's no room for that. And I think you can balance free speech while also making sure that people are safe. And that information like details about how to join a group that's storming the Capitol are being perpetuated online. So I think there's going to be a long, hard look at that by Congress. What is really alarming to me is that we knew the date of January 6th was significant. We knew there were groups being organized to come to Washington and target us that day. But we didn't know the full extent of the intelligence that was available. And I think there was a breakdown at the leadership level of the Capitol Police, the sergeant-at-arms. And I think there needs to be a full top to bottom review of what information was available and what additional steps were taken to respond to it. I think we left ourselves really open to the attack that happened that day. And I want to know why.

Laura Knoy: I know we only have a couple more minutes with you, Congressman. I did want to ask you, though, on the other side, some conservative groups are saying, hey, their free speech is being silenced by so-called big tech. Do they have a point, Congressman?

Chris Pappas: Well, I think it's ridiculous, the number of people I've heard complaining about losing followers on Twitter, on Facebook. The fact is these are accounts that are perpetuating these kind of violent, you know, memes and posts. And there really should be no space for that, especially when it results in what we saw happen at the Capitol last week. So I think that absolutely we need to respect free speech, political speech, the right to protest - what we saw at the Capitol was not a protest. And we need to make sure that in the immediate future, the inauguration of Joe Biden is safe.

Chris Pappas: There are additional layers of security to that event, given that it's being run by the Secret Service and the National Guard is going to have a significant presence there. So I'm concerned about how we get through this tough period right now and identify additional threats. I think we'll have that longer conversation about how to balance the rights of individuals with the need to keep our society safe.

Chris Pappas: And, you know, I think those who are complaining about being shut out of certain platforms or, you know, losing followers, well, you know, when they participate in that kind of behavior, I think that's appropriate that that's happened.

Laura Knoy: You know, here's an email from Dave in Bow that just came in who says I'm an Independent, voted for Biden, but I'm concerned with language that leans towards criminalizing Republicans or the party as a whole. Dave says our country is better with multiple viewpoints and Democrats need to remember that their way of thinking is not the quote "right way." It is just one perspective.

Laura Knoy: Dave, thank you for writing in. And, Congressman, it makes me wonder, how can you - because all you can control is your own behavior - how can you comport yourself in this difficult time to try to bring the people of New Hampshire together? The people of your district, which is a more moderate district, has gone back and forth between Republicans and Democrats. How can you comport yourself in the days ahead in a way that might encourage people to dial it back a little bit and listen to each other?

Chris Pappas: Well, there's no doubt we have a long list of issues that we have to address, including and especially this pandemic and economic crisis that we're experiencing right now. And we know the only way forward is by finding ways to work together. I remember the way we got another COVID relief bill done was by members of both parties coming together and insisting that their leadership bring a bill to the floor. And that's exactly what happened. So I think the power center in Congress is still with those who are solutions oriented. And I think that's exactly where it needs to be moving forward, if we're going to have a shot at saving lives and getting more resources out to our communities and scaling up a national vaccination effort in a more effective way. So that's where our focus needs to be. And I think if we can safely get through the inauguration on the 20th, I think there's a lot of healing that can happen. We have to commit ourselves to this. What we saw happen yesterday at the Capitol with the impeachment of a president was not about politics. In fact, it was very far from that. It was about accountability. It was about making sure that we took advantage of a process to say what the president did was wrong and about moving forward. And I think that was the first step in a process that involves all of us to dial back the rhetoric, lower the temperature and find ways to work together. That was the message people sent in November, by the way, and that's why Joe Biden won his election. And I think that's exactly the type of culture he's going to create in Washington and leadership that he'll provide.

Laura Knoy: Well, Dave, thanks for writing. And Congressman Pappas, I know you have limited time with us today, so I'll let you go. We'll talk to you again. Thank you very much.

Chris Pappas: Thanks, Laura. Take care.

Laura Knoy: That's New Hampshire First District Congressman Chris Pappas, he's a Democrat from Manchester.

Laura Knoy: Well, coming up, we return to law professor Brian Kalt and more of your questions about impeachment and other presidential accountability measures that we've talked about. So stay with us. This is the Exchange on New Hampshire Public Radio.

Laura Knoy: This is the Exchange, I'm Laura Knoy. This hour, we're following up on the impeachment vote at the U.S. House yesterday and getting your reaction. Helping us out, as Brian Kalt, he's a professor at Michigan State University, a scholar of constitutional law and the history of the presidency. He's written two books on what the Constitution says about holding presidents accountable. And Professor Kalt, let's go right back to our listeners.

Laura Knoy: And Jeff is calling in from Nashua. Hi, Jeff. You're on the Exchange. Go ahead.

Caller: Thank you, Laura. Thank you for having me on board. I have a comment concerning whether or not a president or a sitting president can pardon himself. I'm very, very uncomfortable with that.

Caller: And the reason for that is I find that if a president, say President Trump for example, if he finds out that he can pardon himself, that could set for a rather a very, very dangerous situation in the future of this country. Where future presidents come in. If they feel that this president can pardon himself, they're going to get the attitude that, hey, I can do anything I want no matter what happened, because all I can do is just say so and I can get off the hook. So that could really, that could be very dangerous in the future for this country. And I'm kinda wondering.

Laura Knoy: Well, Jeff, thanks for calling. Sure. And we talked about this before, Professor Kalt. It's a little bit murky, isn't it?

Brian Kalt: It is, but I think it's important to note that even if a president could pardon himself, that doesn't mean that it would free him from any possible consequence. So, first of all, there's still state criminal liability. He wouldn't be able to do anything about that. Second, he would be subject to impeachment. And even if you wait until the end of his term, as we're about to see, you can impeach a president even after that. And then the self-pardon itself might be part of a criminal act of obstruction of justice. It might be part of a conspiracy. So the pardon might be effective, but it also might itself expose him to criminal liability that the pardon wouldn't cover because pardons only cover things you already did. So you can't pardon yourself for pardoning yourself.

Laura Knoy: Here's another question, and this came up with our conversation with Congressman Pappas. What about members of Congress who might have been involved in planning this attack? Again, this is only a charge. This is under investigation. But Professor Kalt, if lawmakers are discovered to have helped with this, what's the punishment for them?

Brian Kalt: The Constitution provides a mechanism called expulsion, so if it's in the House, the House of votes in the Senate, the Senate would vote and they need two thirds they can expel. If they get a two thirds vote, they can expel for whatever reason. There's also the possibility of the 14th Amendment, Section three, as we talked about before. That's a little less clear how that would play out. But expulsion is definitely there is as a remedy.

Laura Knoy: Ok, let's take another call. And this is David in Enfield. Hi, David. Thanks for calling in today.

Caller: You're very welcome. I'm glad you got the professor back on. I had, I haven't heard the 25th Amendment really explained in full on any of the media. And I think I understand it. But I'd like maybe the professor to givea, you know, just a full picture of what it is. And also, I was wondering what he thought about what I've heard talk in Congress about a about, quote, "reining in the media" and creating a panel commission or something that would somehow act when there was misinformation being put out.

Laura Knoy: Well, David, I'm going to let you go just in the interest of time, but on the media question, we're going to be looking at that a lot on other shows. So we're going to set that aside for now.

Laura Knoy: And to our guests expertise, though, the 25th Amendment and Professor Kalt, we talked about this before, but it is complicated. So could you just give Dave just a little more clarity, ABC on that?

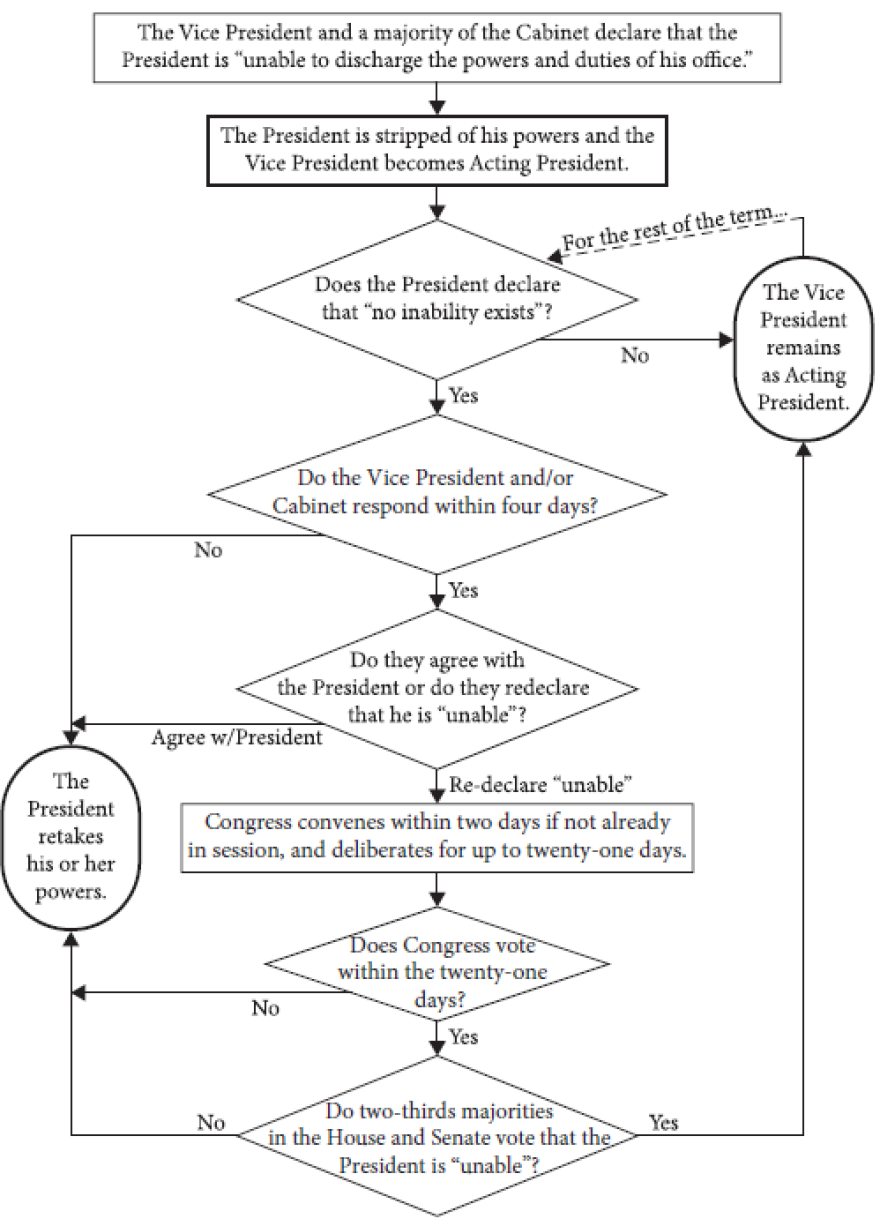

Brian Kalt: Sure, so I'll sort of talk through the flowchart here. Ordinarily, if the president is incapacitated, vice president, majority of the Cabinet send their declaration that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office to to the Hill. And then the vice president becomes acting president. When and if the president says that he's better or says that he never was unable, he sends a declaration. He, this is important, he does not take power back immediately at that point under Section four. He has to wait. There's a process and the process is the vice president and cabinet have four days to reassert that the president is unable and the vice president is in charge during that time. If they say that he is unable, then that dispute goes to Congress. Congress has, they have to assemble. If they're in recess, then they have 21 days to debate it. They don't have to take all 21 days. They could vote right away. But unless the president loses two thirds in the House and two thirds in the Senate, he takes power back again. The vice president is in charge in the meantime, which is why they'd be able to run out the clock.

Brian Kalt: It wouldn't have to vote before the 20th if it were invoked today. But if, say, the Senate voted on day one and they didn't get two thirds agreeing that the president was unable, he would take power back immediately. So for a president to be kept out, if he says that he's okay, you would need the vice president and the Cabinet and two thirds of the House and two thirds of the Senate to disagree. So it's really about presidents who who are incapacitated, not presidents doing bad things because if presidents are doing bad things then you just impeach and convict. You only need a simple majority in the House for that. And you don't need the vice president and Cabinet. It's important to to see that this limit here is to protect the president. When the president says he's okay, Section four protects the president and the vice president and Cabinet are the ones who make that first call, not people who already wanted him gone.

Laura Knoy: Well, in your question, David shows, you know, our listeners have a lot of interest in this 25th Amendment. So if people want to see that flow chart that Professor Kalt has put together and it really lays it out nicely how this mechanism works, we'll put it on our website.

Laura Knoy: One more question for you, Professor Kalt. Here's this from an email that did not give his or her name. The professor has repeatedly said so many aspects of this scenario are legally unclear. This person asks, do you think this will become a learning example whereby follow up legal clarification will happen? It's a great question and one I want to ask you, too, Professor, some new material from this whole episode for your next book or your next classes.

Brian Kalt: In my book at the end of each chapter, self-pardons, prosecuting presidents, 25th Amendment, late impeachment. I have a section where I say, well, what can we do about this? How can we clarify it? And there are things that can be done. So just saying, oh, we can amend the Constitution. That's not usually we have the hardest Constitution in the world to amend. So that's kind of a blithe conclusion that I don't think works. But there are things, there's legislation that could be passed to clarify, there's statements that presidents or their lawyers could make in quieter times that would clear these things up, that would settle them so that we all know in advance what the standards are and can play according to those rules.

Laura Knoy: Wow. Well, Professor Kalt, it's been really nice to talk to you today. Thank you very much for being with us.

Brian Kalt: Well, thanks so much for having me.

Laura Knoy: That's law professor Brian Kalt of Michigan State University. He's written two books, what the Constitution says about punishing presidents. They are called Unable - that's about the 25th Amendment, which we talked a lot about today - the other one is called Constitutional Cliffhangers: A Legal Guide for Presidents and Their Enemies.