From the time he was born until the age of three, IsakMcCune of Goffstown was a healthy, smart, sweet little boy.

And then his mother says her little boy just changed. He started having tantrums. Really big ones.

"We called it being held hostage," says Robin McCune. "He would go on and on for hours. We couldn’t leave the house. And then when they finally got to the point where he was just exhausted, then he would come to me and be held. Most of them were four to six hours. They were long."

In the home video below, Isak is fishing a quarter out of a car seat. It’s summer. He’s hot and sweating - and he will not get out of the car.

There are children who go from being healthy one day, to suffering from crippling obsessive behaviors the next day. And a controversial scientific theory says those behaviors are caused by one of the most common childhood ailments: strep throat.

In New Hampshire, families fight an uphill battle tracking down a doctor to diagnosis their sick child with this poorly understood illness.

Peeling 'The Onion'

As each week revealed new symptoms, Robin McCune says they began to call their once happy little boy "the onion" - obsessive behaviors morphed into intrusive thoughts, then to tics and attachments issues.

Mental health specialists diagnosed Isak with oppositional defiance disorder - but that mostly hits older children, not three year olds. Obsessive compulsive disorder made sense; but OCD doesn't just hit overnight.

In fact, Isak's problem was medical. It would take three years for the McCunes to bring their son back from wherever it was he was trapped.

"I think imprisonment or possession is an ideal term," says Dr. Sue Swedo at the National Institute of Mental Health. "And you can imagine that if this was the Middle Ages these children would be subject to exorcisms and other things to try and get the, quote, demons out of them."

Swedo is the leading scientist on a condition she first observed in the 1980s. It’s called PANDAS – Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections.A 'Mind-Boggling' Connection

So, how could strep do this?

Strep is an ancient bacteria, and one of the reasons it have been around so long is it's good at hiding: strep camouflages against the throat by creating proteins that look like the body’s own tissue. So it takes the immune system time to find the infection – and when it does, the body kills the strep with antibodies.

But in PANDAS, the antibodies then keep fishing for strep – and they attack the body's own proteins that look like the ones the strep had mimicked.

If the antibodies find those proteins in the heart valves, that leads to rheumatic fever. If they attack a part of the brain called the basal ganglia - the theory goes - that leads to PANDAS.

"The thought that you could actually present with symptoms of anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder and movement abnormalities was a little bit mind boggling, frankly," says Swedo.

One study found as many as 10 percent of children with OCD and tic disorders may have it because of strep antibodies: but even the science behind that is speculative.

A Medical Mystery - Or Controversy?

Swedo’s case is a tough sell to some in the medical community. After all: most kids get strep every year.

And here’s what makes it harder to believe: PANDAS is a medical condition, but the diagnosis is through clinical observations.

"You know you reach a point where you’re willing to believe things that may not be scientifically correct," says Dr. Harvey Singer, a pediatric neurologist at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore.

Even though Singer initially published papers supporting the strep-PANDAS connection, he now says there is no definitive link.

"The thought that you could actually present with symptoms of anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder and movement abnormalities was a little bit mind boggling, frankly."

"And all we’re charging the physicians with is, look, you guys have a responsibility to prove what you’re doing," says. Dr. Singer.

PANDAS has become Swedo's professional - and personal - mission. She admires Dr. Barry Marshall, the Australian doctor who proved Helicobacter pylori causes ulcers. Other doctors didn’t believe him. So Dr. Marshall drank the bacteria in a broth, and gave himself a nasty ulcer - definitively proving his point to the medical community.

Dr. Swedo says "it would be just absolutely fabulous" if she could give herself PANDAS.

"But I can’t so I’ve done the next best thing. I’ve studied hundreds and hundreds of children and now have colleagues at 12 sites across the United States and in five different countries."

Those colleagues have followed children with dormant PANDAS and found their symptoms spike when the child is exposed to a strep infection.

Families Lost In The Middle

Many in the medical community remain split on whether or not PANDAS actually exists. Other doctors have never even heard of it.

Meanwhile, families get lost in the middle, searching for a treatment for their kids.

The Nichols family lives in Keene. They have twin daughters who both got sick with PANDAS in the summer after finishing the eighth grade with high honors. They have both been hospitalized dozens of times - sometimes in two different states at the same time - for paralyzing anxiety and anorexia.

The Nichols girls at times have gone days without drinking water - for fear of calories.

"We have done everything in traditional medicine for the last two years," says Emily Nichols, the twins' mother. "We’ve done tough love. We’ve done just love."

"We have done everything in traditional medicine for the last two years. We’ve done tough love. We’ve done just love."

Last fall, Taylor Nichols was stuck in Cheshire Medical Center's ER for 11 days, waiting for a psychiatric hospital bed to open up.

"She’s got an eating disorder so the psych units won’t take her," Emily said at the time. "And because she’s got psych issues, the eating disorder units won’t take her."

Like Isak’s family, the Nichols learned about PANDAS from their own research; then they sought out a doctor who treats it. But the Nichols twins got much sicker than Isak ever did. Antibiotics and steroids can keep most PANDAS cases at bay. Not Taylor and Kirsten.

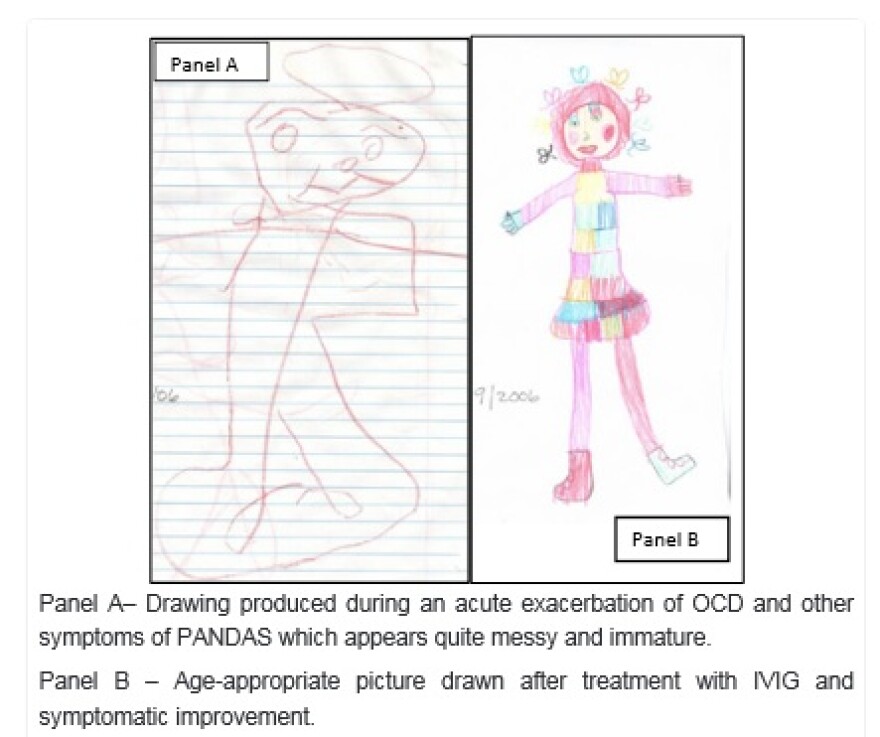

So once Taylor finally got a bed at New Hampshire Hospital, Emily and her husband made a big choice for their other daughter. They put Kirsten on an infusion of a human protein called IVIG – it’s like a reset button for an out-of-whack immune system, used only for extreme PANDAS cases.

Emily says Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois, their family's insurance company, said the drug was too experimental and denied the coverage. In response to an NHPR inquiry, BCBS of Illinois did not say why the request was denied.

So the Nichols put the drug on their credit card. It cost $17,000.

Two months later, it seems to be working.

"I guess I didn’t realize how irrational some of my thinking was," Kirsten says. "Like my fear of water. That wasn’t going to harm me in any way."

"Time Is Telling"

Dr. Richard Morse, a pediatric neurologist at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, says about 70 percent of the kids he treats for PANDAS respond with antibiotics or steroids. Many of the others respond to IVIG and other more invasive treatments.

As further proof in the case of PANDAS, Morse points to the widening body of literature on autoimmune diseases impacting the brain.

Still, Morse says he respects the skepticism. In fact, he says, his colleagues at Dartmouth are split on the disorder. But he also says PANDAS is only now stepping out of the fringes of scientific understanding - and that is always a messy process.

"As science advances and as our knowledge increases, we come to the areas that are uncertain and incomplete," says Dr. Morse. "It usually lurches forward by vigorous debate and people taking strong positions of belief that they’re right. And ultimately time will tell. I think in the case of PANDAS time is telling."

Although big questions are unanswered. It seems children can outgrow PANDAS, but we don’t know why. There are no FDA-approved treatments, yet Swedo’s team is researching drugs like IVIG.

Antibiotics worked for Isak.

Lost And Found

After three years, the McCunes found a doctor in Boston who diagnosed Isak with PANDAS. After a round of antibiotics, he got healthy as quickly as he'd fallen ill.

When I met him, he was running around the house and showing off his Transformers.

Isak is still subject to flairs of his prior symptoms if strep goes around in school. Last fall the McCunes organized a first-of-its-kind PANDAS conference in New Hampshire.

The Nichols, however, are still in limbo.

Kirsten is back in school, but after three months at New Hampshire Hospital, Taylor is home. She’ll get her IVIG later this week.

This time, insurance will cover it.