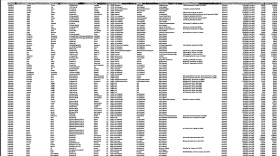

With the 2012 primary less than three weeks away, candidates for state office in New Hampshire have until midnight Wednesday to file their first campaign finance reports with the Secretary of State's office.

The reports list donations from individual supporters, as well as contributions from political action committees, state and national political parties, lobbying groups and corporations.

Hundreds of seats are up for grabs across the state, but most of the attention, and money, is focused on the race for governor. The leading candidates — Republicans Ovide Lamontagne and Kevin Smith and Democrats Jackie Cilley and Maggie Hassan — have been campaigning for months, and their financial reports will be an important indicator of their support leading up to the September 11 primary.

But if the past is any guide, the disclosures will offer a rather limited view of how political campaigns are paid for in New Hampshire. Critics say flaws in the state election statutes make it easy for corporations and other wealthy donors to exceed dollar limits on individual contributions, putting the integrity of the state's political process at risk.

One loophole allows the owner of multiple limited-liability corporations to make donations up to the legal limit — $7,000 per election cycle — on behalf of each LLC. In 2010, one gubernatorial candidate appeared to benefit from more than $20,000 in donations from a single Dunkin' Donuts franchise holder, who made contributions on behalf of 18 different LLC's.

A more glaring loophole allows non-profit "social welfare" organizations to raise and spend unlimited amounts from anonymous donors for so-called independent expenditures. According to an analysis by the Concord-based Coalition for Open Democracy, of the more $3.5 million tax-exempt groups poured into the 2010 races for governor, state Senate and Executive Council, less than $60,000 was disclosed with the Secretary of State's Office.

In the wake of the 2010 Supreme Court ruling in the Citizen's United case, some states have tried to reign in independent expenditures by requiring groups known as 501(C) operations to disclose their political activities. But repeated efforts to strengthen those requirements in New Hampshire have failed to gain the necessary legislative support.

"The statute is a mess and really needs a complete overhaul," says Olivia Zink, program director for the coalition, which advocates for public financing of elections. "It's hard for the average voter to to know who is bankrolling our elections."

LOOPHOLES IN THE LAW

Earlier this year, the State Integrity Investigation, a collaborative project of the Center for Public Integrity, Public Radio International and Global Integrity, analyzed the corruption risk in all 50 states using 330 specific measures, including how well each state regulated the financing of political campaigns.

Citing the loopholes in the state's election laws, the project awarded New Hampshire a D for political financing. That came as little surprise to Kathy Sullivan, the former chair of the New Hampshire Democratic Party.

"There's a lot of money coming into the state," she says, "but there's little will on the part of the legislature to do anything about it."

Sullivan's anger over the political influence of secretive nonprofit groups was shared by her Republican counterparts during the 2010 gubernatorial race. In the thick of the campaign, the state parties accused each other of sanctioning attack ads funded by independent expenditures.

Democrats asked the state Attorney General's office to investigate two campaigns aimed at incumbent John Lynch — one funded by Americans for Prosperity, the other by the National Organization for Marriage. Republicans took issue with a video produced by Citizens for Strength and Security, whose donors include the Democratic Governors Association and several labor unions.

Both complaints revolved around what constitutes a "political committee," which state law defines as any organization of two or more persons seeking to influence elections or ballot measures. In New Hampshire, political committees are required to register and file periodic campaign finance reports that identify their contributors.

But, in a ruling on Sullivan's complaint, the attorney general said there was no evidence that the "stated purposes" of AFP and NOM were to support or oppose a candidate. Therefore neither organization qualified as a political committee under state law.

In 2010, several months before filing her complaint, Sullivan worked with attorney Paul Twomey to come up with a bill for the legislature that would have changed the state's definition of a political committee. The measure called for 501(C) groups that spend at least $10,000 on “messages, parties or candidates” to register with the Secretary of State's office.

Sullivan admits she was surprised when an "an odd coalition" of right- and left-leaning organizations joined forces to help defeat the bill.

"Frankly none of these groups wanted to disclose who their donors are," Sullivan recalls. "Someone could put a million bucks into an election in New Hampshire with the purpose of electing or defeating a candidate, and the voters will have no idea who that person is."

Olivia Zink, of the Coalition for Open Democracy, says her organization has aggressively lobbied in support of several bills similar to the one in 2010. The most recent, during the 2012 session, would have required any group that spends $5,000 in a calendar year to influence an election to register as a political committee and file disclosure reports with the state.

Zink said the bill didn’t go anywhere.

"With 400 members in the House, many of them get elected by putting their names on the ballot and spending very little money," Zink says. "A lot of them don't understand the complexity of our election laws."

MONEY MATTERS

Former New Hampshire Republican Party chair Fergus Cullen agrees that independent expenditures are a problem in state elections. But he doesn't think requiring greater disclosure from groups that rise and spend them is the answer.

The better solution, he says, would be to eliminate the cap on individual campaign contributions. Cullen maintains that the donor limits are not only confusing, but they essentially compel candidates to rely on third-party groups willing to inject huge amounts of money into important races.

Candidates for high-level office in New Hampshire typically begin raising money well before they officially file paperwork to be included on the ballot. This "pre-declaratory" status allows them to collect as much as $5,000 from each individual donor.

However, once they've filed as an official candidate, they're limited to $1,000 in individual contributions, plus another $1,000 if they go on to the general election. Cullen says this makes it harder for candidates to raise money when they need it most, down the stretch.

"Most individuals want to wait until the election (to contribute), but at that point they can only give $1,000," Cullen says. "Candidates can't raise enough money to campaign when the cap is $1,000."

That, in turn, forces many late-breaking donors to contribute to groups that aren't connected to a particular candidate and fall outside the state's disclosure requirements. "At that point, all of the incentives are to give to a PAC or a 501c4," Cullen says.

Cullen and Zink may not agree on the solution to independent expenditures in New Hampshire elections, but they see eye-to-eye on the potential impact of such spending on the 2012 races. Both say spending by nonprofit advocacy groups will almost certainly exceed the money raised and spent by the candidates themselves.

Wayne Lesperance, a political science professor at New England College in Henniker, says every state is grappling with the implications of independent expenditures in the post-Citizen's United era. But the problem is particularly acute in New Hampshire, due to its "first in the nation" presidential primary.

That unique status attracts more attention from wealthy donors looking to affect the outcome of state elections, Lesperance says, while making electoral reforms that much more difficult.

"The money coming in from outside of New Hampshire is something other states probably don't have to deal with," Lesperance says. "That's an incentive to make spending as easy as possible, and to make the laws around disclosure not as aggressive as perhaps it should be. Because no one wants to discourage that money coming in if they think they can benefit from it."