The southern tier of the state is getting its first dusting of snow of the winter season this morning. As it does, the first question on the minds of many is probably “how is the driving?”

We have never been better at keeping roads clear during snow-storms, but now for environmental and budgetary reasons the question is how to use less salt.

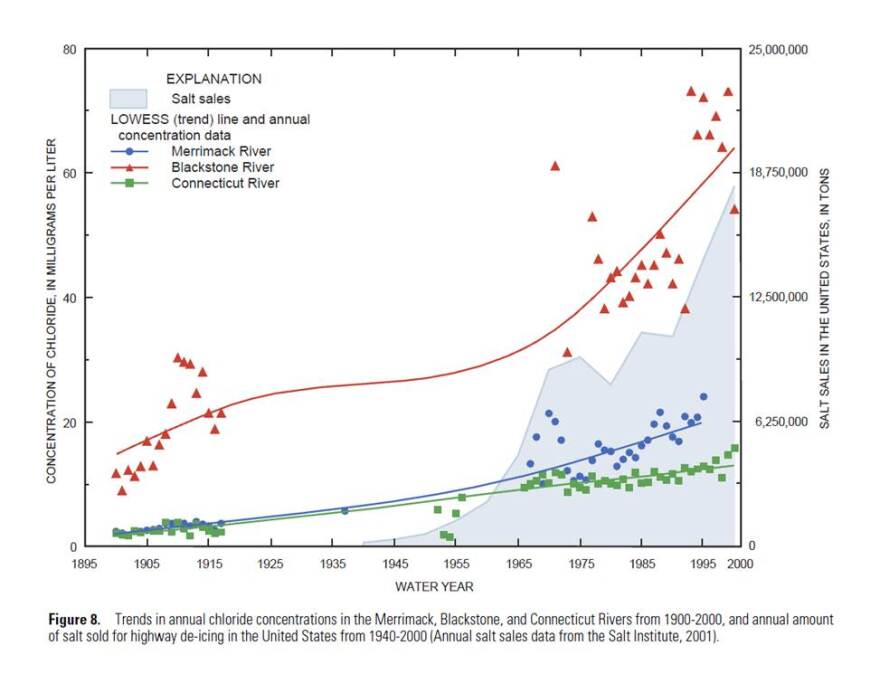

The amount of salt going into New Hampshire’s rivers has been rising since the sixties. Mostly, this is because the amount of pavement is rising, but also it’s because drivers these days expect wet, black pavement, and they want it fast. The problem now is so much salt is going into some brooks around the state that it’s toxic.

“We need to reduce the amount of salt in these watersheds by anywhere from 25 to 45 percent, which is a fairly tall order,” said Eric Williams, with the Department of Environmental Services, at a recent Salt Symposium, convened in Windham.

Big Projects, Big Reductions

One big motivation for the state to reduce salt is to widen i-93, under the Federal Clean Water Act, and when it first reached out to snow and ice professionals with this proposition, it faced an uphill battle.

“We were very hesitant to get involved, because when they first came in the first approach was more like, ‘You need to cut back on how much salt you use because we need to widen 93 and right now we’re being stopped from widening it,’” says Alan Cote, who works for Derry’s Public works department.

For years, now the state has been reaching out to plow truck drivers, parking lot owners, and municipal public works directors. As is often the case with these things, it took some time to get people like Cote on board.

“I think I probably said something to the effect that the yellow perch in Beaver Brook were not as valuable to me as the residents of the town of Derry,” he says.

Many of these folks have since come around, in part because they were convinced they could use less salt and still preserve safety, but also because it saves money. Salt is still cheaper than most alternatives, but especially in recent years it has been getting more expensive.

In general, state and municipal plowing has made great strides in reducing salt use. Under Cote’s watch, Derry has added more than 35 miles of paved roadways, but reduced its salt use by 25 percent.

The reductions come from a number of methods. Spreaders can mix salt with water to form brine, which makes it work better. They can pre-treat roads with brine before a snowfall, which is like greasing a pan and makes the snow easier to plow off. They can even buy fancy additives to make a little salt go further.

Matthew Scott from New Hampshire Ice Melt claims his chemical, which is a by-product from a vodka distillery in Hungary, is the best out there but acknowledges there are many others.

“There’s a beet-juice product that comes out of the Midwest, there are some other companies that use molasses to try to make it sticky to stick to the salt,” he says.

Protection For Private Spreaders

But roads are only part of the problem. Most of the salt in many watersheds is coming from parking lots maintained by private companies.

Those companies – unlike the state and local government – can be liable if someone slips and falls in their parking lot.

That is until recently, when the Republican President of New Hampshire’s Senate, Chuck Morse, guided a bill through the statehouse that gave these folks some protection.

“I think it equates a lot to the ski industry to be honest with you,” he says.

If you crash while skiing, you don’t sue the ski area unless it was grossly negligent: like not putting up a flag if there’s a crevasse. The new law does much the same for parking lot owners.

“If people will follow our instructions of how to apply salt, like our own DOT does, we will give them the liability protection much like the ski industry has,” says Morse.

There is some grey area here: how do you define due-diligence in terms of clearing a parking lot?

That’s where Raqib Omer comes in, a researcher from the University of Waterloo in Ontario, who originally hails from India. This makes him somewhat of an oddity in a room full of plow truck drivers, and he often jokes about it.

“I’ll be very honest with you, this is a tough crowd,” he says, “Often when I go and present I’d be the only person in the crowd who is brown.”

He’s gathering data from all over North America from different snow-storms and different types of surfaces, in order to define how much salt is just enough. The data is reported automatically from mobile phone apps and smart salt spreaders.

“It’s not just university numbers, but real data provided to us by real businesses, real contractors, real snow and ice professionals,” he emphasizes.

Putting some science to this tricky question: how little salt can we use, and still keep people safe.