This story was originally produced by the New Hampshire Bulletin, an independent local newsroom that allows NHPR and other outlets to republish its reporting.

This is the second in a three-part series on New Hampshire’s intellectual and developmental disability care system. You can read Part I here, and Part III will be published on Friday.

They call it the disability cliff.

When young people with intellectual and developmental disabilities finish high school, they lose access to the extensive services provided by public school special education programs. Most parents work, and while that allows them to help support their adult children financially, their absence creates a care void that is not easy to fill.

Over many months, the Bulletin has explored abuse and neglect in New Hampshire’s intellectual and developmental disability system through court filings, law enforcement documents, state records, and conversations with lawyers, advocates, and family members. Breakdowns in care in recent years have led to many instances of preventable harm — sometimes fatal harm — and left in their wake devastated families who wanted only to give their children opportunities for a good life but found tragedy instead.

Those tragedies often begin at the precarious edge of the disability cliff — and that was the case for the Weidlich family.

‘Looking for a body’

When Stephen “Stevie” Weidlich Jr. aged out of high school in 2017 at Crotched Mountain School for Students with Disabilities in Greenfield, his father, Stephen Weidlich Sr., saw few options.

Weidlich worked full time and Stevie’s mother wasn’t involved in his life. He considered trying to get designated by the state as an in-home care provider of state services, which would have allowed him to receive some Medicaid funding as Stevie’s caregiver. Such arrangements typically cost the government a fraction of what placement in a residential facility costs.

However, the family felt discouraged about pursuing that path when an employee of PathWays of the River Valley, one of 10 agencies designated by the state Department of Health and Human Services’ Bureau of Developmental Services to coordinate care for people with disabilities, stopped responding to their inquiries on the matter, Weidlich said in a recent interview.

The one option that remained was to place Stevie in a home run by PathWays with a live-in caregiver, a service people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are legally entitled to receive through Medicaid and other state and federal dollars.

Within a few years, Stevie would become a casualty of that system. In December 2022, police knocked on the Weidlich family’s door in Unity to tell them Stevie’s body had been found in the woods behind the home of his caregiver.

At the time of his death, Stevie, 26, was living in Allenstown with PathWays employee Douglas Onkundi.

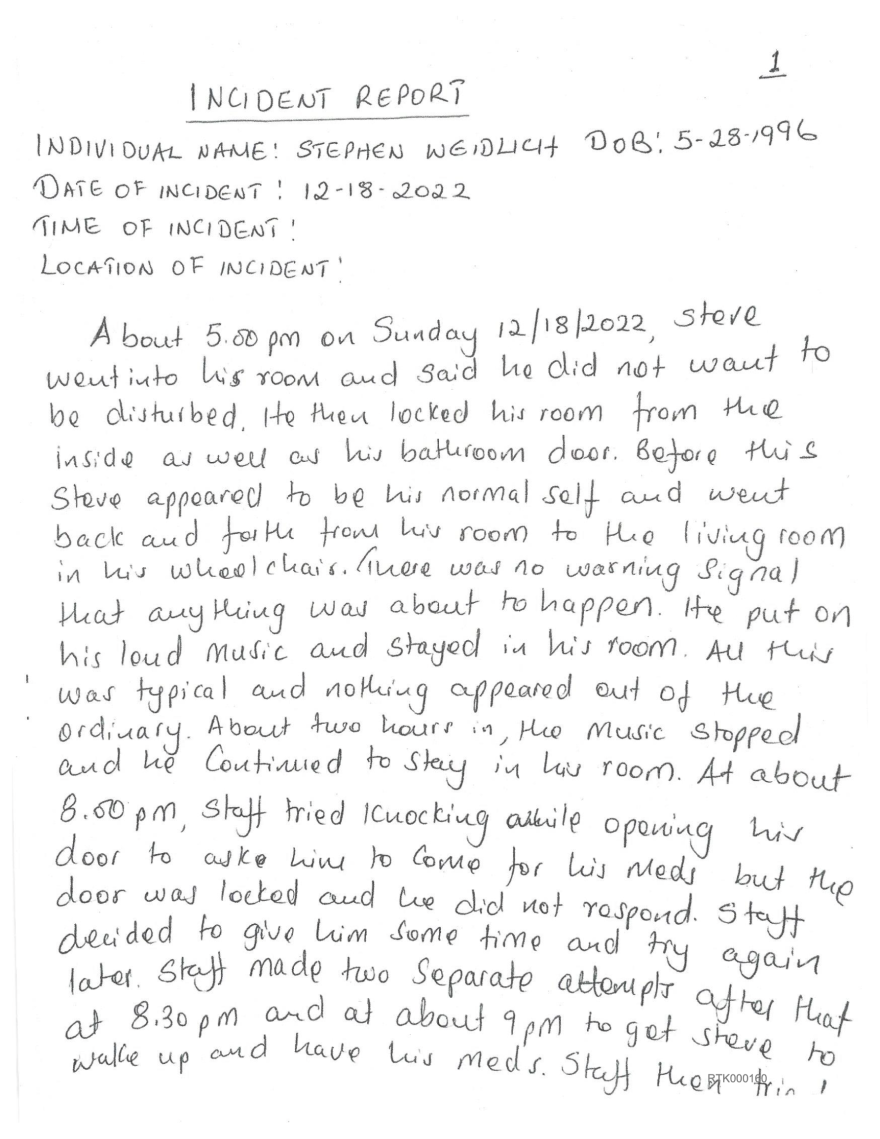

As a live-in caregiver, it was Onkundi’s responsibility to ensure Stevie, who had physical, developmental, and intellectual disabilities, was given 24/7 care. However, according to documents from a state investigation obtained and being made public for the first time by the Bulletin, Onkundi wasn’t actually living in the home at the time of Stevie’s death. He told police he was living in Manchester, and would return to Allenstown to give Stevie his medications. In his stead, investigators learned, Onkundi was paying another man to live in the home and care for Stevie with part of his PathWays paycheck and pocketing the rest. The man had no formal training and was not officially authorized by Pathways or Stevie’s family. Neither Onkundi nor the other man were criminally charged.

In conversations with state investigators, PathWays managers said they’d told Onkundi on multiple occasions only trained staff can work with the people in their care. However, according to the report, Onkundi said there was “an unwritten rule that everything was OK unless PathWays said otherwise.”

On Dec. 18, 2022, security camera footage from a neighbor shows Onkundi leaving the home in the morning and returning around 8 p.m. the day Stevie died, per the report.

Investigators were told Stevie had locked himself in the bedroom and that when Onkundi returned, he used a ladder to climb up to the window and discovered the glass was broken and Stevie was gone. Onkundi told state investigators he searched for Stevie, who had a history of fleeing, before calling police.

It was too late. A police dog found Stevie’s body in the woods behind the home. There was evidence of hypothermia and a blunt force injury to Stevie’s ribs consistent with either a fall or a blow to the chest, the police report said. It was a cold night with snow on the ground.

Weidlich said Onkundi called him after the death and what he said infuriated him even more.

“Stevie was not mobile,” he said. “He was in a wheelchair. He can only crawl. (Onkundi) told me when he noticed Stevie was gone, he got in his car and drove around looking for Stevie. How does that make any f—ing sense?”

Onkundi told him they were looking for “the body.”

“You were looking for a body or you were looking for Stevie?” he said. “Obviously, if you were looking for a body, what does that say? You weren’t looking for a live person.”

‘Daddy, I can’t see’

Stevie was born in Long Island, New York, in 1996 and spent his early childhood there. Weidlich said Stevie had “an awesome sense of humor,” and the whole family remembers him as fun-loving and a jokester. He was 9 years old when his disabilities began to emerge.

“One day, I’m getting ready to go to work,” Weidlich said. “And he comes down from upstairs holding onto the wall. He goes, ‘Daddy, I can’t see.’ And I’m looking at him, and he’s got one eye at me and one eye off.”

The family rushed Stevie to the hospital, where they learned he had a type of growth called a cavernous malformation inside his brainstem. He had emergency brain surgery the next day to remove the growth.

The surgery was successful, but it affected Stevie’s equilibrium and required him to start using a wheelchair.

In 2006, the family relocated to Unity, New Hampshire, where Weidlich’s father lived. Stevie had been “falling between the cracks with school,” Weidlich said, and his wife was struggling with an opioid addiction.

“I decided to fall back, regroup, put my wife in rehab, and we found this place,” he said. “I moved everybody up here.”

In New Hampshire, Stevie was able to regain the ability to walk without a wheelchair through rehabilitation services. However, about a year later he started losing his balance again, so the Weidlichs brought him to Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, where doctors discovered the growth was returning. The family brought Stevie back to New York for a second surgery in 2010. This time, doctors clipped a nerve.

“So he went into it being able to walk,” Weidlich said. “And came out of it not being able to walk anymore.”

Stevie was diagnosed with mild intellectual and developmental disabilities, and he began having behavioral issues.

“The second surgery affected him much more,” Weidlich said. “He’d have anger issues, and he’d just be frustrated.”

After Stevie left Crotched Mountain in 2017, PathWays placed him with a live-in caretaker named Prashanna Sangroula. Weidlich’s work schedule made him unable to give his son the 24/7 care he required, so PathWays provided residential care. Stevie and several others with disabilities lived happily in a house with Sangroula and Sangroula’s family. The young man would come home to Unity every other weekend and on holidays. The family loved Sangroula.

When the Sangroulas moved to Virginia, however, PathWays needed to find a new live-in caregiver. With Stevie’s behavioral issues and need for constant supervision, Weidlich said he was under no illusions about just how challenging that would be.

For a while, Stevie bounced among temporary caretakers until PathWays found him a more permanent home with Onkundi in Allenstown in October 2021.

‘A lack of consequences’

The state investigation from the Bureau of Adult and Aging Services concluded that Onkundi had committed neglect. However, the bureau didn’t finalize that finding until November 2024, nearly two years after Stevie’s death. Onkundi is now legally ineligible to be a caregiver of people with disabilities, but in the nearly two years between Stevie’s death and that finding, he would’ve been legally permitted to work for PathWays or another agency. It’s unclear whether he did so. Onkundi did not answer the Bulletin’s phone calls, voicemails, or text messages.

PathWays didn’t respond to the Bulletin’s requests for an interview or comment.

No criminal charges have been filed against Onkundi and the Attorney General’s Office concluded its investigation into Onkundi, the office told the Bulletin. The case has been kicked back down to the Allenstown Police Department, which doesn’t have legal authority to file manslaughter or murder charges but does have authority for lesser offenses. The Attorney General’s Office refused to answer the Bulletin’s questions about the case because the investigation is ongoing at the local level.

“Investigations of this nature can take time and may move between local law enforcement, county prosecutors, and this office depending on the circumstances,” Michael Garrity, director of communications for the Department of Justice, wrote in an email. “Investigating agencies cannot rush to judgment, but follow the evidence and the facts wherever they lead. Any prosecution must be supported by proof beyond a reasonable doubt. That standard is imposed on us by the law and professional ethics.”

Weidlich and Stevie’s stepmother, Crystal, now feel left in the dark.

When he learned there would be no murder or manslaughter charges, Weidlich was angry. Allenstown police seemed serious about the investigation and kept them updated early on, he said, but as the attorney general got involved and time passed, they heard less and less. Still, he’s holding out hope that Allenstown police will file some sort of charges.

In the meantime, Weidlich has filed a lawsuit against PathWays and Onkundi, among others.

There were other apparent lapses in oversight, too.

The Incapacitated and Vulnerable Adult Fatality Review Committee is a board of experts established through state law to review concerning deaths of vulnerable or incapacitated people, evaluating if there were any failures in state policy or practices that led to the death. The board then makes recommendations on how to prevent future similar deaths.

Both co-chairs of that committee, Vanessa Blais and Francesca Broderick, told the Bulletin Stevie’s death was never brought before the committee. Agencies like the Bureau of Aging and Adult Services and Department of Health and Human Services — which both knew of the death and have representatives on the committee — aren’t legally obligated to report deaths to the committee. They’re merely encouraged. Still, when the Bulletin told her about Stevie’s death, Blais said she was shocked it hadn’t been brought to her committee.

Attorneys Kristin Ross and Cristina Rousseau, who are representing Weidlich in his lawsuit and have represented multiple families in this system, said tragedies like Stevie’s are symptomatic of a broken system.

“Really what we see is a lack of accountability and a lack of consequences when things go wrong within the area agency system, and frankly I think that starts at the top,” Ross said. “There are regulations that are supposed to be being followed, but what we find is they’re not, and there’s no consequences, and there’s a very laissez-faire attitude about the fact that they’re not being followed.”

Cristina Rousseau In Stevie’s case, Rousseau noted the entire investigation focused on Onkundi.

“But you know what has never happened in any of the cases we’ve been involved (with)?” Rousseau said. “The area agencies are not investigated. They are the ones that have all of these duties, and when it comes to violations that have occurred, nobody looks at PathWays.”

Rousseau and Ross also point to what they consider a perverse financial incentive within the system of care.

“Something that we’ve seen is a pushback against allowing immediate family members to become the approved in-home care providers,” Ross said. “And instead a push towards individuals outside of the family.”

Agencies and caregivers earn significantly more money providing residential care than day services. According to PathWays’ contract with Onkundi, acquired by the Bulletin, Onkundi was paid more than $5,000 per month and more than $62,000 annually to care for Stevie. Had he been providing day services, he would’ve been paid about $1,400 a month and $17,000 annually, according to the contract.

“Everyone is always so concerned about waste, fraud, and abuse,” Ross said. “We are literally giving the state evidence of waste, fraud, and abuse within our very own state agency system, and nobody’s doing anything about it.”

Rousseau said the absence of state action is perplexing.

“You would think that somebody in the state would maybe want to take a look at this,” she said. “But they don’t even look at it. They just continue to pay and engage and give contracts to these area agencies after these issues have come to light. … The fact a civil lawsuit ends up being the vehicle to get answers for a family whose son died and froze to death in the care of somebody approved by the state tells me we are dealing with an incredibly broken, broken system.”

Before Stevie went to live with Onkundi, he told a case manager some of his hopes for the future, all of which were outlined in the service agreement as things for him to work toward with the help of his care team. He wanted a job, his own apartment near his family, and a romantic relationship one day.

“You know, he wanted to have a girlfriend,” his father said. “He wanted a normal life.”

New Hampshire Bulletin is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. New Hampshire Bulletin maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Dana Wormald for questions: info@newhampshirebulletin.com.