When we’ve been exposed to something that could harm us, what are we supposed to do — as regulators, as doctors, as company executives, or as people just trying to live our lives?

Explore a timeline of the PFOA contamination in Merrimack, New Hampshire:

Documents & Resources

We reviewed hundreds of documents for this project. We’ve included a few below.

- Merrimack community health survey: This is the analysis of Laurene Allen’s community health survey done by scientists at the University of Vermont.

- Merrimack kidney cancer study: This is the kidney cancer study conducted by a Dartmouth University team in collaboration with the State of New Hampshire.

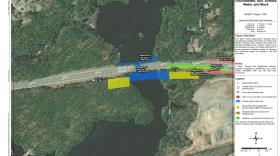

- Saint-Gobain’s legal agreements: These are the consent decrees that Saint-Gobain and the State of New Hampshire agreed to in 2018 and 2021. A map of “the ring,” or the boundary for water remediation, can be found here.

- The EPA’s regulations on PFOA and other PFAS: This is a description of the EPA’s maximum contaminant limits for PFOA and a few other PFAS chemicals.

- Saint-Gobain’s remediation plans: Saint-Gobain submitted a remedial action plan in 2023 and an update in early 2024. In October 2024, state regulators said the plans were “inadequate as they present no proposed effort to reduce high concentrations of contamination” and asked the company to revise the plan. Saint-Gobain is now collecting more data at the site.

So, you want to figure out if YOUR water has PFAS in it. Here’s how:

PFAS chemicals have no taste, smell, or color. The only way to tell if they are present is through water testing. A 2023 study from the U.S. Geological Survey found that at least 45% of U.S. drinking water samples contained PFAS.

Public water systems across the country are required to start monitoring for PFAS chemicals that have been regulated by the EPA. Under the Biden administration, the EPA initially moved to regulate PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA (aka GenX), and PFBS. However, the Trump administration announced in May 2025 that the agency intends to rescind and reconsider regulations for these chemicals, except for PFOA and PFOS.

The administration has also proposed extending the deadline for water systems to comply with regulations to 2031. Originally, water systems would have been required to provide public information about the levels of those chemicals by 2027, and to implement solutions for high levels by 2029.

Your water system may have already tested, and you can contact them directly to find out.

This dashboard is where New Hampshire residents can find PFAS testing results in their area. This dashboard from the nonprofit Environmental Working Group and this dashboard from the U.S. Geological Survey show national PFAS testing results. This database contains results from public water systems that tested for PFAS during the EPA’s Fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule.

If you have a private well or you get water from a spring, you may need to test for PFAS chemicals on your own. Many states have guidance to help with testing.

This resource from PennState Extension explains the numbers and acronyms found in PFAS testing results. So, if you get your water tested, this guide can help you understand the lab reports.

This tool from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention can help you estimate the levels of certain PFAS chemicals in your blood based on the levels in your water.

Editor's note: This section has been updated to reflect potential new regulatory changes under the Trump administration.

Transcript

Mara Hoplamazian, narrating: Reporting on contaminants has caused me to ask some strange questions over the past few years… like how does a mass spectrometer work? And what are the ethical considerations for using zebrafish as test subjects?

Or if someone, say a friend of mine, were to use their favorite rice cooker four times a week for about 20 years, how much of the nonstick coating might leach into their rice?

Here’s another thing I started wondering recently. If a PFOA molecule was sentient, what would it see? What would it feel?

First, the inside of a lab, bright fluorescent lights.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Next, maybe, a vat. Then, the sensation of moving, the whoosh of a highway.

A man in a uniform, carefully transferring liquid into a trough. A woven sheet of fabric. The burn of a 750-degree oven.

Suddenly, through a cloud of smoke, green trees. Gentle wind over a New England town.

Grass. Dirt. The soak of a heavy rain. Groundwater.

Then, some pipes. A faucet. The edges of a Brita filter. A glass with a lemon wedge. A glimpse of a sunny day. Teeth and a tongue. Esophagus, stomach, small intestine, kidney.

[MUSIC OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: I talked to Megan Romano, an epidemiologist at Dartmouth, about what happens next, about how these chemicals go from an environmental problem to a human health problem.

Megan says, generally, our bodies have systems to kick out toxic stuff.

Megan Romano: It's almost like putting a luggage tag on your suitcase at the airport and saying, "Okay, this, this one's going out. Kindly discard of this parcel."

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Then we poop or pee or sweat and those toxins are gone.

Sometimes the luggage system doesn't work so well. Chemicals like DDT and PCBs can get stuck in the fat in our organs. But forever chemicals are different. Megan calls them "chemical weirdos."

They have unique properties, which is part of why they’ve been so useful for making so many things… and also why they can be so bad for us.

Romano: And we think this is part of why PFAS seem to affect so many different aspects of health is because they are able to kind of hang out in the blood. And that allows them to reach many, many target organs and affect many different places in the body, as opposed to really congregating in, in one section or another.

Hoplamazian, narrating: In other words, PFAS molecules don’t get luggage tags, but they do stick to proteins in our blood. And over time, they can really build up.

Remember, in water, scientists measure PFAS in parts per trillion. But in blood, they use a unit of measurement that’s a thousand times bigger… parts per billion.

[MUSIC OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: The average American nowadays has about one and a half parts per billion of PFOA in our blood – that’s 1,500 parts per trillion.

And in the years since the C8 study, the more scientists research what these chemicals do as they accumulate in our bodies, the more havoc they seem to uncover.

There’s evidence that PFAS chemicals could disrupt the signals our bodies send through hormones. They could change the way our genes express themselves. They could suppress our immune systems. They could get into a cell and create particles that bounce around and cause chaos.

In other words, it looks like PFAS can interfere with our cellular biology. That interference can lead to rogue cell division, uncontrolled growth – cancer.

But to say that one thing can cause another – like, exposure to PFOA can cause kidney cancer – doctors usually want to see a randomized clinical trial. Megan says that’s the gold standard of evidence.

The problem is, it would be wildly unethical to randomly expose people to toxins.

Romano: Sometimes we find ourselves at a disadvantage where we have to use observational studies. We have to look at people who were exposed and understand what's going on and that we observe. We, we look and follow them and see what's happening.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Over time, if different people are exposed to the same things and experience the same symptoms, scientists start to believe it could be causal.

But unlike clinical trials, observations are messy. Sometimes studies find something in one population, but not another.

Scientists can now say with confidence that PFOA is carcinogenic. Studies have connected it to testicular cancer and kidney cancer. But for something like breast cancer, Megan says the evidence isn’t as straightforward.

For Megan, that kind of uncertainty is okay. It’s kind of her whole world.

Romano: Like, as an epidemiologist, I love to say, "This is associated with that." And I know exactly what I mean. That is a very precise, technical meaning to me. And those words mean that I am neither over- nor under-interpreting my, uh, findings.

[THEME MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: This brings us to another strange question I’ve come across while reporting on PFOA contamination.

It was posed during one of the many public meetings I’ve watched on YouTube – by a guy who used to work for a branch of New York State’s health department.

He said imagine someone is offering you a plate of cookies. Does it matter to you if they say, "Those cookies cause cancer, those cookies are associated with cancer, or there’s a link between those cookies and cancer?"

He asked, "In any of those situations, do you wanna eat the cookies?"

[THEME MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: This question about the cookies… it's really the heart of this whole story.

Humans are notoriously bad at understanding health risks.

So, when you’ve been exposed to something that could harm you and you can’t find a clear answer about what might happen next, what do you do? How do you move forward?

Wendy Thomas: Yeah, we won, but the door prize was, ya know, illness.

Jen Peirce: That is my biggest worry that they or even us, will be affected 10, 15 years down the road. And… what is justice for that? I-I don't know.

Hoplamazian, narrating: From the Document team at New Hampshire Public Radio, I’m Mara Hoplamazian. And this is the final episode of Safe to Drink.

[THEME MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: For a long time, it was hard to get your blood tested for PFAS, to get proof this stuff was actually building up in your body.

Blood tests were easier to come by if you lived in a place with known contamination like Hoosick Falls.

New York State’s health department started offering blood tests there in 2016. One person who took them up on it was Loreen Hackett.

Loreen Hackett: We got the blood test results back and my family's levels were… extraordinary.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Remember how the average level of PFOA in human blood these days is about one and a half parts per billion? Loreen’s blood and her family’s blood were testing in the hundreds of parts per billion.

Hackett: I'm not an activist, but I was pissed off. So I'm a pissivist, [LAUGHS] ya know? Everything just pissed me off. I was pissed, I was beyond angry, knowing that now this was done to us.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Like pretty much everyone else I talked to, Loreen hadn’t heard of PFAS chemicals before she found out they were in her water – and blood. She started reading health studies, the same ones Michael Hickey and Laurene Allen read. In fact, Laurene Allen got some of her research directly from Loreen Hackett.

“The Laurenes” – they have kind of a reputation among PFAS activists. Especially Hackett. A couple people told me, "You don’t mess with Loreen Hackett."

When we met up, I got what they were saying. She’s got a good hard stare, the kind that makes you squirm a little. She told me she was healing from a hip replacement. By her count, her sixteenth surgery.

Loreen has had a tough medical journey. After she had her second daughter, she had a hysterectomy. She got diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis in her 20s and a few other related conditions. She had breast cancer.

Hackett: [LAUGHS] I could be the walking billboard of this can go wrong and this can go wrong and this can go wrong. And sadly, so are my children and my grandchildren.

Hoplamazian, narrating: After she got her family’s blood test results, Laureen started a Twitter account. She took a photo of her grandson holding up a sign with his blood levels on it. She took one of her granddaughter, too. She posted them in black and white.

Hackett: And all I could think of was, "Well, if you won't hear us, all our yellin', you're gonna see us."

Hoplamazian, narrating: Suddenly, the photos were everywhere. Other people in Hoosick Falls started posting similar ones with the number of PFOA parts per billion in their blood. The images made it into newspapers. Loreen started hearing from people across the world.

With her grandson as a profile photo, Loreen posted news articles and health studies. Her Twitter profile became kind of like an unofficial library on forever chemicals.

Hackett: When there's no answers, you, just like, "Okay, I got just dealt a really bad hand, you know?" And then to start finding out through health studies and all that research that, oh, well, this has an effect and this has an effect. And PFOA is linked to these, these, these, and light bulbs start goin' off. Um, and so I just kept diggin'.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Remember, the C8 study found “probable links” to six illnesses – kidney cancer, testicular cancer, thyroid disease, ulcerative colitis, high cholesterol, and pregnancy-induced hypertension.

You might also remember that study was part of a major lawsuit settlement and was paid for by DuPont itself. The phrase “probable links” has meanings that are both scientific and legal. People in the Ohio River Valley with some of those conditions sued DuPont and won.

Scientists have studied PFOA’s connection to lots of other health outcomes, including some of Loreen Hackett’s diagnoses. But there’s nothing like the C8 study that legally defines how much proof would be enough to hold up in court. So, Loreen says she’s still waiting for the day a lawyer decides to take up a case like hers.

Hackett: How many studies does it take? I ask the question all the time. I can't get an answer. How many studies does it take to prove a chemical… is linked to a health condition?

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: The Laurenes say proving these links is about more than finding an explanation for suffering – it’s also about holding polluters accountable.

Laurene Allen: People don't accept responsibility when they do harm unless you can prove it and make them. And how do we do that? We have only one venue. We can raise our voices. We can say all the right things. Everybody can listen and say, "Oh, my God, that's terrible!" But that doesn't do a damn thing. It's the legal system that actually delivers that.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Over in Merrimack, New Hampshire, Laurene Allen began pushing state officials to do a health study. Her hope was that they could start saying with more certainty what Saint-Gobain’s contamination had done to her community’s health. But she says her pushing wasn’t very well received.

Allen: And then, I said, "Alright, I'm gonna have to do this on my own."

Hoplamazian, narrating: Remember, Laurene is not a scientist. And she knew she probably wasn’t going to be able to prove, once and for all, that PFOA caused particular health effects.

Still, with help from a nonprofit and other people in the community, she designed a survey. It was low-key – a link to an online form on fliers at the library and the town hall. Laurene also organized a team that went door-to-door in their neighborhoods.

Laurene says sometimes when she was door knocking, people asked her the same questions state officials were getting. "Am I sick because of the water?" Some of the door-knockers gave the answer a scientist might. "We can’t really say." But Laurene took a different approach.

[MUSIC OUT]

Allen: I'd be like, "Don't say that. You don't have to say, 'Yes, that's it.' But don't say. We can't really say. Just listen." People know what they know. And if they say, "I know this and this is my truth," ya know, who am I to say otherwise?

Hoplamazian, narrating: Almost 600 people took the survey. That’s only about 2% of Merrimack’s population, but for Laurene, it was a big deal.

Even with the survey’s obvious limitations, researchers at the University of Vermont analyzed the results and they noted some red flags that begged more research like higher numbers of reproductive, autoimmune and kidney disorders among kids and more health concerns among the people who lived in Merrimack longer.

Eventually, the state of New Hampshire did start its own health study. And in one way, it seemed to vindicate Laurene and the other activists.

The study found evidence that the rate of kidney cancer in Merrimack is higher than in the rest of New Hampshire. 38% higher.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: But the study couldn’t say exactly why. The authors, including Dartmouth epidemiologist Megan Romano, said they’d need to do another, even bigger study to determine that.

So, more potential evidence, but no solid proof.

Wendy Thomas: Can we prove this? I don't know, ya know, but… again, if it looks like a duck, if it quacks like a duck, ya know, if it swims like a duck, I think we're looking at a duck here.

[MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: After Wendy Thomas found PFOA in her water, it suddenly seemed like there might be an explanation for the health problems she and her family were having…

[MUSIC OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: …Issues with their joints, cholesterol, and kidneys. Wendy survived breast cancer. There are three small dogs buried in their backyard and a fourth cremated. They all died of cancer.

And it’s not just her family. Wendy says she sees it all over her neighborhood.

Thomas: The house across the street, which has a private well, which is also contaminated, the dad in that house died of kidney cancer. Um, further up the street, they have a private well that's contaminated. The son died of colon cancer. The father died. He had colon cancer, but it was really his bladder cancer that eventually killed him. And then, our neighbor next door, the dad currently has prostate cancer that has metastasized to his bones. Um, he seems to be doing pretty well, but, ya know, um, that's… that's a lot of quacking in just one street.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: I’ve heard this kind of thing from a lot of people in Merrimack. When it seems like everyone around you is sick, it’s hard not to see every illness as a dot to connect.

There’s this idea that’s getting more traction in the United States – call it TikTok wellness culture, or the Make America Healthy Again movement, or the more radical parts of “crunchy mom” reddit. The idea is that the whole world is full of toxins and we can’t trust government agencies or academic institutions to keep us safe.

While working on this story, I've found so many echoes of this feeling.

Of course, unlike forever chemicals, there is a lot of science backing up the safety of things public health officials tell us to put in our bodies on purpose like fluoride and vaccines.

But to hear your water has been contaminated by a huge corporation, to get confusing information about whether that water is safe to drink, to see people getting sick all around you, and then to be told, we don’t know if those two things are connected… it’s no wonder so many people feel like they need to do their own research – protect themselves.

And in many ways, that’s exactly what people in Merrimack did.

[MUSIC OUT]

Thomas: You know, a lot of people ask me, "Why haven't you left? Why haven't you gone someplace safer?" And it's like, if I leave, who is going to be staying here to fight and do the work that's necessary to, to keep this town safe?

Hoplamazian, narrating: Pretty soon after Merrimack found out their water was contaminated, Wendy got to work. She connected with a group of women in town.

In 2018, three of them decided to run for state office. A reporter called them "the Water Warriors." The name stuck. And… they won.

Thomas: I mean, we were evangelical about PFAS when we got up to the State House. Ya know, I would introduce myself. I'd say, "Hey! I'm Wendy Thomas, I'm from Merrimack. Do ya know about PFAS?" [LAUGHS] And I would just, I mean, they're like, "I don't know about PFAS, but let me eat my, my lunch and we can talk about it." And I'll be like, "Yeah, yeah! Eat your lunch and let's, let's talk."

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Wendy was joining the ranks of PFAS advocates across the country.

The Laurenes helped start a group called the National PFAS Contamination Coalition. The casts of all the local productions of this play were starting to organize from New York and New Hampshire to North Carolina and Washington State. PFAS started to become more of a household name. The need to do something was becoming harder to ignore.

So, state governments started doing something.

In New Hampshire, one of the main things state lawmakers did was to tell regulators to create statewide limits for PFOA and a small group of other PFAS chemicals in drinking water.

Remember, New Hampshire got sued for setting those limits. But eventually, they were adopted and the state became one of a handful with legal, enforceable limits for PFAS in drinking water.

When New Hampshire adopted those in 2019, they were some of the lowest in the country, 12 parts per trillion for PFOA.

It took the feds another five years. But in 2024, the EPA finally announced their drinking water standard for a few PFAS chemicals – the thing Rob Bilott, the lawyer from the West Virginia case, had been asking them to do for more than a decade.

For PFOA, the federal limit is now four parts per trillion. Four.

But federal regulators say if the level was set solely based on health, not taking cost or feasibility into consideration, the limit would be zero.

In other words, there is no level of PFOA in water that is safe to drink.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: In many ways, Wendy says, the Water Warriors won their battle. Their research and their advocacy made a difference. But it’s hard to say how much of a difference.

Thomas: It's a bittersweet, uh, win, you know, because, uh, all of us, all three of us are sick. We've all got health issues. Our families are suffering. Um, so, yeah, we won, but, but… the door prize was, ya know, illness.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: The Water Warriors and other PFAS advocates helped prevent future New Hampshire residents from being exposed at high levels.

But what about all the people who had already been exposed? And what about the miles of soil and water around Merrimack still contaminated with a colorless, odorless chemical? That’s next, after the break.

[MUSIC, CREEPY TONE UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: By the way, if you want to know whether your drinking water has forever chemicals in it, we’ve put together some resources for you. Find those on the "episode 4" page of our website, NHPR.org/SafeToDrink.

[MUSIC, CREEPY TONE OUT]

[MUSIC IN]

Jason Moon, narrating: I’m Jason Moon. I’m one of the producers of this series.

You probably know that documentary podcasts like Safe to Drink take a huge amount of work. Mara didn’t just hop into a studio one day and talk into a microphone.

Mara has been reporting on PFAS contamination in New Hampshire for years. And then, we spent another whole year working just on Safe to Drink. We collected and read thousands of pages of documents. We gathered more than 80 hours of raw audio, from interviews with more than 30 people, traveling hundreds of miles in the process.

And then, to make sure we got the story right, we hired an independent fact-checker to confirm every detail. In the script that I’m looking at right now, there’s a footnote after almost every single sentence that lists the sourcing.

Point is, making this kind of podcast is expensive. It would’ve been a lot cheaper if Mara had just hopped into a studio one day. But we think it’s worth it to make a series that’s rigorously reported, that's accurate, and that you’ll actually want to listen to.

And here’s the truth. We can’t do this work without your support – especially now.

Federal cuts to NHPR, the station that produces this podcast, have reduced our funding by hundreds of thousands of dollars. You might’ve heard a few ads while listening to this podcast. Let me be real – they do not come close to covering our costs.

Public media is possible because of public support. You can make a gift right now on your phone with Applepay or on the app of your choice. Just hit the link in the show notes. And, seriously, thank you.

[MUSIC OUT]

[MIDROLL BREAK]

Hoplamazian, narrating: As New Hampshire lawmakers were trying to make sure this kind of thing wouldn’t happen again, Saint-Gobain was chugging along, still coating fabrics in their factory by the Merrimack River.

Around 2018, testing showed the plant was emitting much less PFOA than it used to. But 190 different PFAS compounds were still coming out of the stacks. State regulators estimated the plant was releasing more than 850 pounds of forever chemicals per year, a quarter pound every hour.

Saint-Gobain has always insisted that they’re not necessarily responsible for the contamination in Merrimack. But by 2019, the state of New Hampshire had determined Saint-Gobain’s emissions did put PFAS chemicals into drinking water and they were continuing to contribute to the problem.

State regulators said they didn’t have the legal authority to tell Saint-Gobain to shut the plant down altogether. Instead, they were asking the company to install a new device that would limit the pollution, something called a regenerative thermal oxidizer.

It took Saint-Gobain almost a year and a half to install that device, which meant with each passing day, more PFAS chemicals kept going into the air.

Ben Peirce: They were still… running! They were still running, just full operations, still makin' money, still doin' their thing.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: You remember Ben Peirce. He found the cases of bottled water in his driveway.

When New Hampshire first started investigating the PFOA contamination, they did a lot of testing. Air, soil, public water. They also tested private wells.

It was a big undertaking, so they started with wells closest to Saint-Gobain. Then, they began testing wells further and further out until they reached the town of Londonderry where the Peirces live.

Eventually, Ben and Jen Peirce pieced together that one of the first wells the state tested in their neighborhood was their own. It was tested about a month before they moved into their house in 2019.

Now, they were getting bottled water from Saint-Gobain. But only a handful of other homes in Londonderry got tested around the same time the Peirces did. And they realized a lot of their neighbors, they might not know that their water could be contaminated. They started to feel strangely lucky.

Ben Peirce: At the very least, it was months that we weren't just drinking the water, which our neighbors were, ya know?

Hoplamazian, narrating: At the time, Ben and Jen weren’t getting much information from the state or from Saint-Gobain. They decided if they wanted their community to know what was happening, they’d have to take things into their own hands.

So, in the fall of 2019, about a month after their first bottled water delivery, they wrote a letter.

Ben Peirce, reading: "Hi, neighbor. We live at [ADDRESS BEEPED] and our well water tested high for PFAS, a chemical pollutant found in air and groundwater. This means our water is not safe to drink, cook with, or brush our teeth. It is supposedly safe to wash dishes, clothes, etc. The Merrimack company responsible for this pollution and contamination, Saint-Gobain, is providing us with bottled water…" [FADES OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: The Peirces also gave their neighbors detailed advice on how to file a request for the state to test their wells, advice that was hard to find anywhere else.

Ben Peirce: "Click on 'getting your well water tested' in the drop-down menu. Click on 'private well testing request form' on the side menu. Good luck and be safe, The Peirces."

Mara Hoplamazian, off mic: Wow…

Jen Peirce: You can tell I'm a teacher [BEN LAUGHS] 'cause I had to put all the directions. But it was, it was tough to find and I sought it out, so I wanted to be very clear. I wanted people to not be shy about… [FADES OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: They drove around the neighborhood and stopped at every home to drop the letter off. Jen says it just felt like the neighborly thing to do.

Jen Peirce: We did hear back from a few neighbors about, "Hey, we–! We're getting bottled water now. Thank you for giving us that letter. We didn't know about it…" [FADES OUT]

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: As the state was testing all these wells, they were also negotiating with Saint-Gobain about what to do for people whose wells were contaminated. Eventually, they struck a deal.

They drew a big ring on a map with Saint-Gobain’s Merrimack plant in the middle. The company agreed to deliver safe drinking water only to the people with contaminated wells inside that ring, which covers about 65 square miles. As of now, state officials have tested about 4,000 wells inside that ring.

When New Hampshire adopts the legal federal limit for PFOA – four parts per trillion – about three-quarters of those wells within the ring will be over the limit.

But the state has also been testing wells outside of the ring. And officials say it’s clear that there’s contaminated water far beyond this legal border.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: The boundary of that ring goes right through the Peirces’ neighborhood.

Ben Peirce: You can see it from here. [DOOR CLOSES] It's like High Range Road is the boundary. [PLASTIC RUSTLING SOUND] And people right on the other side of that street don't get it for free and they have the same problem.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Ben says he doesn’t talk to their neighbors about the water very much.

Ben Peirce: I think people are private about it. I think, like, even though we're all dealing with the same thing – most of us, again, like, it's not everybody. But I think there's still, like, you know… Because when you talk to your, your family about it and your friends about it, like, there is a little bit of, like, your house is broken, you know, like… I don't know. It's, like, slightly embarrassing.

Hoplamazian, narrating: It’s hard to know when this will all be fixed or even what “fixed” would look like.

For homes with contaminated wells, Saint-Gobain has agreed to pay for home filtration systems or connections to nearby public water systems. But Ben and Jen and other people in Londonderry are still waiting to see when that might happen.

Jen Peirce: We're just stuck in this area that's in limbo right now, so we're just waiting and… waiting and waiting.

Hoplamazian, narrating: There’s another thing making the Peirces feel even more uncertain about where this is all going. In the summer of 2023, Saint-Gobain announced it would be shutting down the Merrimack plant.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: The company said it was part of a restructuring. More than 160 workers were either transferred to one of dozens of the company’s other manufacturing plants or laid off.

Saint-Gobain demolished their factory. Where the plant used to stand, there’s now a bare concrete slab, some trees and soil, a brook that flows into the Merrimack River.

The groundwater on the site is testing about 1,000 times higher than New Hampshire’s drinking water limit for PFOA. There are also high levels of PFOA in the soil.

Saint-Gobain has submitted some plans for remediating the site. But according to state regulators, it’s a stretch to call what they’re proposing “remediation.”

They want to do something called natural attenuation. It’s a fancy way of saying, don’t do anything and let the PFAS disappear on its own – a tough sell for a so-called forever chemical.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: So, Saint-Gobain is gone from Merrimack. But there are other big questions that aren’t going anywhere, like who’s paying for all the different parts of this cleanup project?

The company is required to find permanent solutions, like connections to public water systems, for more than 1,800 homes with private wells. In the meantime, they say they’ve distributed nearly 500,000 gallons of bottled water.

Meanwhile, Merrimack taxpayers spent $14.5 million on a new filtration system for their public water. Saint-Gobain agreed to contribute more than $3 million to that project. But the town will have to keep paying to take care of the filters after they fill up with PFAS.

Merrimack’s water system is suing Saint-Gobain and other companies that used PFAS to try to recoup some of the costs.

And over a thousand people who drank the water, and who think it made them and their family sick or worry they could get sick in the future – they have a case that’s been snaking its way through New Hampshire courts for years.

One thing people really wanted the company to pay for is called medical monitoring. Basically, extra-careful checkups with doctors for a long time to try and catch any illness early.

In other states, like New York, Saint-Gobain has been forced to help pay for 10 years of medical monitoring. In New Hampshire, the issue went to the state supreme court.

[MUSIC IN]

Lawyers for Saint-Gobain argued exposure to PFOA is different from, say, a car crash. If you get injured because someone rear-ended you, you might sue them over that injury.

But with PFAS exposure, Saint-Gobain argued, there's no way to know if a person is injured. There’s just the possibility of an injury at some point down the road.

They also said medical monitoring wouldn’t be feasible because too many people have been exposed to PFAS or at least, it would be really, really expensive. The Saint-Gobain lawyer told the judge, "You and I have never met a person in southern New Hampshire who wouldn’t be part of this class."

[MUSIC, CREEPY TONE UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: In the end, New Hampshire’s supreme court justices sided with Saint-Gobain. So, in New Hampshire, no matter what a jury decides in their class action case, people will be on their own when it comes to tracking their health.

[MUSIC, CREEPY TONE OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: The Peirces only drank their contaminated water for a few months. The chemicals can get into our bodies through our skin, but all the official guidance says the stuff the Peirces are still using their water for – showering, washing dishes, filling up their backyard pool – that should be okay.

Still, Jen says sometimes she’ll have a night of worry about her kids, just full of fear for their future. I tried to ask Jen… how do you live with this?

Jen Peirce: You have to just move forward and not think about those things all the time, but that is my biggest worry that they – or even us, will be affected ten, 15 years down the road and… what is justice for that? I-I don't know.

Ben Peirce, off mic: Yeah…

Jen Peirce: There is no justice for that, I think, if that were to happen. But, but right now, you know, that it hasn't happened. So, it's hard to live in that space, I guess.

Ben Peirce: Yeah… I think we're realistic about the fact that it's really at the end of the day, it's an inconvenience for us at this point. Um, what we're probably not realistic about is that it is way more than an inconvenience, that it is a legitimate health risk for our children, and, um… At some point, there, like, yeah, maybe we'll feel different about the idea of justice... Um, yeah…

Hoplamazian, narrating: While we were talking, Ben and Jen and I were standing in their kitchen. Parker and Kinsey were drifting in and out of the room, going off to play when they got bored of my questions. But when their parents started talking about cancer, they both hovered a little closer.

Ben Peirce: Do you guys think about the scariness of our water? Like, a-are you…

Parker Peirce, off mic: No, I didn't even– I didn't know I could get cancer!

Ben Peirce: Yeah, that's that's the worry. I mean, that's why it's not safe to drink.

Hoplamazian, narrating: We kept chatting. I think I was feeling uncomfortable. I wanted to reassure the kids that their family was following the rules, taking all the precautions. They weren’t exposed for nearly as long or at nearly as high levels as other people I’ve talked to.

Parker seemed like he was getting nervous. He was smiling and laughing. But I was an anxious kid. I could tell something was up.

Parker Peirce, laughing: I have to admit. I think, like a couple of weeks ago, it was in the morning… and I was really tired… and I woke up… and I got dressed, and then, I went to brush my teeth and I used the tap water…

Ben Peirce: Did you really?

Parker Peirce: Yeah, just once. Because the, the– I was upstairs and the thing upstairs wasn't filled and I didn't, and I had nothing up there, and I didn't want to walk all the way downstairs…

Ben Peirce: Oh, so it was like a conscious, like, "I'm gonna, I'm gonna live on the edge, ride the lightning!" [LAUGHS]

Parker Peirce: And I was like, "It's probably fine." And then, so I just…

Ben Peirce: I think one tooth brushing is probably okay.

Parker Peirce: …I just wet my toothbrush with it.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Risk management isn’t the hardest part, Ben told me. It’s the emotional management. It’s trying to find the right amount of fear to have when there’s a toxin all around you and all you can do is wait to find out whether something bad is going to happen.

[THEME MUSIC UP AND OUT, CREDITS MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Safe to Drink is reported by me, Mara Hoplamazian.

Additional reporting and production by Jason Moon, who also mixed all of the episodes, drove us all around Vermont and New York, and created all of the music you hear in this podcast.

Our editors are Daniela Allee and Katie Colaneri.

Editing help from Daniel Barrick, Rebecca Lavoie, Taylor Quimby, Elena Eberwein, and Lau Guzmán.

A very special thanks to everyone whose work and support made this project possible including Lauren Chooljian, Casey McDermott, Kate Dario, Julia Furukawa, Zoey Knox, James Freeman, and my siblings Lena and Leo.

And a huge shoutout to all of the excellent journalists whose work I relied on while reporting this story, many of them local reporters just like us at NHPR, including Annie Ropeik, Mariah Blake, Sharon Lerner, Nathaniel Rich, Howard Weiss-Tisman, and Brendan J. Lyons.

Fact-checking by Dania Suleman.

Legal review by Jeremy Eggleton.

Photos by Raquel Zaldívar with the New England News Collaborative.

Sara Plourde designed our website, NHPR.org/SafeToDrink, where you can check out the Merrimack community health survey, maps of New Hampshire’s PFAS sampling efforts, the lawsuits we talked about, and a bunch of other photos and documents.

Nate Hegyi designed our logo.

Dan Barrick is NHPR's News Director, Rebecca Lavoie is our Director of On Demand Audio, and Leah Todd Lin is Vice President of Audience Strategy.

Safe to Drink is a production of the Document team at New Hampshire Public Radio.

[CREDITS MUSIC UP AND OUT]