We go back in time to Hoosick Falls, New York where a man looks for answers after his father dies of cancer following his retirement from the local Saint-Gobain plant. What he finds changes the course of this whole story: a remarkable kind of chemical once used to help make the Atom Bomb that manufacturers knew could be dangerous for decades.

Explore a timeline of when information about PFOA became public:

Documents & Resources

Below is camcorder footage West Virginia farmer Wilbur Tennant recorded in the mid-1990s. Tennant, whose farm was adjacent to a DuPont landfill, made these videos to show the impact he suspected contaminated water was having on his cows and other wildlife — so, a heads up, this video contains graphic scenes of dead animals. Tennant's lawyer, Robert Bilott sent this footage to the U.S. EPA in 2001. Their landmark case was featured in the 2019 film "Dark Waters," starring Mark Ruffalo as Bilott.

We also reviewed hundreds of documents for this project. We’ve included a few below.

- Robert Bilott’s letter to the EPA

This is attorney Robert Bilott’s letter to the EPA, sent March 6, 2001, which outlines what DuPont and 3M knew about the potential health risks of PFOA as far back as the early 1960s.

- DuPont and 3M studies on PFAS chemicals

This is a list of studies conducted by DuPont and 3M on PFOA from 1961 to 2002. This is a 1970 document describes “polymer fume fever.” This is a document from 1975 that describes PFOA (APFO) testing on rats and dogs. This is a 1981 memo describing DuPont’s warnings that PFOA had been found to cause birth defects in unborn rats, and that the company had reassigned female personnel away from areas that used the chemical.

- Judith Enck’s letter to Hoosick Falls

This is the letter then-EPA Administrator Judith Enck wrote to then-Hoosick Falls Mayor David Borge on Nov. 25, 2015, recommending the town stop using the water for drinking and cooking.

- C8 Science Panel

This is the website for the C8 Science Panel where you can find all the peer-reviewed studies finding probable links between PFOA exposure and six illnesses.

- “They Poisoned the World” by Mariah Blake

Mariah Blake’s book follows the story of PFAS chemicals in Hoosick Falls and throughout their history in the United States. Blake also wrote an article on the Tennant family’s case against DuPont in West Virginia.

- “The Teflon Toxin” by Sharon Lerner

Sharon Lerner wrote a series of articles for The Intercept in 2015 about DuPont’s Parkersburg, West Virginia plant and the history of Teflon.

- "Exposure" by Robert Bilott

Robert Bilott's memoir details his experience of taking on Wilbur Tennant's landmark case against DuPont in West Virginia.

- Information on PFAS chemicals

This is the EPA’s website explaining PFAS chemicals.

Transcript

Mara Hoplamazian, narrating: Loreen Hackett also thinks it’s funny that she shares a name with Laurene Allen. They run in the same circles now. I’ve heard them called “the Laurenes.”

Loreen Hackett: In our group, we use our last names. “Yo, Hackett!” [LAUGHS] Loreen 1, Laurene 2 doesn't work ‘cause we never know which one's which!

Hoplamazian, narrating: The Laurenes met because the same thing happened to their water. In their two small towns, about 100 miles away from each other, they were both drinking the same chemical.

They also met because… well, they’re kind of birds of a feather.

Laurene Allen: I was in lock-on-target mode. That part of me that really is about justice just was like, RAH!

Hackett: I'm not an activist, but I was pissed off. So, I'm a pissivist. [LAUGHS] Ya know? [FADES OUT]

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: I promise we’re gonna spend more time with the Laurenes. But first, I need to tell you the story of how Loreen Hackett found out there was something up with the water in her town… Hoosick Falls, New York.

Because… if not for what happened in Hoosick Falls…people in Merrimack, New Hampshire might still not know about the chemical in their water.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: It started with a guy named Michael Hickey.

Michael was never one to speak up. He says he’s a behind-the-scenes kind of guy, like the kid in the back of the class.

Michael Hickey: I'm a little bit timid, right? I don't, I don't like public speaking. My voice is shaky on doing this podcast, right?

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Michael grew up in the town of Hoosick Falls. It’s a beautiful spot in upstate New York, built along two rivers. There’s a folk artist, Grandma Moses, who got popular in the 1950s partly for her scenes of the area – covered bridges, little white houses with big chimneys, rolling hills under blankets of snow.

Michael really liked his childhood there. He got along well with his parents. They both had jobs at a local factory owned by Saint-Gobain.

Hickey: It's a blue collar lifestyle, right? And, and they were lucky and we were lucky as, as their kids being my brother and my sister to be brought up that way.

Hoplamazian, narrating: His dad worked the overnight shift. 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. And then he would leave work and go drive a school bus.

Hickey: He drove from 7 to 8:30. He went home. He slept from 8:30 to noon, and he drove from noon to 5 and he did it all over again… for 32 years. And then, he drove limos on the weekends.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Everyone called Michael’s dad Ersel after a rockabilly singer named Ersel Hickey.

Ersel was beloved. He wore bright shirts and polka-dot shorts. He served in local government. Michael says he never heard him say a bad thing about anyone. And he never saw Ersel smoke or drink. He took his work seriously.

Hickey: Once he got the job driving the school bus, he never wanted there to be a question, um, if he was hungover on a Monday morning or if he had any kid in his control that– he didn't want to ever be a question if he was that guy out drinking at the bars. Small community, people talk, and he never wanted that.

Hoplamazian, narrating: When the time came to retire, Ersel was excited to travel. He’d worked hard, saved up. He had an RV. He left his job at the Saint-Gobain factory first. Then, he stopped driving the school bus.

And then, seven months later, he died. He was 70.

Hickey: I-It was awful. Um, he didn't… He fought until the very end. Like, a lot of people say, uh, “They're in a better place.” And he didn't want to go anywhere.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Ersel died of kidney cancer in the winter of 2013. At first, his family had thought he'd be able to beat it. Then it spread.

Michael struggled a lot with his dad’s death. He figured Ersel was healthy, didn’t do the stuff people say gives you cancer. He worried about the way he handled his dad’s treatment.

About a year after Ersel died, Michael was sitting at home one night, up late, thinking. A local math teacher he knew had also just died of cancer. She was 48.

Then, Michael remembered hearing about other illnesses around town. A nagging thought entered his mind. Maybe it wasn’t a coincidence that people were getting sick in Hoosick Falls.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Maybe there was a pattern.

Hickey: Then, I started thinkin', “Why are all these people always sick?” You know

“What–?” 'Cause in a smaller community like this, you know what the neighbor has for illnesses. You know what the person down the road has. You know, like… And it seemed like we had a lot of these illnesses. And I'm like, “Wow, what could– What ties everybody together? Water, right? Water does.”

[MUSIC UP]

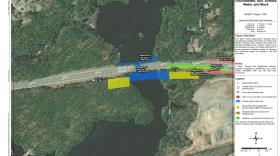

Hoplamazian, narrating: The house Michael grew up in was across the street from the Saint-Gobain plant, about 150 yards away. And the wells that supplied Hoosick Falls' public drinking water were near his house too, about 500 yards away from the plant.

Michael knew what Saint Gobain made – fabrics coated in Teflon. He’d actually worked there too, during his college summer breaks. He scraped the soot out of the exhaust towers.

So, he started Googling. Typed in the words “Teflon” and “kidney cancer.”

[MUSIC OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: He found a group of scientific studies, something called the C8 Science Panel.

It was completed in 2013, less than a year after Ersel died of kidney cancer. Michael saw that the panel listed a bunch of illnesses linked to a chemical used to make Teflon. A chemical called PFOA.

[THEME MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: The study focused on people exposed to the chemical through their drinking water.

Hickey: And I was like, “Holy shit!” The first one that popped up was kidney cancer. That’s what my dad had. And then, I read through it. And then, I was… obsessed.

[THEME MUSIC UP]

Hickey: I couldn't sleep at night, right? Because of stuff with him. And that's what I did. I read so I didn't have to sleep.

[THEME MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Michael found himself in the middle of something that didn’t feel right. But rather than just sit with that feeling, he decided to do something about it.

From the Document team at New Hampshire Public Radio, I’m Mara Hoplamazian. This is Safe to Drink.

[THEME MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: So… Michael Hickey is staying up all night reading scientific studies about PFOA – maybe some of the same ones Laurene Allen would eventually read in Merrimack. And just like Laurene, Michael isn’t a scientist. He reads some of the studies four or five times to understand them.

Hickey: I'm an insurance underwriter. You know, I don't have any science background.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Michael becomes convinced – just like the people in the C8 study, his town was drinking contaminated water. But he figures no one would believe him. Imagine how you’d sound trying to convince your town the water was poisonous.

So, Michael goes to his friend who’s a local doctor. The doctor had taken over a medical practice from his dad, so he had records from people in Hoosick Falls going back 50 years.

Michael points out the list of illnesses from that study he’d found – high cholesterol, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, testicular cancer, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and kidney cancer.

Hickey: He's like, “We see a lot of these illnesses. There could be somethin' to it.”

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: "There could be something to it." But they have no proof that PFOA is getting into the water. There’s only one way to be sure. They have to test the town’s drinking water supply.

To do that, they go to someone with power – the mayor of Hoosick Falls.

Hickey: You know, my hope in the beginning was to bring the mayor a folder and leave, you know, and say, “Here you go. Giddy up. You take care of it. I'm done.”

Hoplamazian, narrating: It didn’t happen that way. The mayor says he’ll talk to the county about it. But the county says… there’s no need to do anything.

In 2014, in the United States, pretty much only public water systems with more than 10,000 people had to get tested for PFOA. Hoosick Falls is too small.

It seems ridiculous to Michael – 10,000 people feels like an arbitrary cutoff. And if there is something in his town’s water that’s making people sick – that might have killed his dad – he has to know.

Hickey: I needed to be able to sleep at night, right? Like, that was the whole thing. I was like… I was so obsessed at that point. I'm like, “Alright, did my dad really get cheated?”

Hoplamazian, narrating: So, here’s where Michael does something big. This soft-spoken insurance underwriter with no scientific background decides he’s going to test his town’s water for PFOA... himself.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Michael calls around and manages to find a lab in Canada that will do it for 700 bucks. All they need is for him to send the water samples in a special cooler.

One day, the cooler arrives and Michael gets to work. He takes these little vials, and he collects samples from his mom's house – that’s the water his dad drank. He also collects water from his own house. But that's not enough.

The lab needs four samples of raw water – the water from the town treatment system before it gets filtered. But there’s a problem. The mayor says private citizens aren’t allowed to access raw water.

Hickey: I was like, “What would be the closest to raw that I could get?” And that would be the two that are on the other side of the river, would be the dollar store and the McDonald's.

Hoplamazian, narrating: The Dollar General and the McDonald’s.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Michael knew they used private wells that weren’t filtered through the town’s system. He figured it would be a good proxy for the raw water. But now he has to get his little vials to a sink at the local Dollar General and McDonald’s without being… weird?

So, Michael hatches a plan. At the Dollar General, he will go in, and very casually ask for the big wooden key to the bathroom.

Hickey: Yeah, I felt a little shady. Yeah. Yeah, it was like… “Alright, I'm really just goin’ in there and taking water, though.” You know, like… But I felt like, “I'm doin’ some crazy shit here. I'm, like, really undercover. I'm like, James Bond type shit I'm doin’.”

[MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: For the McDonald’s job, Michael orders a Happy Meal with his toddler, while his then-wife collects the water from the bathroom. No one is the wiser.

Michael packs up the little vials into the special cooler and ships it off to the lab in Canada. And then he waits.

[MUSIC OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: A few weeks go by. Then, finally, the results.

PFOA is in the water. And not just the background levels that you’d find in almost every water supply. There's lots of it. More than 400 parts per trillion at the house his dad lived in.

Turns out, the mayor, who wouldn’t give Michael access to the raw water, did his own tests. They confirmed Michael’s results.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Almost two years after his dad died of kidney cancer, Michael Hickey had just proven that his entire town was drinking a chemical linked to kidney cancer.

[MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: So, here’s where I thought the story would have ended. This is the big moment, right? They found PFOA in the water... like when the meddling kids in “Scooby Doo” take the mask off of their villain at the end of the episode.

Michael thought it was obvious. A chemical in the water, plus evidence the chemical could make people sick, equals… tell everybody to stop drinking the water. That’s what he and his family did.

But it wasn’t that simple.

The mayor of Hoosick Falls turned to the county public health department. And they told the mayor, basically, “Don't worry, it's all good.” They said the village was in compliance with all of the regulations… which was true.

Remember, at the time, PFOA was not a regulated chemical – even though there was science linking it to some cancers, including that big study Michael had found.

There was just that federal guideline on how much PFOA was safe to drink. In 2014, the EPA’s guidance was 400 parts per trillion. But the guideline was just that – a suggestion. There was nothing legally enforceable about it.

So, even though Hoosick Falls had water testing higher than the EPA's guideline, nobody had to do anything.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: And Michael says it was hard to get many people to believe there was even something going on. After all, PFOA has no smell, no taste, no color.

Hickey: Right? If we, if we had a whole bunch of brown water, people would probably say, “Oh, shit!” But, in this case, you didn't.

Hoplamazian, narrating: But then, in 2015, word of the water issue in Hoosick Falls made it to the desk of an EPA regulator named Judith Enck.

Judith ran the regional EPA office at the time. She’s originally from the area. But when she got a call from a county official, asking for money to help pay for water filters, she was surprised.

Judith Enck: You know, I kind of follow local environmental issues and I'd never heard of this! So, I asked the county executive, “What are you talking about?!”

Hoplamazian, narrating: Then, when she looked at the levels of PFOA in the water, she was even more shocked.

Enck: I spoke to the mayor of Hoosick Falls and I said, “You need to tell the public to stop drinking the water because I'm very concerned about these elevated levels.”

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: But the town and even the state, run by then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo, seemed reluctant to make a big deal out of this.

Judith says the New York state health department told her they had been negotiating with Saint-Gobain and they were close to getting the company to offer free bottled water in the local supermarket. She remembers them asking her not to talk publicly about whether the water was safe to drink.

Enck: And, and I kept telling the Cuomo administration, “You've gotta tell the public. And if you don't, I will.” And… they refused.

Hoplamazian, narrating: So, she did. In November 2015, the EPA sent a letter to Hoosick Falls recommending that people stop using the water for drinking and cooking.

We asked the New York state health department about this moment. They didn’t address whether they asked Judith Enck not to tell the public. But they referred us to testimony officials gave in 2016. They said they were communicating with people in Hoosick Falls about the situation through the county and the town and they were caught off-guard by Enck’s letter. They said it was inconsistent with how the EPA was handling similar situations in the rest of the country.

A few days after the letter, Saint-Gobain began paying for a free bottled water program.

Finally, the whole town was beginning to see what Michael Hickey saw. The kid in the back of the class got everyone to pay attention.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: There’s so much more to the Hoosick Falls story.

Some local banks announced they would no longer issue mortgages in Hoosick Falls. The EPA classified Saint-Gobain’s plant as a superfund site. State officials named PFOA a hazardous substance.

Saint-Gobain and other companies settled lawsuits without admitting any fault or responsibility for the contamination. They paid out millions of dollars to people who drank PFOA for years.

The story made the national news. Legislators called hearings and asked how could this have happened?

Michael Hickey became a leading PFOA advocate. In 2019, Michael’s congressman invited him to President Trump’s second state of the union.

Most importantly, Hoosick Falls installed a treatment system, a series of filters that remove PFOA. After treatment, the water is PFOA-free.

Saint-Gobain’s Hoosick Falls plant is still open. Data taken in 2019 showed the plant was no longer releasing PFOA. It was still releasing other PFAS chemicals. Still, Michael says it’s a good thing that they didn’t leave.

Hickey: These people who live in these communities would work these jobs even if they knew they were gonna get sick. I know my parents would have because what else were they gonna do? And it's just really unfortunate that these companies, they knew for a long time what they were doin', right? And they took advantage of these blue collar communities, right? Thinking, “Alright, it's our lifestyle. We're drinkers or smokers. They–” you know, “They don't take care of themselves. That's why they're getting sick,” when in reality, it's the chemicals they're working with.

Hoplamazian, narrating: But besides a few plaques from the EPA, Michael says he doesn’t feel like he has much to show for his work. How do you measure the absence of suffering?

Hickey: Nobody will ever know what we actually accomplished, right? Because people just won't get sick and they won't die, right? So, nobody will really know what we accomplished.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: One of the things Michael and others in Hoosick Falls did accomplish was waking up other towns with Saint-Gobain plants to what was in their water.

As a direct result of the Hoosick Falls story, officials just next door in Vermont began to wonder about the Saint-Gobain plant in their state. In February 2016, officials there announced results from tests of private wells in Bennington, Vermont. One of them came back at 2,880 parts per trillion.

The very next day, a director with Saint-Gobain placed a call to regulators with the state of New Hampshire. He wanted to let them know that the company had just detected PFOA in Merrimack’s drinking water.

Michael Hickey’s hunch about his dad’s death and his DIY testing had started a chain reaction. Without it, people in Merrimack might still not know about the PFOA in their water.

But what about everything Michael found when he first started researching? The news articles, that big scientific study? Where did all that come from? And why did it seem like nobody in New York knew about it? That’s coming up.

By the way, you can see photos of Michael, Hoosick Falls, and scroll through a timeline of all of this at our website, NHPR.org/SafeToDrink.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

[MIDROLL BREAK]

Hoplamazian, narrating: When I first started reporting on PFOA, it felt to me kind of like Sauron’s character in “The Lord of the Rings.” You never see his face, you don’t really know anything about his backstory – at least in the Peter Jackson movies. His presence on Middle Earth, the destruction he’s causing… it all feels kind of inevitable. I never really thought to wonder where he came from, why he is the way he is.

The industry that would end up contaminating the water in Hoosick Falls and Bennington, and Merrimack, it had a pretty unlikely start.

Roy Plunkett, oral history interview clip: The discovery of PTFE has been variously described as an example of serendipity, a lucky accident, a flash of genius. Perhaps all three were involved.

Hoplamazian, narrating: It was 1938. Roy Plunkett was at work in a lab in New Jersey owned by E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company. You might know it as DuPont.

Roy joined DuPont in 1935. He was helping them develop new kinds of refrigerants. This was during the rise of chloro fluoro carbons or CFCs – y’know, the stuff that depleted the ozone layer.

Roy told an oral historian that on an early April morning in 1938, he was experimenting with something called tetrafluoroethylene gas. But the experiment didn’t go as planned.

Plunkett: My helper said, "Hey Doc, did we use all of the gas in this cylinder?" And I said, "No, I don't think so." He said, "Well, it's, uh, nothing's coming out. I don't know what the heck is wrong."

Hoplamazian, narrating: The cylinder didn’t have gas inside. But the weight hadn’t changed, so there was something in there.

Roy turned it upside down and powder fell out. The gas had polymerized, the molecules all linking together. The tetrafluoroethylene gas had turned into polytetrafluoroethylene… PTFE.

When he started to test the powder he’d accidentally made, Roy saw that it was special. It was so strong. He couldn’t find anything in his lab that would dissolve it. It wouldn’t react with any other chemical.

DuPont shelved it. It was too expensive to manufacture. But then, the U.S. military came calling.

[MUSIC OUT]

Archival news clip: [FADES UP] As German troops swarm across frontiers in their first offensive since 1914… [FADES OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: It was World War II and they were trying to make an atomic bomb. Turns out, when you’re enriching a lot of uranium, you need something very, very durable.

According to Roy, the director of the Manhattan Project, Gen. Leslie Groves, learned about his invention.

Plunkett: And, uh, he said, “You guys better get a hold it and develop it or we're gonna take it away from you."

Oral historian: Mmm…

Plunkett: And that was about, about the way that… [BOTH MEN CHUCKLE]... the way that it went.

Hoplamazian, narrating: After the war, DuPont and other companies realized PTFE wasn’t just useful for nuclear bomb-making. It was resistant to the elements. It was extremely slippery. It could have all kinds of applications for consumer products.

So, they commercialized it. They called it “Teflon.”

[MONTAGE OF TEFLON ADVERTISEMENTS]

[SOUND OF OLD TV KNOB CLICKING]

Ad 1: A set of non-stick, easy-clean Teflon 2 certified cookware makes a beautiful…

[CLICK]

Ad 2: Just spray, bake, and slip away!

[CLICK]

Ad 3: Resolve carpet-cleaner with DuPont Teflon.

[CLICK]

Ad 4: …engine treatment with DuPont Teflon!

[CLICK]

Ad 5: Clorox and Teflon bring you… the non-stick bathroom.

[CLICK]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Roy Plunkett’s accidental discovery became a huge success. And before he died in 1994, of cancer, he got his kudos for it. Lots of awards. A member of the Plastics Hall of Fame.

Plunkett: I'm proud of my part in this development, proud of the company with whom I've worked, proud of what has happened, and most of all I'm proud of the benefit to mankind from this original invention.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: What makes Teflon so remarkable…almost magical is its chemistry. It’s made of a string of carbon and fluorine atoms bonded together.

Picture a caterpillar – the body is a bunch of carbon atoms, and the feet are fluorine. Now, picture a caterpillar with really, really strong legs. Those bonds between the carbon and fluorine atoms are the strongest single bonds in organic chemistry. That bond is what makes Teflon so resistant to the elements.

Not long after DuPont created Teflon, another company, 3M, created a similar chemical. PFOA. It also has that carbon-fluorine bond. PFOA was useful in the mass production of Teflon, so you’d often find them together.

Today, PFOA and Teflon are just two out of thousands of what we now call PFAS chemicals.

Remember their nickname… “forever chemicals.” “Forever” because they’re so strong, they can withstand breaking down for a long, long time. Studies project it would take thousands of years. And over that time, they can move around pretty easily in air and water and our bodies. I think of them like tiny little caterpillar ghosts, moving around in our world. The undead.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Starting in the 1950s, DuPont used PFOA to help make Teflon at a factory outside of Parkersburg, West Virginia. They kept it up for decades.

What happened next – the story of Parkersburg, West Virginia – is in some ways the original production of the play we’ve been watching.

It starts on a cattle farm outside of town. It’s right next door to a landfill used by the DuPont factory.

The farm is run by Wilbur Earl Tennant. Before there's Laurene Allen in Merrimack, or Michael Hickey in Hoosick Falls, there’s Wilbur. Another person who can just tell something isn’t right.

Wilbur Tennant, on camcorder video: [CAMCORDER ROLLING SOUND FADES UP] Somebody’s not doin' their duty. And they’re going to find out one of these days that somebody’s tired of it. [FADES OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: That’s Wilbur, in a series of camcorder videos he took in the mid-‘90s.

He’d lived and worked on his farm with his siblings since he was a child. He knew the land and he knew his animals. And he made these videos because there was something deeply strange happening to them.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: The creek that flows to his cow pasture has become frothy, like someone poured in bottles of soap. Wilbur zooms in on a dead fish that’s floating upside down.

Tennant, on camcorder video: When I told you I didn't see any minnies in this stream o’ water, this oughta tell you right yonder what I’m a-talkin’ about. Soon as they hatch out, they don’t live very long ‘til this water kills ‘em.

Hoplamazian, narrating: The cows drinking this water look terrible – emaciated and sick. Wilbur says they’re miserable, kicking and rolling around on the ground. And so many of them are dying.

In one video, he points the camcorder at a burn pile as he narrates. The body of a dead calf is in flames.

Tennant: [SOUND OF CAMCORDER ROLLING, BIRDS CHIRPING, AND FLAMES FADES UP] This is the hundredth-and-seventh calf… that has eh– that's met this problem right here… and I’ve burned ‘em all. [FADES OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: In some of the tapes, Wilbur is doing his own autopsies of the cows. In one, he zooms in on the cow’s teeth. They look rotten. In another video, he dissects the cow’s internal organs.

Tennant: I've never been into anything like it in my lifetime. Even the veterinarian been in it. He wouldn't ever saw anything like this before in his life either. [CAMCORDER ROLLING SOUND FADES OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Wilbur is convinced all of this has something to do with DuPont’s landfill next door.

Tennant: And as I said, it's been like this all along. The DNR, EPA, or nobody else in this state government wants to get up off their can and do anything about it. And if it’ll kill these minnies, what will it do to other stuff in this area?! [CAMCORDER ROLLING SOUND FADES OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: He’s determined to do something. So Wilbur reaches out to a fancy lawyer. His name is Rob Bilott.

Rob takes the case and he starts doing lawyer things. He doesn’t know exactly what is making the cows die, but he sues DuPont in 1999. And through the discovery process, DuPont is forced to hand over a mountain of internal documents about the chemicals they’re using.

Rob Bilott: Honestly, it took me a while to really understand what I was seeing.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Rob finds references to a chemical called PFOA. At DuPont, they also called it C8 – for the eight carbon atoms that make up the body of every PFOA caterpillar. Rob’s never heard of C8 before. It’s not on any list of regulated materials. But it turns out, the company has been dumping it at the landfill near Wilbur Tennant's farm.

That's just the beginning. What Rob finds next is so big, it will shape the debate around forever chemicals for decades to come.

Bilott: And what really struck me was seeing, you know, the DuPont company's own scientists, um… raising concerns about the potential cancer effects.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Scientists inside DuPont and 3M had been studying whether PFOA was toxic for decades. And a lot of what they found suggested it was.

[MUSIC IN]

Bilott: Not only did DuPont know that, but 3M the manufacturer knew that. And, you know, there was all of this internal data I was seeing suggesting here we had a chemical that looked to be pretty toxic, bioaccumulative, biopersistent – potential carcinogen!

[MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: 3M and DuPont had run all kinds of experiments with PFOA.

They tested it on rats. Some of them died. Others had problems with their livers, eyes, testicles, and kidneys. They tested it on dogs. Two beagles got doses of the chemical and then died within two days.

DuPont and 3M tested the blood of their employees. Based on what they knew about PFOA’s effects on pregnant rats, DuPont switched female employees at their West Virginia factory out of areas where they used PFOA.

By the 1980s, the companies knew the chemical was toxic to animals and they knew it was getting into human bodies and accumulating.

And in the case of DuPont in West Virginia, they knew as early as 1984 that PFOA wasn’t just getting onto Wilbur Tennant’s farm. It was leeching into the drinking water supply for tens of thousands of people in the Ohio River Valley.

[MUSIC OUT]

It’s a huge moment in the history of PFAS chemicals in America. So big, they made a movie about it. Wilbur Tennant’s lawyer, Rob Bilott, is played by Mark Ruffalo. Honestly, great casting.

Mark Ruffalo, “Dark Waters” film clip: [MOVIE MUSIC IN] DuPont knew everything. They knew that the C8 they put into the air and buried into the ground for decades was causing cancers… [FADES OUT]

Bilott: [FADES UP] …And as I'm looking through all of this, really not seeing any information being exchanged and disclosed with the government, with the regulators, with the scientific community, and certainly not with the public.

Hoplamazian, narrating: We reached out to 3M and DuPont with a lot of detailed questions about this.

3M didn’t respond to our questions, but they sent a statement about their, quote, “voluntary exit” from manufacturing PFAS chemicals and the billions of dollars they’ve paid in settlements to fund remediation efforts.

Reaching out to DuPont was more complicated. They’ve done a lot of restructuring. They created a new company called Chemours and stuck it with their PFAS liabilities. Chemours didn’t respond to our request for comment. The company now known as DuPont told me in a statement, basically, they have nothing to do with this.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Okay… Rob discovered DuPont and 3M knew PFOA might be toxic. But the companies didn’t tell the public. And they didn’t tell the EPA. So, Rob did.

In 2001, Rob sent a letter to the EPA and other government officials with what he’d learned. It was like Rob sending up a flare. All the health risks about PFOA that the companies knew but didn’t share, they were no longer a secret.

But meanwhile, local authorities in West Virginia sent out letters saying the water was still safe to drink.

[MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Rob filed a class action lawsuit against DuPont on behalf of the tens of thousands of people who were exposed to PFOA through their drinking water.

It took three years, but in 2004, DuPont settled the lawsuit. As part of the agreement, DuPont would pay for a new scientific study. The study would try to pin down whether PFOA could be linked to illnesses in Parkersburg and nearby towns. It would be called the C8 study after DuPont’s name for PFOA.

The team of scientists conducting the study were chosen by Rob AND DuPont together. Almost 70,000 people who had been exposed to PFOA gave blood samples. It was one of the largest epidemiological studies in history.

It took several years. A few years before it was published, Wilbur Tennant died.

Finally, at the end of 2011, the results started to come out.

[MUSIC OUT]

Bilott: They were able to confirm what, frankly, we had seen in the internal documents years earlier, but the companies were denying, which is that the chemical can in fact cause harm in humans. Six different diseases that were linked.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Six different diseases.

The scientists found probable links between exposure to PFOA and kidney cancer, testicular cancer, thyroid disease, high cholesterol, pre-eclampsia, and ulcerative colitis. The term “probable link” was defined this way. Quote, “Given the available scientific evidence, it is more likely than not that among class members, a connection exists between PFOA exposure and a particular human disease.”

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: The internal company research and animal experiments Rob had uncovered raised serious red flags. And now, there was a massive study to add to that. A study that said it was more likely than not that PFOA was making people sick. A study you could find at C8SciencePanel.org if you searched the terms “Teflon” and “kidney cancer.”

[MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: In the aftermath of all this Rob Bilott thought, “Okay, here we go. PFOA in the water, plus evidence PFOA causes bad things to happen to humans, equals… the government needs to make sure people stop drinking water with PFOA in it.”

Bilott: I remember going back again to U.S. EPA and saying, “Okay, now that we've gotten this data that’s pretty much definitely, finally confirmed what we’ve been saying for years, what else do we need to finally move forward and begin regulating these chemicals in the drinking water of this country?”

[MUSIC OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: But the EPA wanted more data, to find out how widespread the PFOA issue was before making any enforceable rules.

In the meantime, the EPA got DuPont and seven other PFOA manufacturers to start voluntarily phasing out the chemical by 2015.

They also created that health advisory guideline, 400 parts per trillion. Later, they revised it down to 70.

These might seem like victories for Rob. But year after year, the EPA didn’t do the one thing he really wanted – set a legally enforceable limit for how much PFOA was allowed in public drinking water.

And without a federal limit, whenever contamination was discovered in a new town, it was like someone hit “rewind” and started the story over.

Bilott: It’s almost as if everybody was starting from ground zero and trying to find out what do we know about this chemical? Is there any information about the health effects? Has anybody ever dealt with this before? Very frustrating because, ya know, here we had a situation where [LAUGHS] this had been going on for decades!

Hoplamazian, narrating: Rob watched this happen over and over. PFOA is discovered in a town and it’s like Parkersburg never happened. No one’s heard of PFOA. It’s an unregulated chemical, an “emerging contaminant.” Same play, different set.

[THEME MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: So, why does this keep happening? In Parkersburg, Hoosick Falls, Merrimack and other towns, too. Why doesn’t the story of this chemical stick?

Betsy Southerland: You will hear industry, their constant refrain is that each one of these 15,000 PFAS chemicals is, is like a snowflake.

Mike Wimsatt: You follow the science and that's, that's kinda your only– If you don't follow the science, then you're in the wilderness.

Hoplamazian, narrating: That’s next time on Safe to Drink.

[THEME MUSIC UP AND OUT, CREDITS MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Safe to Drink is reported by me, Mara Hoplamazian.

Additional reporting and production by Jason Moon.

Our editors are Daniela Allee and Katie Colaneri.

Editing help from Daniel Barrick, Rebecca Lavoie, Taylor Quimby, Elena Eberwein, and Lau Guzmán.

Fact-checking by Dania Suleman.

Legal review by Jeremy Eggleton.

Jason Moon wrote all the music you hear in this podcast.

Photos by Raquel Zaldívar.

Sara Plourde designed our website, NHPR.org/SafeToDrink, where you can also check out Rob Bilott’s letter to the EPA and documents he discovered through court cases and much more.

Nate Hegyi designed our logo.

Special thanks to Sharon Lerner, whose writing for The Intercept and ProPublica was very helpful when I was reporting this episode, and to Mariah Blake, whose book “They Poisoned The World” introduced me to people in Hoosick Falls.

Safe to Drink is a production of the Document team at New Hampshire Public Radio.

[CREDITS MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Full citations for archival images:

Roy Plunkett with Teflon insulated cable. DuPont Company External Affairs Department photographs (Accession 2004.268). 1990 (year approximate). AVD_2004268_P00000217. Series IV. People, Box 07, Folder 41, File number P-00000217, Audiovisual Collections, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, DE 19807.

Roy Plunkett (right) reenacts invention of Teflon. DuPont Company External Affairs Department photographs (Accession 2004.268). 1966. AVD_2004268_P00000214. Series IV. People, Box 07, Folder 40, File number P-00000214, Audiovisual Collections, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, DE 19807.