Former workers at Saint-Gobain’s New Hampshire plant share what they did — and didn’t — know about PFOA and its potential health effects. And how the chemical industry has worked to sow doubt to its own benefit.

Documents & Resources

We reviewed hundreds of documents for this project. We’ve included a few below.

- What Chemfab knew

These are the minutes from a March 14, 1995 Chemfab meeting where company officials discussed PFOA. This is a presentation given by DuPont to Chemfab and other customers that appears to be from between 1997 and 2000.

- What Saint-Gobain knew

This is a slide deck from a 2004 meeting about PFOA at Saint-Gobain. This is a memo from March 2006 describing Saint-Gobain’s Tymor team and its goals. This is a July 2006 message from Ed Canning, Saint-Gobain’s then-Director of Environment, Health and Safety, describing the Tymor team’s progress and blood testing plans, included as an attachment to a 2022 letter to the New Hampshire Attorney General’s office.

- Lawsuits against Saint-Gobain

These are the lawsuits filed against Saint-Gobain in New York, Vermont, and New Hampshire.

- Saint-Gobain’s letter to Ivan Soto

This is a letter from Saint-Gobain to Ivan Soto sent August 31, 2020 in which the company denies it sponsored PFAS testing for employees.

- Robert Bilott’s letter to NH regulators

This is the letter attorney Robert Bilott sent to New Hampshire regulators on March 8, 2016. In it, Bilott says the state’s announcement about PFOA contamination in Merrimack "ignores the vast wealth of published, peer-reviewed, and independent C8 Science Panel research.”

- The 2014 paper on PFOA referenced by NH’s Health Department

State Epidemiologist Dr. Ben Chan referenced this 3M-funded paper in his March 2016 remarks after PFOA was discovered in Merrimack’s drinking water.

- 3M science strategy documents

These are documents showing 3M’s strategy to direct the science and public knowledge of PFOA.

- Analysis of industry influence

This is a 2023 paper published in the Annals of Global Health that analyzes the influence of the chemical industry on PFAS science.

Transcript

Mara Hoplamazian, narrating: Over the past year, I’ve talked to a half-dozen people who worked in the Saint-Gobain plant.

I wanted to understand what this story looked like for them. No one was closer to PFOA, the chemical that contaminated Merrimack’s water, than the people who used it every day.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: In the last episode, we talked about 3M and DuPont, companies that made Teflon and PFOA. Saint-Gobain was a customer of those companies. They bought chemicals and used them to make their own products.

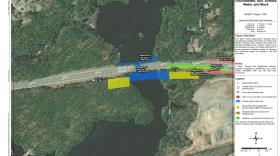

In Merrimack, Saint-Gobain was using the chemicals to coat textiles. The Merrimack plant itself was a huge rectangle – more than two-and-half football fields long. And tall, says former worker Kenny Blaha.

Kenny Blaha: It was imposing. It was like four, four and a half stories tall. I mean, just this very tall building for what it is.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Brian Cloke, another former worker, says the building had to be tall to fit the machines they were working with inside.

Brian Cloke: It was intimidating due to the sheer size of the machinery, but the concept was easy enough to follow.

Hoplamazian, narrating: The concept was this – Workers would feed huge rolls of fabric into the giant machines. As the fabric unspooled, it would go through a tray with a milky liquid in it. Workers called the liquid the “dispersion,” a mix of water and chemicals like Teflon and PFOA.

Blaha: So, you'd have a roll here paying out material. It would pay out into the dispersion tank where it would get coated.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Then, the coated fabric would be pulled up into a long vertical oven that could get up to 750 degrees. After it was coated, workers would cut and assemble the fabric into their final products. In Merrimack, they made everything from HAZMAT suits and chemical hazard shelters to nonstick conveyor belts for fast food restaurants.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: A lot of the people I talked to said there was something satisfying about the work. They liked building things, things that might save lives.

Saint-Gobain handled a lot of military contracts. The projects felt important. Kenny Blaha helped install big radar covers in some pretty cool places.

Blaha: You know, I got to be in the, in the midnight sun in the Arctic. I got to go to Kwajalein where there's a destroyer in the middle of the, the ring, the atoll, just still sitting there from World War II. Ya know, got to do the Blazin’ Challenge at a bunch of different Buffalo Wild Wings across the country. [BLAHA, HOPLAMAZIAN LAUGH]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Talking to these guys, I got the sense most of them were a little amused by the questions I was asking about their old jobs. Like, “Yeah, we know, this work comes with exposure to powerful and dangerous chemicals.” But, as Josh Lovett told me, that’s the job.

Josh Lovett: I was like, I worked at a warehouse. What can I, ya know what I mean? That's what happens when you're the bottom of the barrel and you gotta go work at the plant. You get exposed to all the chemicals that other people don't have to deal with, and somethin’s gonna happen, ya know?

Hoplamazian, narrating: It wasn’t like they didn’t have any worries. Those massive vertical ovens released a lot of smoke. It was supposed to be vented out the roof of the building through stacks. But everyone said a lot of that smoke stayed inside of the building, sometimes creating a thick haze.

Cloke: We would notice, almost like walking into fog, like on a foggy night, even as we were walking down the, ah, hallway to get to the production floor.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Sometimes workers would get sick from the air inside of the building. Some people called it “Teflon flu.”

Blaha: It feels like one of the worst flus you've ever had. You jus– It just suddenly hits you [SNAPS FINGERS] with a, with a really hard fever.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Everyone I talked to remembered getting some kind of personal protective equipment to wear like masks, paper smocks, and gloves. But how seriously people took that protective equipment seemed to vary.

John McLaughlin got a job at Saint-Gobain right after he got out of the Marine Corps. He told me the coworkers who trained him warned him it was not going to be a tidy experience.

John McLaughlin, on the phone: They just said, ya know, “You're working in the coating department. It's a dirty job. You're gonna get covered in the Teflon. You're gonna have it on your clothes, your boots, your hands a lot.” They're like, “If you smoke or use smokeless tobacco” like I did at the time, they said, “You got to wash your hands with the two different kinds of soap to get most of it off.”

Hoplamazian, narrating: Sometimes, John says, the dispersion would also end up on the ground, like when he would clean sheets of metal that sat inside the big vertical ovens.

McLaughlin: And we'd powerwash it outside in the parkin' lot, a-and there was no slop basin or nothing to pick it up. It'd just be blowin’ off into the sunset or all over the ground, right into a drain or somethin’.

Hoplamazian, narrating: We asked Saint-Gobain about all of this – the smoke in the factory, Teflon flu, the parking lot powerwashing. The company didn’t answer our questions, but sent a statement saying, quote, "ensuring the health and safety of employees is paramount to Saint-Gobain and is core to our culture," unquote. They also said the company, quote, "strives to meet or exceed applicable regulations," unquote.

It seems like for most people there was no big a-ha moment. No day when PFOA started setting off alarm bells, when they started to think, “Huh, maybe one of these chemicals is different from the others.”

But a few of the former workers told me, something did feel off. Micah Holmes said it was a feeling that built up slowly over the 16 years he worked there.

Micah Holmes: The job market at the time at that area was kinda tricky. Um… I was stuck. I was stuck doin’ a job that I didn't really wanna keep doin’, and I was watching as one by one, my coworkers were either suffering something or moving on to other things and not coming back, and… I hear later they passed on.

[THEME MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: I wanted to talk to people who worked at Saint-Gobain to understand what it was like there. They were closest to these chemicals, face-to-face with the stuff that contaminated a whole community – for many workers, the community they lived in.

I was also hoping they’d be able to tell me what the company knew about PFOA before the contamination became public. But our conversations ended up raising even more questions.

For one thing, many workers told me they had no idea about PFOA for a lot of the years they worked there or that it could be harmful for people living nearby.

Kenny told me he was surprised when he learned people in Hoosick Falls had been getting sick from PFOA. He said most of what he learned about the chemical he’d worked around for years came from a segment he saw on The Daily Show and a documentary he watched after he left the job.

Blaha: Ya know, I didn't want to be pumping those fumes into the air, into the drinking water, into the wells, into the ground. We didn't want that, hmm? We didn't know. We really didn't know. The people that were rank and file. You know. And it wasn't… It was hidden. It was hidden not just from us – it was hidden from everybody.

[THEME MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: So, what about the higher ups at Saint-Gobain? What did they know about PFOA contamination and its impact on human health? When did they know it? And what did they do about it?

From the Document team at New Hampshire Public Radio, I’m Mara Hoplamazian. This is Safe to Drink.

[THEME MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: To find out what Saint-Gobain knew, we have to go back to the 1980s because before the plant in Merrimack, New Hampshire belonged to Saint-Gobain, it was owned by a company called Chemical Fabrics Corporation.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Chemfab, for short.

[MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Chemfab bought the Merrimack plant in 1984. Their big thing was Teflon-coated fabric roofs for sports stadiums and shopping malls and hotels.

Remember how DuPont and 3M were collecting information about PFOA? Doing all those tests on rats and dogs and their own workers? They didn’t share any of that information with health officials or regulators… but they did share some of that information with Chemfab.

So, here’s what Chemfab knew. They knew that PFOA caused birth defects when given to lab rats. They knew that PFOA didn’t break down in the environment. And they knew that it was being found in human blood. They also knew about Teflon flu, that exposure to Teflon as it was burned could cause workers to get sick for a few days.

[MUSIC OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Chemfab didn’t exactly ignore this information. In the ‘80s, the company commissioned a study of their own workers. It found an association between PFOA and erectile dysfunction.

And in the ‘90s, Chemfab and DuPont had meetings where they discussed what might replace PFOA. DuPont was trying to find an alternative because the chemical was so toxic.

But then, Saint-Gobain, this massive French company, bought Chemfab in 2000. And, well, it’s hard to say how much of this information got passed along.

The person in charge of knowing this kind of stuff is Ed Canning. He was Saint-Gobain’s environment, health, and safety manager.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: I tried to talk to Ed. We had a short phone call. He was very polite, but he didn’t want to do an interview.

We do know a little bit from him, though. In 2019, Ed gave testimony as part of a deposition. And during his deposition, he said when Saint-Gobain took over, Chemfab claimed that all the PFOA in that milky dispersion liquid got burned up in those huge ovens. That none of it was leaving through the stacks on the roof of the plant.

So, Ed said, when Saint-Gobain bought Chemfab in 2000, they had no reason to believe there was a risk to the surrounding community.

[MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: But then, just one year later, in 2001, public scrutiny around PFOA ramped up. Remember, that’s when Rob Billott – the lawyer from the last episode – got those smoking-gun documents showing DuPont and 3M knew exposure to PFOA could be unsafe and he told the EPA about it.

So, even if Chemfab hadn’t told Saint-Gobain what they knew about PFOA, a lot had just been made public. And Saint-Gobain was watching, aware that they might also get sued.

Ironically, we only know this because eventually, Saint-Gobain was sued and their internal company documents were made public.

[MUSIC OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: I spent months combing through those documents. One of the things they show is that in 2003, Saint-Gobain created a special team at senior levels of the company, led by Ed Canning. They gave it a code name – Tymor. T-Y-M-O-R.

Why did they call it Tymor? No idea. But from what I can tell, the team’s mission was to make sure this PFOA thing didn’t blow up in the company’s face.

They tracked media coverage of DuPont and Teflon closely. They developed standby statements in case Saint-Gobain got any questions from reporters or from their own customers. And they tightened PPE guidelines for workers.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Maybe the most significant thing the Tymor team did is they tested the information Ed Canning says the company got from Chemfab, that PFOA wasn’t leaving Saint-Gobain’s factories through the stacks.

Spoiler alert: It was. In 2004, the Tymor team confirmed that the Merrimack plant was releasing PFOA into the air. It wasn’t all burned off in the ovens like Ed Canning says Chemfab had told them.

Saint-Gobain reached out to New Hampshire’s Department of Environmental Services and told them the news. The state was like, “Well, how much are you emitting?” And Saint-Gobain said, basically, they didn’t know. They also said to find out would cost so much money, it might force them to close the plant.

For the record, Ed Canning told the regulators testing all 15 coating lines at the Merrimack plant in 2005 would've cost them $100,000 a pop, about $1.5 million total. I wondered how much that would eat into the company’s bottom line. That year, Saint-Gobain reported a net income of about $1.5 billion. That means they were making $1.5 million roughly every eight hours.

[MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: So, to recap. Saint-Gobain knew they were emitting PFOA into the air in Merrimack as early as 2004. Those emissions had likely been happening for decades since Chemfab started production in the 1980s. But Saint-Gobain didn’t know how much PFOA was getting out of their stacks. And they weren’t willing to pay to find out.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Eventually, New Hampshire and Saint-Gobain reached a compromise. Saint-Gobain agreed to switch to a “low-PFOA” dispersion by 2006 – a new recipe for that milky liquid that had a lot less PFOA in it.

But throughout all those years – even after contamination was discovered in the water around Parkersburg, West Virginia and Rob Billott exposed what DuPont and 3M knew – there’s no evidence that anyone in New Hampshire stopped to ask… could the same thing that happened in Parkersburg be happening here? Could PFOA from the Saint-Gobain plant be getting into the drinking water?

So, people in Merrimack drank the water. They used it to boil pasta and water their gardens. They poured it into their dog bowls and mixed it with Kool-Aid powder for their kids' playdates… for another decade.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: I asked Saint-Gobain when they first became aware the plant was releasing PFOA into Merrimack’s water and whether they discussed testing drinking water before the contamination in Hoosick Falls became public.

In a statement, a company representative said any PFOA used in their facility came from raw materials they bought from suppliers – suppliers they were relying on to follow industry laws and regulations. The company also said, quote, “While it is well known that PFAS has been used in a wide array of products and despite other industrial sources in the area, Saint-Gobain remains committed to extensive remediation efforts,” unquote.

[MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: There’s no document we’ve found or interview we’ve done that shows Saint-Gobain knew they were contaminating the drinking water of the communities they operated in.

But today, some of the former workers I talked to are still skeptical that the company didn’t know more than they let on. One reason for that skepticism… is the blood tests.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Three of the former workers I spoke with were at Saint-Gobain in the aughts, when the drama in West Virginia was playing out. All of them remembered the company discussing blood testing with employees and two of them said they had their own blood drawn while they were at work.

John McLaughlin says at least once, he remembers his supervisor telling him to shut down the machines and go into the parking lot. A truck came. John calls it the “blood truck.” He doesn’t remember who was running the blood truck. He says a random nurse stuck him with a needle.

McLaughlin, on the phone: They never really told us what they were testing for.

Hoplamazian, narrating: John says he didn’t really think twice about it.

McLaughlin, on the phone: I was still in the military mindset of, ya know, willing obedience to all orders given. I just did it 'cause I was told to do it. Never questioned it.

Hoplamazian, narrating: He says the company never shared the results of his blood tests with him.

I talked to another former worker about this. His name is Ivan Soto. Ivan worked at the Merrimack plant longer than anyone else I met – for more than two decades. He started right before Saint-Gobain bought it in 2000. And he worked in lots of different parts of the plant. One of his main jobs was building HAZMAT suits and packing them up to ship to customers.

Ivan Soto: Put the visors, the gloves, testing repair. Package it. Send it to the customer.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Out of everyone I spoke with, Ivan had the strongest feeling that something wasn’t right at Saint-Gobain.

He comes off as kind of a teddy bear. The first time we met, he was wearing one of those “my favorite kid bought me this” kinds of t-shirts.

But Ivan is not afraid of confrontation. He spoke up about things he was seeing, especially after DuPont was fined by the EPA in 2005 for neglecting to share information about PFOA. Ivan told me he developed a reputation. People called him a troublemaker. He sees it more as a worker’s rights thing.

Soto: You have a right to ask questions for everything around you, everything around you.

Hoplamazian, narrating: So, when Ivan says the company took his blood and told him the test was routine. He didn't buy that. Ivan said when he sat down with the nurse who had the needle, he asked, “How can this be routine?”

Soto: She told me, “I don't know what's going on. They just told me to take out the blood samples.” “Okay, go ahead.” But they never give you the results, never explained why.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Ivan didn’t settle for that. He asked the company’s HR department for his test results. They said he had to wait for them to be sent to his house. But, he says no test results ever came.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Years later, he went to HR again, asked if they could look in his files and find his test results. Ivan says a woman with the company’s HR department told him she didn’t know what test he was talking about. Ivan couldn’t believe it.

Soto: I said, “What?!” I said, “You better be kidding me! You take my blood just for fun?” I said, “I want the result of my test.” They never give you to any – not to me, to any single employee down there. Never give it to us!

Hoplamazian, narrating: Then, in 2020, he spoke at a public hearing. It was more than a decade after Ivan says the blood testing happened and he still hadn’t gotten his results.

The hearing was kind of technical. Saint-Gobain was applying for an extension on a regulatory deadline. But Ivan had his own agenda. He told New Hampshire state regulators that the company didn’t care about its workers.

Soto, at hearing: I wanna know why that company is so powerful. Saint-Gobain polluted the town of Merrimack. It's just… it's something wrong here. I just, uh, I don't get it. They don't care about the workers.

Hoplamazian, narrating: He says, “I want to know why this company is so powerful. There’s something wrong here. I don’t get it.”

But the state officials don’t have any answers for him either. They don’t even really acknowledge what he’s saying.

Official, at hearing: Sir, you've, uh, you've reached, uh, well over five minutes now. Um, I think it's safe to say that you, uh, oppose the variance. Um, uh… but your comments are rather wide-ranging.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: After Ivan spoke at that meeting, he seemed to catch Saint-Gobain’s attention.

The company sent Ivan a letter saying that there was no company-sponsored blood testing at the factory. In the letter, they told him the Department of Health and Human Services conducted tests around 2007 and the company didn’t have access to the results.

But here’s where it gets weird. We reached out to both New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services and the United States Department of Health and Human Services to confirm this. And both say they were not testing Saint-Gobain workers in 2007.

Even weirder… a few years ago, I asked Saint-Gobain if they were testing employees' blood for PFOA. They told me the company did maintain what they called an industrial hygiene program, which included voluntary blood tests for employees in Merrimack. They said the results were protected health information of their employees.

So, two workers say their blood was taken and they never got their results. Another worker, Micah, says he remembers a meeting from 2005 where a man in a suit who worked for DuPont talked to workers at the plant about PFOA.

Micah Holmes: This guy was tellin' us, “Okay, it's inert, it does this. But what we're gonna do is we're gonna take a sample of 50 people. We're gonna aim for the people that are most, most of you are the closest exposed, you know, the actual workers using it.”

Hoplamazian, narrating: I asked Saint-Gobain about all of this again recently. About that meeting with DuPont, about the blood tests, about why their workers say they never got results. They sent me a long statement about the water remediation they’ve done, but they didn’t answer those questions.

To this day, I still can’t say for sure what was going on. But there is one internal company document that came out in one of the lawsuits against Saint-Gobain that I need to mention. It’s a document from the Tymor team, describing one of their objectives for their work on PFOA in the year 2006.

It was a plan to test employees’ blood.

[MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: You can read that document, the letter Saint-Gobain sent to Ivan, and much more at our website, NHPR.org/SafeToDrink.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

[MIDROLL BREAK]

Hoplamazian, narrating: What about the people who were supposed to be watching over all of this?

Every time I read a paper that described rat and dog and monkey deaths from PFOA exposure or I talked to a former Saint-Gobain employee about Teflon flu, I was like, “Why wasn’t this enough for regulators to act on?”

This has been one of the hardest things for me to understand about this whole story.

There was so much data. DuPont and 3M had studied this chemical for decades. Then, there was the C8 study based on the blood samples of almost 70,000 people in the Ohio River Valley, one of the biggest epidemiological studies ever that resulted in peer-reviewed articles that confirmed links between PFOA and six illnesses, including some cancers.

But year after year, PFOA remained an unregulated chemical, an unregulated chemical that lots of people were drinking.

From what I’ve gathered, there are two main reasons for that. Here’s the first.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: While attorney Rob Bilott was trying to bring the dangers of PFOA to light, the chemical industry was at work on its own project.

Rob Bilott: Part of the problem was you had companies that were actively pushing back and telling the regulatory agencies, “The science is still disputed.”

Hoplamazian, narrating: DuPont and 3M did not respond to our questions about this. But the companies have settled lawsuits, collectively paying out billions of dollars. Neither have ever publicly admitted that PFOA is harmful to humans.

And over the years, they've worked to cast doubt on the growing evidence that the chemical they created was making people sick.

For a long time, that doubt seemed to creep into the statements government officials were sharing, too.

Bilott: You had these companies and their consultants, ya know, these hired experts that were being brought in and set up in meetings with different state agencies to help, quote, “explain the science” to them, um, that were frankly, um, ya know, misleading the agencies.

Hoplamazian, narrating: When PFOA was found in Merrimack’s water, the state of New Hampshire said the research on PFOA and human health was inconclusive and more research was needed.

Remember, that was in 2016, four years after the C8 study ended.

Rob Bilott wrote a letter to those New Hampshire officials, telling them they were spreading inaccurate information, ignoring the, quote, “vast wealth of published peer reviewed and independent C8 science panel research.” He said the public should not be told the water was safe to drink.

But then, just a couple weeks later, the state held that big town meeting in Merrimack.

Woman, at 2016 Merrimack meeting: Can I drink the water? Can my pregnant patients drink the water? [APPLAUSE, FADES OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: And despite Rob’s letter, it didn’t sound like the officials had changed their tune very much.

Dr. Ben Chan, at 2016 Merrimack meeting: So, the big question here is what does finding PFOA in the water mean for our health, your health, the health of your loved ones. The, the quick… answer is that the long term health effects, uh, are really unclear.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Ben Chan, the state epidemiologist, did describe the C8 study in his presentation. He said it didn’t represent scientific consensus.

And then, he presented another academic paper. One that reviewed studies of PFOA and its health effects. That paper concluded there’s no evidence that would support the hypothesis that PFOA causes cancer. Chan called it a “very good” review.

Chan: The, the toxicology review noted that most evaluations have shown no association between PFOA and various cancers and that positive associations have been weak.

Hoplamazian, narrating: His slide deck had a screenshot of the article and included a note that it was funded by 3M.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Why does that matter?

You might be familiar with the idea of industry-backed research from tobacco companies. Starting in the 1950s, that industry hired scientists and paid for studies to challenge the idea that cigarette smoke was linked to health effects. A tobacco company executive wrote in a 1969 memo, “Doubt is our product.”

Other industries have taken a page from the same book. Industry-funded research looking at links between Agent Orange and prostate cancer or pesticides and Parkinson's concluded there wasn't convincing evidence of cause and effect – more research was needed.

[MUSIC OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: There’s another thing that these studies I just mentioned have in common… Agent Orange and pesticides. The scientists who authored them were the same scientists behind the PFOA study New Hampshire officials presented at that town meeting – the same exact people.

Five scientists on the PFOA study had already all worked together on the Agent Orange study. At least three of them did research for the tobacco industry throughout the 1990s and early 2000s.

The lead author of the PFOA study wrote several papers funded by chemical companies and trade associations. Sometimes the sponsors were allowed to review drafts of the articles. And in many of those papers, the conclusions sound the same – the health effects are uncertain, more research is needed.

Chan, at 2016 Merrimack meeting: So, in summary, there's a lot of uncertainty, unfortunately, about what we know about PFCs and the effects on health. Uh, this is perhaps a, a difficult area to operate in and frustrating.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: I reached out to New Hampshire’s health department multiple times, hoping to talk to Ben Chan or anyone there about their use of this 3M-funded study. They never responded.

I also reached out to the lead author of the 3M-funded study. Her name is Ellen Chang. We did a phone interview, but we agreed not to use her voice.

Ellen acknowledged that funders can have influence over research. But she said 3M didn't direct her to come to a specific conclusion. And she said her paper was in line with another independent review of the science on PFOA that was done around the same time.

That review from 2014 said PFOA was possibly carcinogenic. Ellen's paper said there was no evidence to support the hypothesis that PFOA causes cancer.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: So, there are these industry-funded studies that are making the scientific conclusions more confusing in ways that benefit companies making chemicals.

But here's the second reason it’s taken so long to deal with PFOA in drinking water.

I talked to Mike Wimsatt about it. He’s been at New Hampshire’s Department of Environmental Services, kind of like the local EPA, for almost 40 years.

He was a big part of the state’s response to the Merrimack contamination – such a big part that one of his kids etched the chemical formula for PFOA into a drinking glass for him.

Mike Wimsatt: It's really just, uh, it's dominated our work. It's kind of eaten our lunch for 10 years now.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Mike told me regulators have to do a really complicated balancing act.

If they required every possible contaminant to be filtered out, it would bankrupt most local water systems, which at the end of the day, are there to make sure we don’t all get cholera.

Wimsatt: If we say, “Okay, if you got any of these contaminants at any concentration, you shouldn't drink the water,” there'd be no water left to drink. Or if it were, it would have to be so heavily treated that it would be prohibitively expensive to provide it.

Hoplamazian, narrating: So, Mike says, we can’t just set all the limits at zero and say “problem solved,” especially when there’s science that shows many contaminants are safe to drink below certain levels.

Remember, the dose makes the poison, like, according to the EPA, a little bit of arsenic in your water is actually okay.

With PFOA, things were especially tricky. Mike says in 2016, it wasn’t on his radar. It wasn’t regulated and he says it’s very different from other chemicals. He was used to dealing with contaminants measured in parts per billion. So the idea that PFOA could be a problem in such tiny amounts as parts per trillion… it was strange.

And it was humbling. Mike thought his team had been doing a good job, prioritizing their work in the right way. And then, he found out they had missed what he called the largest drinking water contamination in New Hampshire's history.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Mike says New Hampshire started pressuring federal regulators to come up with an enforceable standard, so that they’d have a solid number they could use when trying to get Saint-Gobain to investigate and when talking to the public.

He still remembers the questions he got during that town meeting in 2016. He says it was really hard not to be able to give people clear answers about the potential risks to their health.

Wimsatt: That's why people don't like scientists sometimes because they caveat everything. They never make… blanket, black and white declarations. It's always a gray. And people hate gray, right? But the world of a scientist is a gray world.

Hoplamazian, narrating: “The world of a scientist is gray.” But whether the government says water is safe to drink or not is black and white. So, the question becomes how much proof do we need to act decisively?

It’s a question that Betsy Southerland has been thinking about for a long time.

Betsy ran the science and technology office at the EPA’s National Water Program until 2017. Part of her job was coming up with the levels of pollutants that could be in the air, soil, and water in the entire country.

And Betsy says, looking back, she gets why people feel like the EPA didn’t do its job quickly enough. She thinks the EPA’s regulation of PFAS chemicals was a public health failure.

Betsy Southerland: I’m heartbroken because I think that public health protection requires us to be much less risk averse and the “risk averse” is over litigation.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Betsy says it’s not as easy for regulators to act as the public might think. Regulators have to worry about their decisions holding up in court. Companies that use a regulated chemical can sue if they think EPA has gotten a limit wrong. And Betsy says if there’s any ambiguity about health impacts, the regulation could get struck down.

Southerland: You wanna protect the public and you don't want to insist on thousands of studies not being enough, 10,000 studies not enough, 100,000 studies not enough. And yet today, I can tell you there are scientists out there working for industry who will say it's very questionable as to whether even PFOA or PFOS are carcinogenic.

Hoplamazian, narrating: You might remember that in 2006, in the wake of the contamination in Parkersburg, West Virginia, the EPA got DuPont, 3M, and other manufacturers to promise they would phase out two PFAS chemicals, PFOA and PFOS.

Betsy says the problem is the companies just started making new kinds of PFAS chemicals. Nowadays, by Betsy’s count, companies have created more than 15,000 of them.

Southerland: You will hear industry, their constant refrain is that each one of these 15,000 PFAS chemicals is, is like a snowflake. It's entirely different from each of the other 15,000 PFAS chemicals. Each one must be studied individually and exhaustively, uh, before they will agree that they need any regulation at all.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Betsy says it takes the EPA about seven years to study one new chemical. If you’re curious about the napkin math, that comes to 105,000 years.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: There are some efforts to streamline that process. And other countries have different ways of managing this problem. Like in the European Union, chemicals aren’t innocent until proven guilty. Companies have to register their chemicals and submit safety data before they’re allowed to be sold.

But in the U.S., until the federal government finds a more efficient way to regulate PFAS chemicals or companies decide to stop making them, Betsy says state regulators are going to have to handle things on their own.

Southerland: The only hope is that states will have so many of these individual communities that are so terribly burdened with incredibly high levels of PFAS that the states will move out on individual locations with these problems.

Hoplamazian, narrating: She’s hoping communities will convince states to act without waiting for the EPA.

In many ways, that’s exactly what happened in New Hampshire. Mike Wimsatt says state regulators learned a lot from what happened in 2016.

Wimsatt: And we're like, "Okay, we're gonna… It's a shame that we didn't know about this earlier, but we're not going to be caught flat-footed. We're gonna go out there and do everything we can to make sure we understand."

Hoplamazian, narrating: In the years after PFOA was found in Merrimack, New Hampshire regulators would go on to set one of the lowest PFOA limits for drinking water in the country – 12 parts per trillion. They also required water systems across the state to test for PFOA and they got sued for doing that by a local water system and by 3M.

Wimsatt: Ya know, that, that just goes with the territory, but you can't be afraid of that. You just, you follow the science and that's, that's kinda your only… If you don't follow the science, then you're in the wilderness.

Hoplamazian, narrating: 3M eventually dropped the lawsuit. New Hampshire kept testing water. By 2025, state regulators would test more than 15,000 wells.

When you look at a map of PFOA in water across the U.S., New Hampshire looks really contaminated compared to other states. But Mike says… that’s just because they’re looking.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Where does all of this leave the people who've already been exposed?

John McLaughlin, one of the former workers who says he had his blood tested in the early 2000s and never got the results, went in for a regular physical in January 2025. He’d just started seeing a new doctor. She hooked him up to a monitor and saw his blood pressure was high – really high.

McLaughlin, on the phone: She's like, "It's 250 something over 171." Put me on an EKG. "You're actively havin' a heart attack."

Hoplamazian, narrating: John was rushed to a hospital. There, they discovered he also had kidney damage.

McLaughlin, on the phone: Wasn't experiencing anything major except, like, weird back pains once in a while and she's like, "Yeah, that's usually an indicator you're having a kidney issue."

Hoplamazian, narrating: He’s on some meds now. They’re helping. And after a few months of trying, he got his insurance and the VA to approve blood tests so he can get the answers about what’s in his body that he says Saint-Gobain never gave him. He’s hoping his results will help his doctors mitigate his risk of cancer.

McLaughlin, on the phone: I just wanna get to the bottom of everything, ya know?

Hoplamazian, narrating: John says some of his former colleagues have gotten sick and some have died – so many that he says one of his work friends started collecting peoples’ obituaries in a photo album.

McLaughlin, on the phone: Ya know, it's kinda like, yeah, so, um… What exactly did I get myself into? And… and kinda like, what am I supposed to expect later in life?

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: I heard some version of this question from all of the former workers I spoke with. Ivan said when his kids were young, he worried about bringing his clothes home from work after being in the smoggy building all day.

Ivan Soto: My daughter was, what, 2 years old? My son was 4. And I was just start… build my family. Like I said, I work in the company. I bring my clothes home. It was kinda, you know, naggin' back in my head. Can't do the right thing. Ah, it's just tough.

Josh Lovett: I'm not gonna lie, the air quality had me really concerned about my longevity 'cause there are people that have been workin' there for 20 years, and they just, they're hackin' like you've never heard in your life.

Micah Holmes: And I'm goin', [THUMPS HAND DOWN] "Am I next? What am I doin' that will make me next? Holy shit!" And you start thinking and you start worrying and the stress starts to build.

Kenny Blaha: Maybe on some level, I don't want to know if… ya know, if I've got elevated levels in my blood. Maybe I don't want to know. Maybe they don't wanna know. Maybe I'm afraid to find out… Yeah… That's somethin', that'll take me a long time to get to the root of that one…

[MUSIC OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: When you know you’ve been exposed to a chemical that's probably harmful, what can you do with that knowledge?

[THEME MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: And how do you move forward when you can’t trust something as basic as your tap water?

Loreen Hackett: All I could think of was, "Well, if you won't hear us, all our yellin', you're gonna see us."

Wendy Thomas: You know, a lot of people ask me, "Why haven't you left? Why haven't you gone someplace safer?" And it's like, if I leave, who is going to be staying here to fight?

Hoplamazian, narrating: That’s next time on the final episode of Safe to Drink.

[THEME MUSIC UP AND OUT, CREDITS MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Safe to Drink is reported by me, Mara Hoplamazian.

Additional reporting and production by Jason Moon.

Our editors are Daniela Allee and Katie Colaneri.

Editing help from Daniel Barrick, Rebecca Lavoie, Taylor Quimby, Elena Eberwein, and Lau Guzmán.

Fact-checking by Dania Suleman.

Legal review by Jeremy Eggleton.

Jason Moon wrote all the music you hear in this podcast.

Photos by Raquel Zaldívar.

Sara Plourde designed our website, NHPR.org/SafeToDrink, where you can check out court documents from cases involving Saint-Gobain, a drawing of the ovens in the Saint-Gobain plant, the letter Rob Bilott sent to New Hampshire, and much more.

Nate Hegyi designed our logo.

Safe to Drink is a production of the Document team at New Hampshire Public Radio.

[CREDITS MUSIC UP AND OUT]