A New Hampshire town finds out its water has been contaminated by a “forever chemical.” The source appears to be the nearby Saint-Gobain plant. Officials say the potential health effects are unclear, but most people can still drink the water. One resident doesn’t buy it and goes down a research rabbit hole. She soon learns all this has happened before.

Documents & Resources

We reviewed hundreds of documents for this project. We’ve included a few below.

- The email to state regulators

This is the email Ed Canning, Saint-Gobain’s then-Director of Environment, Health and Safety, sent to New Hampshire regulators on Feb. 26, 2016 — the day after Vermont announced it had detected PFOA in private wells near the company’s North Bennington plant. NHPR obtained this email through a right-to-know request.

- The press release

This is the press release the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services sent out the following week on March 4, 2016, announcing that PFOA had been detected in samples of drinking water from Merrimack’s public water system.

- Saint-Gobain’s response

This is an April 13, 2016 letter from Saint-Gobain to New Hampshire state regulators. While it does not admit any liability, the letter outlines the steps the company initially agreed to take “to ensure that residents living near Saint-Gobain's Merrimack facility… have drinking water without elevated levels of PFOA.”

Transcript

Mara Hoplamazian, narrating: Ben Peirce was driving home. He’d just dropped his kid off at daycare. And he noticed something kind of odd.

Ben Peirce: I remember coming down High Range Road and passing one of the neighbors houses up on High Range Road, and they were getting a water delivery.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Like, cases and cases of bottled water. The kind of delivery you’d see at a convenience store.

Peirce: And I remember just thinking like, “Wow, they really love the bottled water there! Like, I'm surprised that they have, like, special delivery of bottled water to their house.”

Hoplamazian, narrating: Ben’s family had just moved to Londonderry, a town in southern New Hampshire, in the summer of 2019. Now it was October. Ben was still new in town. The water thing was weird… but whatever. He kept driving.

Peirce: And I came around the circle and I drove down to our house and sitting right in our driveway was a whole massive pallet of water. Um, no explanation, no delivery person. It was just sitting there in the driveway.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Later, Ben did the math. Someone had delivered roughly 2,700 gallons of water to his house.

Hoplamazian, off mic: There wasn’t, like, a note?

Peirce: There was nothing, no. And I just assumed it had to be a mistake.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Ben remembered the delivery truck he saw. He decided to try and catch up to it.

Peirce: So, I hopped back in the car and I drove around the block and I said, [LAUGHING] “Hey, um, I don't know if you made a mistake, but there's all this water in our driveway. We didn't order any water.” Um, and he kind of sheepishly said, like, “Oh, you don't know about this…?”

[MUSIC OUT, CREEPY TONE IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: For a lot of people… the Peirces, me, maybe you… tap water is a given, like the sky being blue or pavement being solid. Turning on the tap is a reflex, almost like breathing.

[MONTAGE OF WATER SOUNDS]

Hoplamazian, narrating: We do it when we shower. Fill the coffee pot. Boil pasta. When we brush our teeth.

After the surprise delivery, Ben made a few calls. And he discovered that the water he and his family had been using for months had something in it. Something that made it unsafe to drink or to cook with. Something you couldn’t boil out.

[WATER SOUNDS UP, THEN ABRUPTLY OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: So, instead of turning on the tap, they started cracking open plastic bottles. They explained to their two young kids, “Don’t drink out of the faucet. Don’t even use it to rinse your toothbrush.” One of the things Ben worried about most was the teeth brushing, especially with his 3-year-old, Kinsey.

Peirce: You know, it was a lot for her to just even manage a tube of toothpaste and a toothbrush, you know? So, to then ask her to… you know, unscrew a cap and pour a little bit of water on her toothbrush and then, you know, uh… I really didn't think they'd be able to do it as kids.

Hoplamazian, narrating: They still used the tap for showering, but tried hard not to get the water in their mouths. They still used the sink for washing plates, but dried them off extra carefully. Their son Parker was 7 at the time.

Parker Peirce: Probably the most inconvenient part about it is remembering to tell people that haven't been here before–

Ben Peirce, off mic: Yeah.

Parker Peirce: –‘Cause, like, it's not like– We're just kinda used to it. But, like, if I have friends over that haven't been over before, then I– then we have to, like, remember to tell them that they can't drink the water.

Hoplamazian, narrating: It’s been almost six years since the first pallet of water showed up in the Peirces' driveway. Parker is almost a high schooler now. And they still can’t drink the water from their faucets.

Ben Peirce: I really don't think that day that I realized that it was a life-changing event. [LAUGHS] You know? Like, I-I knew it was a big deal. Like, I, you, you knew that it was gonna change the house and the home value and, like, you had all the panic, but you didn't realize that, like, as of this date, your whole existence is gonna change.

[THEME MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: How did this happen? What led to that water delivery at the Peirces’ house? That’s what I’ve been trying to figure out for a few years now.

What I found is a story about people who get stuck in the middle of something that doesn’t feel right…

Michael Hickey: And I started thinkin’, “Why are all these people always sick? You know what–?” 'Cause in a smaller community like this, you know what the neighbor has for illnesses.

Hoplamazian, narrating: …Who have to find their own way through a maze of chemical companies, government regulations, and the limits of science.

Loreen Hackett: When there's no answers, you’re just like, “Oh, okay… Got, just got dealt a really bad hand,” ya know?

Mike Wimsatt: It's always a gray. And people hate gray, right? But the world of a scientist is a gray world.

Hoplamazian, narrating: It's a story about the water in your faucet and the beginning of a problem that could last forever.

From the Document team at New Hampshire Public Radio, I’m Mara Hoplamazian. This is Safe to Drink.

[THEME MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: It’s March 2016 – three years before Ben Peirce chased his water delivery driver down the street. And we’re one town over from where Ben’s family lives – in Merrimack.

Merrimack is like a lot of other places in southern New Hampshire. There are industrial buildings fanning out from the center of town and a main drag with a park, a library, a few places where you can get steak for dinner.

On this night, dozens of people are filing into a school gym, filling up the chairs that have been set up on a basketball court.

Town Moderator Lynn Christensen: I think we're semi-under control here. DES is here, as well as a number of the town… [FADES OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: State officials called this meeting. They had just announced that something had been detected in Merrimack’s drinking water. A chemical called P-F-O-A. Perfluorooctanoic acid. They knew people would have questions.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: I wasn’t in Merrimack that night. I didn’t even live in New Hampshire in 2016. But I’ve been watching the aftermath of this night unfold since I started working as a reporter here.

There’s a recording of the night on YouTube. The room has the atmosphere of a town meeting. It's an annual tradition in New Hampshire.

Christensen: I’m gonna remind you that just like at town meeting, we have Merrimack manners. You guys have always been good about this. I wanna remind you that we're still under those rules.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Town meetings can be kind of sleepy – a couple dozen dedicated citizens showing up to vote on how much to spend on the sewer system or whether to cut down and sell trees from a town-owned forest.

But on this night, the room is absolutely packed. People bring in extra chairs for the crowd, but there still aren’t enough. Eventually, the walls are lined with people standing. Everyone is looking around at each other, whispering to their neighbors. It seems tense.

NH DHS Commissioner Tom Burack: This is not a situation that any of us wanted, and I want to assure you that we here are as concerned about this as you are.

[OFFICIALS PRESENTING ON STAGE FADES UNDER NARRATION]

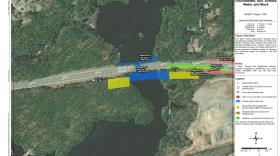

Hoplamazian, narrating: For an hour, state officials in suits give a presentation about this chemical that was found in the water – PFOA. A screen behind them ticks through slides full of acronyms, diagrams, color-coded maps.

They explain that this chemical is used to help manufacture Teflon products and that it’s part of a bigger family of chemicals… per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances. Nickname – PFAS. They don’t occur naturally. They’re manmade.

Dr. Ben Chan, on stage: [FADES UP] As, uh, Mike said, my name is Dr. Chan. I’m with the New Hampshire Division of Public Health Services… [FADES UNDER]

Hoplamazian, narrating: New Hampshire’s state epidemiologist, Ben Chan, tells the crowd these chemicals are in stuff we use all the time… microwave popcorn bags, fast food wrappers, clothing.

He says basically everywhere scientists have looked, they’ve found these man-made chemicals in the environment. But officials say the levels in the water in Merrimack are higher than the background levels.

Even though PFOA is everywhere… it doesn’t really seem like anyone knows very much about it. Chan calls it an “emerging contaminant.”

Chan, on stage: So, the big question here is what does finding PFOA in the water mean for our health, your health, the health of your loved ones? Uh… The, the, the quick answer is that the long-term health effects, uh, are really unclear.

Hoplamazian, narrating: “The long-term health effects are really unclear,” he says. Researchers are still studying them. There’s a list of potential health effects in really small type up on the big screen.

Chan, on stage: [FADES UP] …uh, to show you the types of health effects that are being studied… [FADES UNDER]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Liver enzyme levels, total cholesterol, uric acid, sex hormones, thyroid hormones, immune function, obesity, birth weight, kidney function, diabetes… cancers.

Chan, on stage: [FADES UP] …uh, kidney cancer, prostate cancer… [FADES OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: But Chan says the studies aren’t all coming to the same conclusions. They’re difficult to interpret.

Chan, on stage: [FADES UP] …What do these ultimately mean for a person's health? And the answer is we still don't know. Um, as an example… [FADES OUT]

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: And here’s where things seem to get even more confusing. The officials tell the crowd… they don’t really know what levels of this chemical are safe to drink. But they’re also saying… for most people, including everyone on the public water system, there’s no reason to believe it’s unsafe to drink.

NH DES official Mike Wimsatt: This is why it's very uncomfortable for us being involved in this project, because we usually have a clearly articulated standard that's enforceable under the Safe Drinking Water Act that's been fully vetted by all the toxicologists and physicians to make sure that it's a safe and protective number. We don't have that right now. So, we're using the best information we have to make a decision in the interim here about who we're gonna provide bottled water to.

Hoplamazian, narrating: In 2016, federal regulators hadn’t set a legal limit for PFOA in drinking water. The officials say New Hampshire has set its own limit out of, quote, “an abundance of caution.” And people in Merrimack with taps testing higher than the state’s limit would start getting bottled water delivered to their houses.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Christensen: Bring the mic up so you don’t have to s–… [FADES DOWN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: After they finish their presentation, officials open the floor for questions. Everyone gets three minutes to speak.

Man: [FADES UP] Much better. Uh, so, my wife is currently pregnant. Are there any, uh, any extra precautions that she needs to be taking…? [FADES OUT]

Woman: [FADES UP]…and get into the ground system. For those of us who have gardens and are feeding our children from them, are the plants absorbing the PFOAs or do we know that?

Man: [FADES UP]…um, ya know, animals and stuff, fishing and everything else for – Are they safe to c–to consume… for hunters? [FADES OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: The meeting drags on into the night. And over and over again, the people up on stage don’t really have answers.

[MONTAGE OF OFFICIALS]

Official 1: We don't know exactly what that level is…

Official 1: We don't know what the levels of exposure that we’re seeing are…

Official 2: There's a lot we don't know yet. We’re still trying to put the pieces of this puzzle together…

Official 3: I don’t know what the levels in the pond are…

Official 4: We don’t know what that…

Official 2: I'm sorry. We're going to have a frustrating answer on that. We don't know. We only know what we know from the recent…

Woman, on mic: …And if we don't know, why are you not telling us that we shouldn't be drinking the water? Can I drink the water? Can my pregnant patients drink the water? [APPLAUSE, FADES OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: The question that sticks with me most from this meeting came from a woman who had lived in Merrimack for almost 30 years. She told the crowd her husband had recently died of prostate cancer.

Second woman, on mic: My husband was a big water drinker – tap water. He liked it room temperature. [PAUSES, VOICE BREAKS] And my concern is… I was the one that gave him that water to drink. I don't know if I killed my husband… and that's my feeling right now. I don’t know what to do about it now.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: The gym emptied out after almost four hours, but there seemed to still be more questions than answers. What was this chemical? How did it get into Merrimack’s water? What was it doing to people’s bodies? And… what next?

Second woman, on mic, tearfully: Something and somebody has to be responsible for this.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

[MIDROLL BREAK]

Hoplamazian, narrating: From the start, suspicion fell on a local factory owned by the Saint-Gobain Corporation.

It was actually this factory that first detected PFOA in the Merrimack water supply, when they tested their own taps. That water was coming from the town’s supply. So, when the company found PFOA in that water, they reported it to the state.

Saint-Gobain was familiar with PFOA. They used it at the factory. But in letters to town officials, Saint-Gobain said they believed other sources, like a local landfill, caused the contamination. The company was basically saying… sure, their tests found PFOA in the town’s water, but it wasn’t their fault.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Saint-Gobain is a massive French manufacturing company, one of the oldest companies in the world.

By the way, a lot of people who worked there call it “Sahnt-Gobahn.” I’m going to say “Saint-Gobain” since that’s how most people say it in Merrimack.

The Merrimack plant was huge and a pretty big employer in town, but to Saint-Gobain, it was a tiny star in a big, global constellation. There’s a very good chance you’ve ridden in a car with a Saint-Gobain windshield or been in a building with Saint-Gobain siding or roofing or insulation.

In Merrimack, they were making coated fabrics.

Coated fabrics. It doesn’t sound that exciting. But the stuff they were making, it was kind of amazing. Think of all the things that make a material useful – lightweight, resistant to fire and water and sun. These fabrics could do it all.

Workers at the plant made those coated fabrics and then turned them into stuff like grill sheets for fast food restaurants and super-durable suits for emergency responders.

Right before Saint-Gobain bought the factory, it was owned by a different company called Chemfab. The plant had a few minutes of fame after they made fabric for a huge dome that was built in London to celebrate the millennium.

Millennium Dome Promo clip, Woman with British accent: [MUSIC FADES UP]…The dome at Greenwich, the biggest dome in the world and the first wonder of the new millennium... [FADES OUT]

Laurene Allen: So, everybody was like, “Whoa!” You know, “Look at this, the Millennial Dome! This is really cool.”

Hoplamazian, narrating: This is Laurene Allen. Merrimack resident since 1985. I’m not sure what determines who becomes an activist – some drive for fairness or a special brand of persistence. But whatever that thing is, Laurene has it.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: For her, this all started on her couch. She was watching the local public TV station. They were broadcasting a meeting about the PFOA contamination. She remembers how state officials couldn’t – or maybe wouldn’t – answer most people’s questions.

Allen: I'm picking up this arrogant, a little mansplaining, a little… They were patronizing some of them and I know that. As a female in my generation, I know when somebody's saying, “There, there, dear. Don't worry about it. The men have this under control.” I recognize that feel and I, I immediately say, “Somethin's going on here. Something's going on here.”

Hoplamazian, narrating: Laurene felt unsettled. One of the things officials said was that these chemicals had been in use since the 1940s. She was like, “What do you mean we don’t know anything about them?”

So, she started spending her free time researching. By 2016, you could find a lot about PFOA with a Google search. There were health studies, news stories, lawsuits… Laurene began breaking a central rule of her sleep routine – no electronics upstairs. She started bringing her iPad to bed.

Allen: So, the more you're going down Alice in Wonderland’s crazy world at a late time at night when everybody else is sleeping and you're going, “Oh, my freaking word!” And you feel like you’re the only one who knows this… But somebody has to know it! But is anybody connecting all the dots?

Hoplamazian, narrating: Laurene’s a therapist – not a scientist. But she felt her brain begin to work like an encyclopedia, rattling off facts and acronyms that she didn’t even realize she’d learned. And she had a clear feeling – This stuff, PFOA, it really doesn’t seem like it’s safe to drink. So, why were officials saying it was fine?

[MUSIC OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Laurene and a few other Merrimack residents started hosting meetings about the water at the town library and sometimes at Laurene’s house.

Hoplamazian, narrating: One of the other people who showed up was Wendy Thomas.

Wendy Thomas: We live in New Hampshire. We've got mountains, we've got lakes. You know, our water is beautiful. Um, I never– It never occurred to me that our water would be contaminated. It just never occurred to me.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Wendy raised six kids in Merrimack. By 2016, she already had experience with local activism. She’d organized to stop a gas pipeline from coming through town. But she didn’t know anything about PFOA. That is, until she heard Laurene talk about it at one of those library meetings.

Thomas: Boy, she knows her stuff. And she just rattled off all of these acronyms and all of these facts. And I was… I was like, “Wow.”

Hoplamazian, narrating: She remembers coming home from one of those meetings and telling her husband, “We need to get our well tested.”

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Their house wasn’t on public water. Like about half of people in New Hampshire, Wendy’s family got their water from a private well on their property.

But getting tested was complicated. Wendy’s house was about three miles from Saint-Gobain’s Merrimack plant. The state was focusing their testing on wells within a mile and a half of the plant.

Wendy and Laurene were skeptical of that radius. To them, it seemed like the state was saying anyone further away doesn’t need to be concerned about this.

Thomas: Even my husband was like, “The state says it's safe. You know, we, we–” And I was like, “I don't care. We're testing our water.”

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Okay, let’s step back for a moment. Maybe you’ve heard the saying, “The dose makes the poison.”

Doses of PFOA are measured in parts per trillion. You’re gonna hear parts-per-trillion a lot in this podcast – sorry.

The comparison used most often is that one part per trillion is like a droplet in about 20 olympic-sized swimming pools. It’s like one second in 31,546 years. Tiny, right? But you know what they say about the little things.

Remember, at the time all this was going down in Merrimack, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency didn’t have official regulations or limits for how much PFOA could be in drinking water, but they did put out some guidance. It shifted around over the course of 2016 from 400 parts per trillion to 70 parts per trillion.

In Merrimack, Saint-Gobain’s PFOA testing on the town’s public water was coming back at about 30 parts per trillion. So, all good, right? But next door in Vermont, their standard was 20 parts per trillion. That was confusing.

Then, there’s the fact that PFOA bioaccumulates.

[MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: That means it builds up in your body over time if you keep ingesting it… like a bathtub with a clogged drain. With a steady drip, the tub eventually fills up. That’s part of how PFOA and the family of PFAS chemicals like it got their nickname, “forever chemicals.” They stick around in human bodies for a really long time.

So, it matters not just how much PFOA is in your water, but how long you’ve been drinking it. And before 2016, the EPA’s guidelines were only for short-term exposure – not for water you’d drink over the course of a lifetime.

[MUSIC UP]

Hoplamazian, narrating: For people not on the public water system in Merrimack, things were even more confusing. When the state started testing private wells within a mile of the Saint-Gobain plant, some of those levels were coming in much higher than the town – at 190, 360, 820 parts per trillion.

Saint-Gobain agreed to pay for bottled water or other solutions for houses that tested over the guidelines the EPA was using.

As for Wendy, her well tested at 40 parts per trillion. So, well under the EPA’s guidance of 70, but double Vermont’s limit of 20. Wendy told her kids not to use the taps. They started drinking bottled water and installed two kinds of filtration systems. All together, she was out more than $5,000.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Water contamination isn’t the kind of fiasco that happens all at once. Months went by. The state and Saint-Gobain were negotiating. Many families were living on bottled water.

Merrimack was trying to get the chemical out of its public water. As the town tried to figure out their treatment options, they shut down the public wells testing highest for PFOA and kept others testing at lower levels online. For everyone on the public system, the word was, it was still safe to drink.

It seemed like people started settling into loose camps. There were some who trusted the official word – said, “Hey, I’ve been drinking the water. I’m fine.”

The other camp – Laurene, Wendy, and their friends – said, “No. We need to do something.” They started showing up to local government meetings, trying to get people to take their concerns seriously.

Thomas: And it was mostly driven by women. There were some men in this initial advocacy group, but we were hysterical women. We were fearmongerers. We were, you know, going to drive down the property rates in, in Merrimack. We were going to, you know, force businesses out of Merrimack. You know, we had better shut up if we know what's good for us.

Hoplamazian, narrating: At one town council meeting, several councilors told Laurene’s group they shouldn’t say the town had contaminated water.

Allen: Old guy – [USES DEEPER VOICE] “Don't say the word 'contamination.' It's inflammatory language…!”

Thomas: And you better believe from then on, I only used the word “contamination” because that's what it was. It is contaminated.

Hoplamazian, narrating: Another council member basically said, “This isn’t an Erin Brockovich situation.”

Town Councilor, on mic: I continue to drink the water. My wife does. My daughter does. My dogs do. Okay?

Hoplamazian, narrating: Town councilors were worried about jumping to conclusions. They were worried about the town getting a reputation.

Town Councilor 2, on mic: The last thing I want to do is scare anybody and overreact to something we need to deal with, but not to the point where we're going to scare anybody.

[THEME MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: From where I sit… here in the future, there’s something eerie about looking back at this moment, this fight about the contamination – even the word “contamination” – in 2017. Eerie… because all of this had already happened before.

This unprecedented, emerging contamination… it had already played out in another community 100 miles away. Like two towns putting on the same theater production. The set looked a little different. The cast was local. But the script, the themes, the choreography… they were mostly the same.

The plays are so similar that in this other town, the person playing the role of Laurene, a-local-resident-turned-activist, is also named Loreen.

Loreen Hackett: I'm not an activist, but I was pissed off. I was beyond angry knowing that now this was done to us.

Hoplamazian, narrating: That’s next on Safe to Drink.

[THEME MUSIC UP AND OUT, CREDITS MUSIC IN]

Hoplamazian, narrating: Safe to Drink is reported by me, Mara Hoplamazian.

Additional reporting and production by Jason Moon.

Our editors are Daniela Allee and Katie Colaneri.

Editing help from our News Director Daniel Barrick, Rebecca Lavoie, Taylor Quimby, Elena Eberwein, and Lau Guzmán.

Fact-checking by Dania Suleman. Legal review by Jeremy Eggleton.

Jason Moon wrote all the music you hear in this podcast.

Photos by Raquel Zaldívar, which you can check out at our website, NHPR.org/SafeToDrink.

That site was designed by Sara Plourde. Nate Hegyi designed our logo.

Safe to Drink is a production of the Document team at New Hampshire Public Radio.

[CREDITS MUSIC UP AND OUT]