At a house in Stoddard, a Cushing and Sons truck mounted rig pounds a drill bit into bedrock 90 feet below.

“What we’re hearing now is a pneumatic hammer,” says Bart Cushing, who together with his brother runs this family owned well-drilling business, “That’s a flat-based bit with carbide buttons. And it’s literally pounding the rock.”

These artesian groundwater wells are the norm these days: something on the order of 95 percent of new wells are drilled into the bedrock.

And there’s a reason for that.

Related Infographic: What You Should Know About Arsenic In Well Water

Dug wells used to be widespread – think the kind of well Lassie used to rescue Timmy out of – but they were exposed to run-off and surface water, so if there’s any bacteria nearby the water is easily contaminated.

“A lot of the dug wells that we see at least in our parts of New Hampshire, they were literally getting swamp water,” explains Cushing, “Often times at the low point of the area usually down gradient of what’s now the septic system.”

On the surface there can be E. coli, nitrates, and other things that will make you very sick very quickly. So in general, wells now go deeper, where the water has been filtered by layers of dirt, sand and rock.

But by going deeper, wells pull up water that has been soaking in whatever bedrock happens to be below the drill, and when it comes up, it could be carrying some baggage: naturally occurring elements in the earth’s crust sometimes come along for the ride.

“Normally what we test for, basic test is iron, pH manganese, occasionally arsenic if it’s in the right area, occasionally radon,” says Cushing, who’s company also includes a water conditioning business, “If we were next to a toxic waste site I’d recommend what they call volatile organic… VOCs – we do see those.”

There can also be uranium, or petroleum contaminants. None of them are good for you, but arsenic and radon are the two most common.

Arsenic In the Water

A full suite of tests – to find out exactly what is in your water – would cost something like $300 to $500, depending on where the test is done. But the state lab has a “standard suite,” which includes arsenic, for a subsidized rate of $85.

While there are plenty of possible contaminants in the state – notably radon – there’s a big push underway in New Hampshire to make more homeowners aware of arsenic, which is colorless, odorless and tasteless in drinking water.

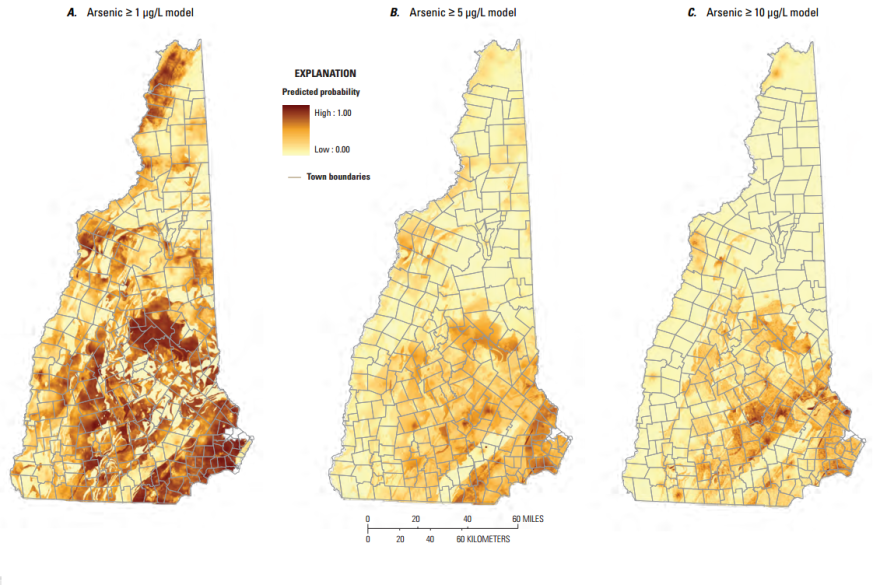

Dartmouth College just received a $13 million dollar grant to support its research into the health impacts of the chemical, and a US Geological Survey study released this week estimates nearly 50,000 people in Southeastern New Hampshire could be drinking elevated levels of arsenic.

But there’s plenty work yet to do in order to get the word out about the chemical to private well-owners.

The state lab does about 2,600 well water tests a year, but only around 38 percent of homeowners ask for the arsenic test. That’s only part of the picture: there are also numerous private labs offering similar services, which don’t have to report their figures.

So the question is: how many homes are getting tested?

Researchers at Dartmouth are trying to figure out just that.

“There’s no visual cue in their water, there’s no immediate health impact. So people may have lived with arsenic in their water for years and years and not had any problem,” says Mark Borsuk, who’s heading up the Dartmouth survey looking to determine how many people have tested their well for arsenic.

The last time this question was looked at was in 2003, when the USGS estimated that less than 14 percent of homes in Southeastern New Hampshire had had arsenic tests.

Compare that to Maine, where in 2004 26 percent had tested their wells, but after significant outreach by the state, that number was up to 42 percent in 2009.

Borsuk says there are basically three reasons people don’t test their wells: because they don’t know they should, because it’s annoying or impractical to do it, or – and this one is more insidious – because in the back of their minds, they don’t really want to know.

“If they’ve lived in a house for 30 or 40 years and have drunk water that may have had arsenic in it, they may be resistant to having the water tested because if they were to find it there may be a kind of guilt associated with having had that past exposure,” he explains.

Impacts to Body and Mind

Obviously, drinking arsenic at high levels isn’t good for you – it was after all, the poison of kings – but research has tied even low-level consumption over many years to issues like increased chances of lung, liver, skin, and bladder cancer and increased susceptibility to infections.

And then just this year, a study right here in New England found that children who drank water from wells containing even less arsenic than the limit imposed by environmental regulators did worse on an IQ test.

Joe Graziano, a Columbia University researcher who led that study, says kids scored somewhere around 5 or 6 points lower.

Which is not trivial, at all it’s somewhat comparable to low-level lead exposure, which we’re more familiar with,” says Graziano, “You know, on average, who wouldn’t want five more IQ points?

This study was pretty hard on some of those who took part.

One participant – who asked we not use his name for fear that his children would be stigmatized – learned that the well his family had used for nearly a decade had really high levels of arsenic: almost five times what the EPA says is safe.

“I mean it’s shocking information. Here you are you’re raising some kids, your making sure they’re in car seats, you’re buckling them up every day, you’re giving them good food, you think you’re doing everything you can,” he said in a phone interview, “And then you discover you’ve been feeding them poisonous water for ten years, and you can imagine how that makes you feel.”

Evolving Understanding

Arsenic concentrations are at their worst in the Southeastern corner of the state. That’s where USGS scientists estimate nearly 50,000 people could be drinking water with arsenic above the EPA limit.

It was in 2001, with mounting evidence that low levels of arsenic were unhealthy, that the EPA lowered its limit on arsenic in drinking water from 50 parts per billion down to 10. And it wasn’t until 2002 that the first study hinting that New Hampshire in particular had an arsenic problem was published.

The state really only started hustling to get the word out about arsenic in the last decade, but they have been trying.

“We don’t want to scare people, but we want to inform them, Arsenic is in our bedrock, it does get into your well water, you can’t determine by taste or odor or color, so the only way to find out is by testing,” says Cindy Klevens with the well water bureau at the state’s Department of Environmental Services.

The Dartmouth study seeking to determine how many people are testing and why others aren’t is due out in the fall.

But while arsenic in water may sound terrifying, it can be cleaned up. And solutions to arsenic in well water is what we’ll look at tomorrow.