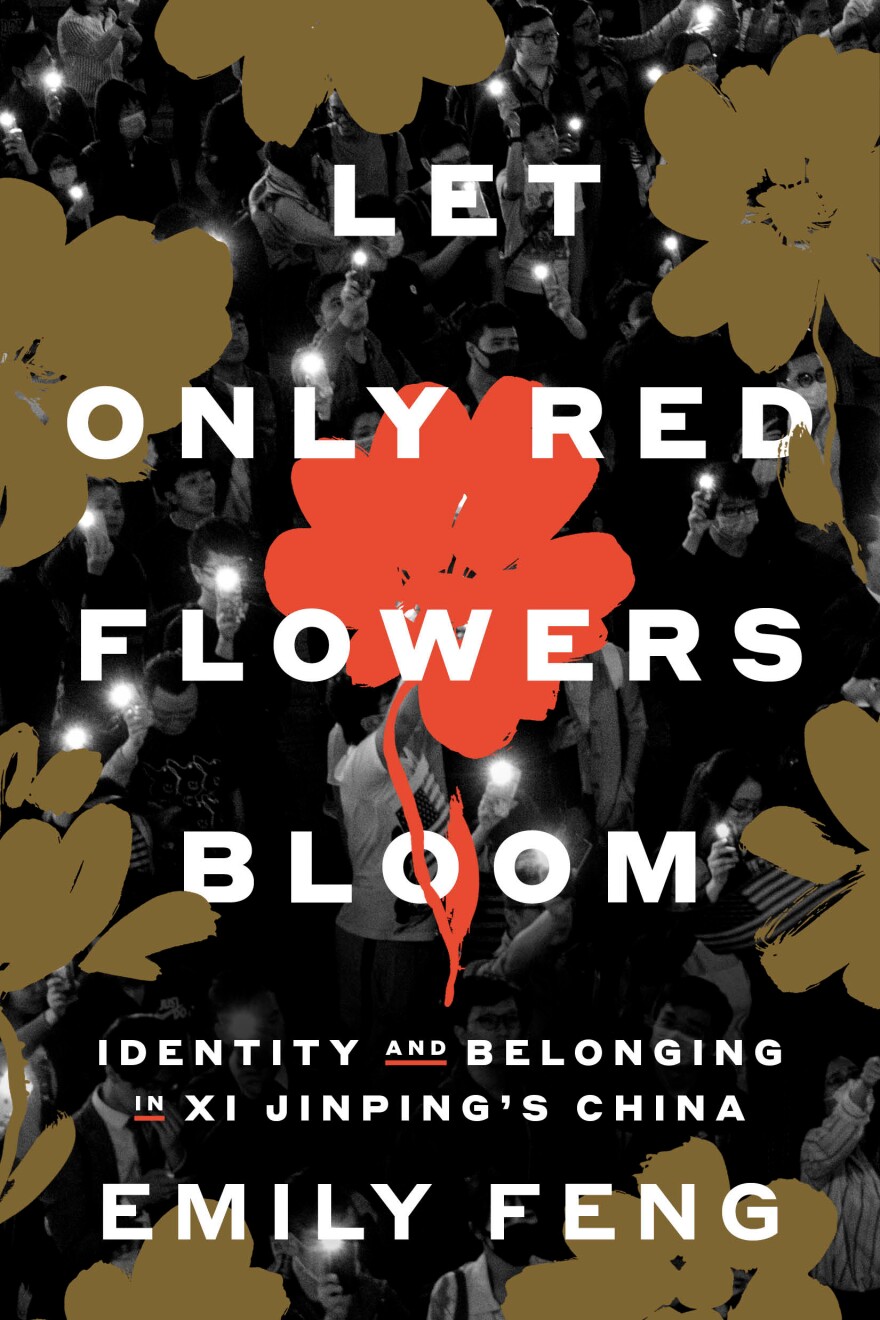

NPR foreign correspondent Emily Feng is out with a new book that recounts her experiences reporting on China during the era of Xi Jinping.

In "Let Only Red Flowers Bloom," Feng explores what it means to be Chinese as the country searches for its own identity. She joined NHPR’s All Things Considered host Julia Furukawa to talk about the new book.

Transcript

Emily, we as journalists talk to countless people, and you've been a foreign correspondent for years now. Each chapter of this book mostly focuses on one person. How did you decide which stories to share and narrow them down?

There was no scientific method. It was people who drew me in for whatever reason. About a third of the characters are people who I originally met because I was reporting NPR news stories, and I stayed in touch with them and their stories evolved, and I just kept being involved because I was interested. And the other two thirds were people who I either met or were, you know, peripheral to stories that I was pursuing for the news or had read about and put my journalist hat on and just kind of wrote a cold email to with no shame whatsoever. And as I kept reporting the stories, actually some of the characters started to overlap in their through lines. So, you know, people I would meet in mainland China would then show up in Hong Kong, and then people who I'd had met through my reporting in Hong Kong moved to Taiwan. And then people I met in Taiwan ended up connecting with diaspora groups that I was in touch with in North America.

So as the years evolved, the stories kept evolving and the characters kind of end up meeting each other in a way, which I think reflects the fact that China is a global story. You know, what we care about, what I follow isn't just confined within the borders of the People's Republic of China. But also these questions of identity, and China's soft power and, you know, cultural products being produced in the Mandarin language, that's not just happening in China these days. But every person who is in the book, I think, represents in some way through their life story, their lived experiences, some bigger aspect of Chinese politics, of a societal shift that I wanted to illustrate, but on a much more granular personal level.

Let's touch on one of the stories in your book. One that stood out to me was that of Yusuf, who converted to Islam and promoted the religion in his community in China. What does Yusef's story say about the diversity of the Chinese experience, religious or otherwise?

So yeah, Yusuf is one of tens of millions of Muslims in China. There are even more Christians, there's Taoists, there's Buddhists. You know, there's a huge plethora of organized and folk religions in China. So Yusuf is interesting to me because he writes so much and so prolifically as a Muslim scholar, and he has this religious epiphany in his teenage years as China is opening up, and he has kind of a born again moment for Islam. And he spends the rest of his life to this day trying to show how being Muslim is also inherently a Chinese exercise, and that the tenets of Islam are perfectly compatible, if not derived from traditional Chinese philosophies of Confucianism and Taoism and things like that. His viewpoints are actually quite controversial, even within China. But he's working explicitly with these ideas of identity and finds some space in China in the 90s and early 2000s to publish and write newspapers and start his own schools with his ideas. But as that space closes down, he and his family and his relatives come under a broader crackdown on religion and on ethnic minorities. And some of his relatives live in this western region of Xinjiang, where Chinese authorities have cracked down on another ethnic group called the Uyghurs. And although he is not Uyghur, he finds himself affected by the same policies. He now lives outside of China, and it's also one of the reasons why I use his Arabic name and not his Chinese pen name in the book.

Emily, you detail some pretty extreme cases of abuse against women in this book. There's trafficking. You share stories of medical abuse women endured under China's one-child policy. What was it like for you to report on and then write about these abuses as a woman yourself?

So I think that one of the things that I do is I detach when I work, and that helps a lot. But I wanted to write this particular story about someone who is now known as the chained woman in China, because I was detaching from this news story at the time, but I noticed it was affecting so many of my female Chinese friends at the time so viscerally. So what is the story of the chained woman? It was this TikTok video that surfaced during the Beijing Winter Olympics about three years ago, where a nameless woman was found chained by her neck in a shed in the middle of winter, and it unleashed this nationwide search for: Who was she? How did she end up under these conditions? To this day, and I detail kind of the obstruction that local authorities put up, we still don't know exactly who she is and how she ended up there. But people reacted so strongly because there is still such a problem with human trafficking and thorny issues of reproductive rights in China, not in the context that we know them, perhaps in the US, but because there had been so many controls under the one-child policy when families could only have one child, and that was often violently enforced in China. Now the limit is up to three. But it means that at various points, the state has tried to control how many children women have, and now they've flipped and are trying to encourage women to have as many children as possible when social mores have changed. People want smaller families now, and actually there's a lot of evidence that they even wanted smaller families when the one-child policy began. So through this story of the chained woman, I wanted to explore how gender is once again increasingly being defined by pro-natalist state policies. It's being defined in terms of reproduction. Whereas to China's credit, in the past, there was actually a lot of progress made on gender equality under the communists.

You cover some serious infringements on freedom of the press in this book, from local journalists being silenced, being banished, to your equipment being confiscated and searched. How does being a journalist in China differ from what your colleagues here in the States face?

There's so much gray space in China. So, you know, the rules are one thing. How they're implemented is another. It means that even sometimes when there are a lot of controls in place and digital surveillance, which became so pervasive in the last couple of years that I was reporting in China, there's still a lot of flexibility if you're a little bit daring and resourceful. And, you know, a lot of people are going to say no to you, but there's always going to be one person who wants to take your interview. It's actually really physically safe for female reporters to work in China. So although you and your sources might be tailed, I was never in danger of like, physical assault or anything like that. So I was just on the road all the time and tried to talk to as many people as possible and got a lot from that. But I think that a lot of what I learned in China, precautions I've taken with digital censorship and secure communications, I mean, in general, just kind of paranoia about the security of communications and protecting sources, attending protests and mass events like that, it's actually been incredibly useful for reporting in the U.S. And I think that, for better or worse, there have been more lessons that were applicable in China that I see my colleagues in the U.S. Now using.