Every other Friday, the Outside/In team answers a listener question about the natural world. This week’s question comes from Kathryn in Portland, Oregon.

“So we know that Seasonal Affective Disorder is a thing. But what if humans lived in an environment in the far north or far south where it’s dark for months at a time — do they experience health issues besides Seasonal Affective Disorder?”

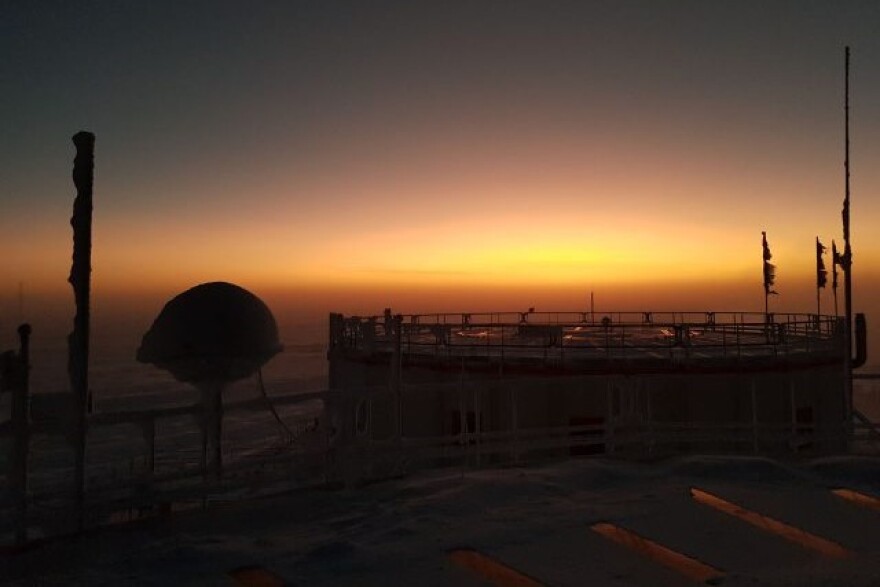

I leaned into the “far south” part of Kathryn’s question, and by that I mean the farthest south you can get — Antarctica. I called up researcher Carmen Possnig, who stayed a year at the Concordia Research Station, where the sun drops below the horizon from May to August. Possnig was studying the impacts of isolation, light deprivation and extreme temperatures on the human body and mind. She found that crew members’ heart rates, blood pressure and hormone levels for things like cortisol and melatonin were all disrupted — and their circadian rhythms were totally thrown out of whack.

“They couldn’t sleep at all at night,” Possnig said. “And I think it was extremely exhausting for [them] just to keep going through the winter.”

Possnig said people got depressed and easily aggravated at the station. Perhaps to make it more bearable, there’s an annual tradition there to celebrate a mid-winter festival on June 21, halfway through the dark period.

“Everybody is celebrating that from this moment on, in theory, the sun is coming closer again,” Possnig said.

She said everyone got a bit emotional the day the sun reappeared.

The caveat here is that they weren’t just dealing with light deprivation, they were also dealing with less oxygen (because of the high altitude of the Concordia Station) and the impacts of extreme isolation.

To get some insight on an environment that’s closer to what our listener Kathryn might experience in the Pacific Northwest, I spoke to clinical psychologist Kira Mauseth, who’s based in Seattle, Washington, and often treats people with Seasonal Affective Disorder, or SAD.

Mauseth said less sunlight means less Vitamin D, which is needed for a healthy immune system, and less serotonin, which is a neurotransmitter that’s good for your mood.

But according to Mauseth, SAD isn't just about a lack of sunlight.

“Things that are associated with sun around exercise, and getting out and moving…also have positive physical and mental health effects,” she said.

Many SAD symptoms come with simply being more sedentary and not going outside. Even the holidays, which can stress a lot of people out, can be part of the whole seasonal affective disorder malaise, according to Mauseth.

A common treatment for SAD are sun lamps, particularly ones with UVB bulbs. Mauseth said UVB light is what the body needs to make vitamin D, but cautioned that you may want to consult your doctor about any family risk factors related to skin cancer.

For those whose symptoms have more to do with the lack of exercise or getting outside than it does with the lack of sunlight, Mauseth said you should focus on behavioral changes like being active, increasing your connection with people and not isolating yourself.

Thankfully, the Outside/In team put together a list of 13 ideas on how to “surthrive” this winter that should help with just that. As for our experts, they’ve got their own ideas for how to befriend winter, too.

“Our family is a big snow family,” Mauseth said. “We ski, we're out in the woods in snow all the time.”

For Possnig, it’s all about that winter night sky: “You can go out at around noon, and you have the Milky Way, and galaxies, and nebulas, and auroras…. A lot of tiny suns.”

(For more details on the research Possnig did at the Concordia Research Station, as well as simply what life is like there, you can read Possnig’s blog)

Submit your question about the natural world to the Outside/In team. You can record it as a voice memo on your smartphone and send it to outsidein@nhpr.org or call the hotline, 1-844-GO-OTTER.

Outside/In is a podcast! Subscribe wherever you get yours.