A wastewater plant in Massachusetts says it will stop processing runoff from a landfill in New Hampshire because it contains high levels of PFAS chemicals.

But officials in New Hampshire say this local controversy is just one example of a widespread problem.

There are six lined landfills currently operating in the state – in Rochester, Berlin, Conway, Bethlehem, Lebanon and Nashua.

Last year, according to the state Department of Environmental Services, those facilities sent a collective 100 million gallons of runoff known as leachate for processing at nearby wastewater plants – mostly in New Hampshire.

DES spokesman Jim Martin says PFAS has been found in the leachate of all those landfills. But states, including New Hampshire, don't require wastewater plants to treat for PFAS.

It means the likely harmful industrial chemicals are still present in treated leachate that’s discharged from those plants into rivers that, downstream, are used to supply drinking water.

“This is essentially a problem that you could identify with any wastewater treatment plant across the country,” Martin says.

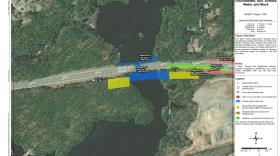

Concern for drinking water – and the cost of PFAS treatment - led the Lowell, Mass. wastewater plant on the Merrimack River to say this week it will stop accepting leachate from New Hampshire’s Turnkey Landfill in Rochester.

The Merrimack River supplies drinking water for several towns downstream of Lowell.

But the Environmental Protection Agency says its latest data, from tests done between 2013 and 2015, showed none of those towns’ water treatment facilities were taking in detectable levels of PFAS.

Martin, the DES spokesman, says this is likely due, in part, to the dilution of the contaminated leachate as it moves through the river.

In the next couple of years, New Hampshire will develop surface water PFAS limits that would affect wastewater plants. And the EPA says it’s studying potential future limits on the chemicals in industrial discharge – which would affect landfills – as part its broader PFAS action plan.

Meanwhile, public drinking water systems in New Hampshire are now required to test and treat for PFAS, under standards that are the strictest of their kind in the country. Water utilities’ first quarterly testing results are due by the end of this year.

Those standards also cover groundwater – meaning facilities like landfills must now monitor for PFAS in wells around their properties, too.

The latest state testing data shows wells at all six of New Hampshire’s lined landfills contained levels of PFAS that are considered unsafe under the new standards.

Martin, the DES spokesman, says landfill operators with elevated levels will be required to test neighboring private drinking water wells for PFAS, and may be held responsible for providing alternate sources of drinking water. They may also have to install treatment systems.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that one of the state's lined landfills was in Laconia. In fact, it is in Lebanon.