Over the last decade or so, scientists on Lake Champlain have noticed a concerning trend: Tiny pieces of plastic are everywhere.

Plastic has shown up in nets used for catching zooplankton, the tiny organisms that make up the foundation of the lake’s food web.

Plastic fibers have even been found in the guts of the zooplankton themselves — and even more concerningly, in at least 15 species of fish that eat them and that humans consume.

“Some 80% and upwards of the particulate we were finding were fibers like rayon, nylon-type stuff,” said Danielle Garneau, a professor at SUNY Plattsburgh who led these surveys and others looking at microplastics in wastewater. “You’d see these vibrant colors — fuchsia and blues and greens.”

But that’s not all: It’s also been found in wastewater effluent flowing from towns and cities along the lake, and most recently on beaches. But here’s the catch: scientists don’t really know where the plastic is coming from or how it could be affecting wildlife.

That’s why a team of researchers at the University of Vermont and Lake Champlain Sea Grant Program is combing Vermont beaches for trash this summer.

“A microplastic is anything smaller than the size of about a pencil eraser,” said Anne Jefferson, a researcher at the University of Vermont who is leading this work on beaches and rivers.

Jefferson said so far, her team is finding a lot of plastic from old toys and foam.

“Big plastics break apart and become small plastics and eventually microplastics,” Jefferson said. “So that single pool noodle could literally become millions of particles of microplastics.”

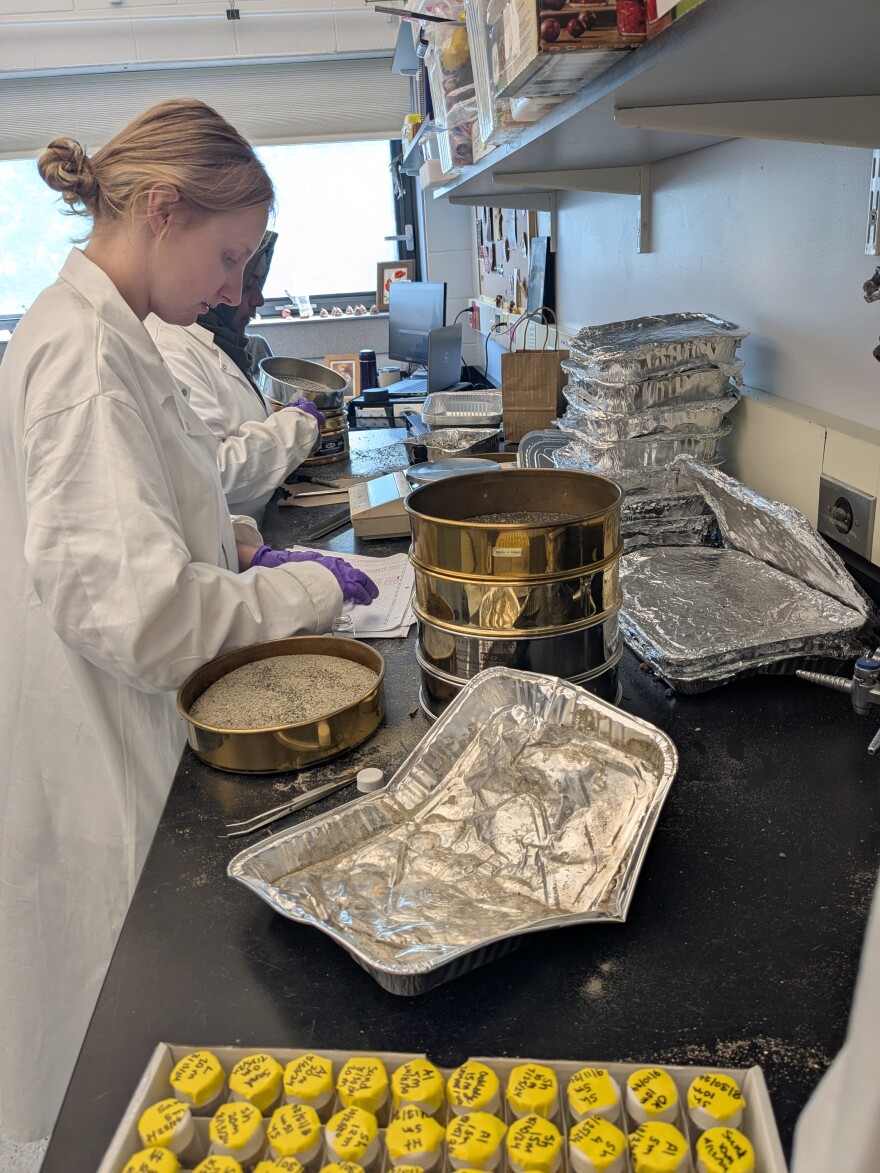

On a recent day at Burlington’s North Beach, Nurjahan Begum and Grace Massa were collecting sand samples along a measuring tape that ran from the waves to the boardwalk.

They scooped the sand into brownie tins to take back to the lab, where it gets washed with chemicals that dissolve the organic matter and leave just rocks and plastic.

From there, the scientists will examine the plastic under a microscope to identify it, potentially treating it with other chemicals to find out what sorts of compounds it might be carrying and leaching into the lake.

They’re looking in particular for tiny fibers, pellets used to make bigger plastic products and styrofoam beads. The hope is to figure out where it might be coming from.

“It’s just everywhere you look, once you start looking,” Jefferson said. “Our students find something on every transect on every beach — no matter how pristine it looks. We find plastic everywhere.”

Impacts to human health

Much has been written about the ubiquity of microplastics in the world’s oceans and in the Great Lakes, but it’s only been the last decade or so that scientists have looked more closely at the problem in Lake Champlain.

So far, they’ve found tiny beads of the sort used in face washes and toothpastes, but also fibers from clothing, bits of tires, foam and fragments from broken toys and goods.

And while their potential impact on fish and the environment is a concern, so too is their effect on human health. Microplastics get into the human body when we ingest them in food and drinking water. Emerging research suggests they’re in our house dust, too, as well as in the air pollution that comes from burning trash.

On top of that, some 200,000 people rely on Lake Champlain for drinking water, and most wastewater treatment facilities do not currently have filters installed that catch and remove microplastics.

There are many types of plastic, and a lot of them contain toxic chemicals. Instead of decomposing, they generally just break up into smaller and smaller pieces, and by that point they are difficult to remove from the environment.

There are some 16,000 chemicals that are added to plastics to give them their color and texture. Human exposure to them in the environment is only increasing, said Dr. Philip Landrigan, an environmental health researcher at Boston College and a pediatrician.

“Many of those chemicals are highly toxic,” Landrigan said. “Some are known causes of cancer. Others are toxic to the nervous system. Still others can disrupt endocrine signaling in the human body, which leads to decreases in fertility, birth defects in the reproductive organs.”

He said these tiny particles can move very quickly from the gastrointestinal tract into our bloodstream, and from there get into just about any organ in the human body.

Microplastics have been found in many organs in the human body, even in placentas. Just what these plastics do once they’re in the human body is an area of ongoing research — though they have been linked to a higher risk of heart attack and stroke. But it’s widely assumed that people who are pregnant as well as infants and children are especially vulnerable to their impacts.

How to protect yourself and the lake

When it comes to protecting yourself and Lake Champlain, scientists have some tips.

First, we need to stop microplastics from getting into the environment at all. That’s why research like what Danielle Garneau and Anne Jefferson are doing is so critical.

National policy is also critical: Garneau said she’s finding fewer plastic microbeads in the lake since those were banned federally from consumer goods in 2015 — a push she said started with local legislation in New York state. Vermont passed a similar law in 2015.

So too is global policy: 99% of plastic is derived from fossil fuels, and worldwide, we’re continuing to make more and more of it every year. That means more chemicals, and more microplastics.

And while taking steps to recycle is important, only about 8% of plastic globally actually gets repurposed. Avoiding purchasing plastic containers is even better. So too, say scientists, is requiring industry to do the same.

Dock foam is another big source of plastic in the lake, and Vermont lawmakers adopted a ban last year. Garneau hopes New York state will consider something similar.

Bans on single-use plastics like bags and styrofoam can also go a long way.

The recently founded Lake Champlain Basin Marine Debris Coalition hosts regular beach cleanups through the summer. Joining one of those can help remove plastics that ultimately break down and become microplastics.

Another huge step people can take is to try to avoid wearing and washing synthetic clothing, a potential source of plastic fibers in the lake.

Landrigan said you can lower your exposure by not microwaving plastic containers full of food, and by avoiding storing food or liquids in plastic in your home.

Lastly — drink tap water, and if you’re concerned about microplastics there, consider a filter. Either way, it’s almost certainly safer than drinking bottled water, Landrigan said.

This is the second year Jefferson’s team has sampled beaches along Lake Champlain, and Garneau will be leading research sampling at beaches on the New York side of the lake with SUNY Plattsburgh students this summer. It’ll likely take another full year to process all the data they’ve collected.

But at the end, Jefferson hopes they’ll know more about what kinds of plastic are washing up on the lakeshore and have better clues about where to look for its source.

“The key thing is that we need to stop the microplastics before they get into the environment,” Jefferson said. “And that means either dealing with the industrial sources or dealing with the macroplastics — the bigger things.”

Determining which microplastics are coming from where locally will be key to keeping them out of the lake.