Since last May, the Manchester Fire Department's Safe Station program has helped more than 1,000 people take the first step toward recovery from drug and alcohol abuse.

But while the first-of-its-kind program is being hailed as a lifesaver in the state's largest city, bringing Safe Station to other parts of the state may prove difficult: it requires treatment centers and other resources that most New Hampshire communities simply don’t have.

Last month during the season’s first snowstorm, I spent the day at Manchester’s Central Fire Station. Four people came in that day, looking for help for drug addiction.

One was a 61-year-old man from Bow - a painter who switched to heroin after using prescription painkillers for a bad back.

After a quick medical exam, he was escorted to a state-funded treatment center a block away by Manchester Fire Chief Dan Goonan.

“Have you ever been in treatment before,” Goonan asked.

“No,” the man replied as the two men trekked through the snow.

“How long have you been using?,” the chief asked.

“Three or four years," the man said. "I’ve tried before, I couldn’t do it. I just can’t do it on my own."

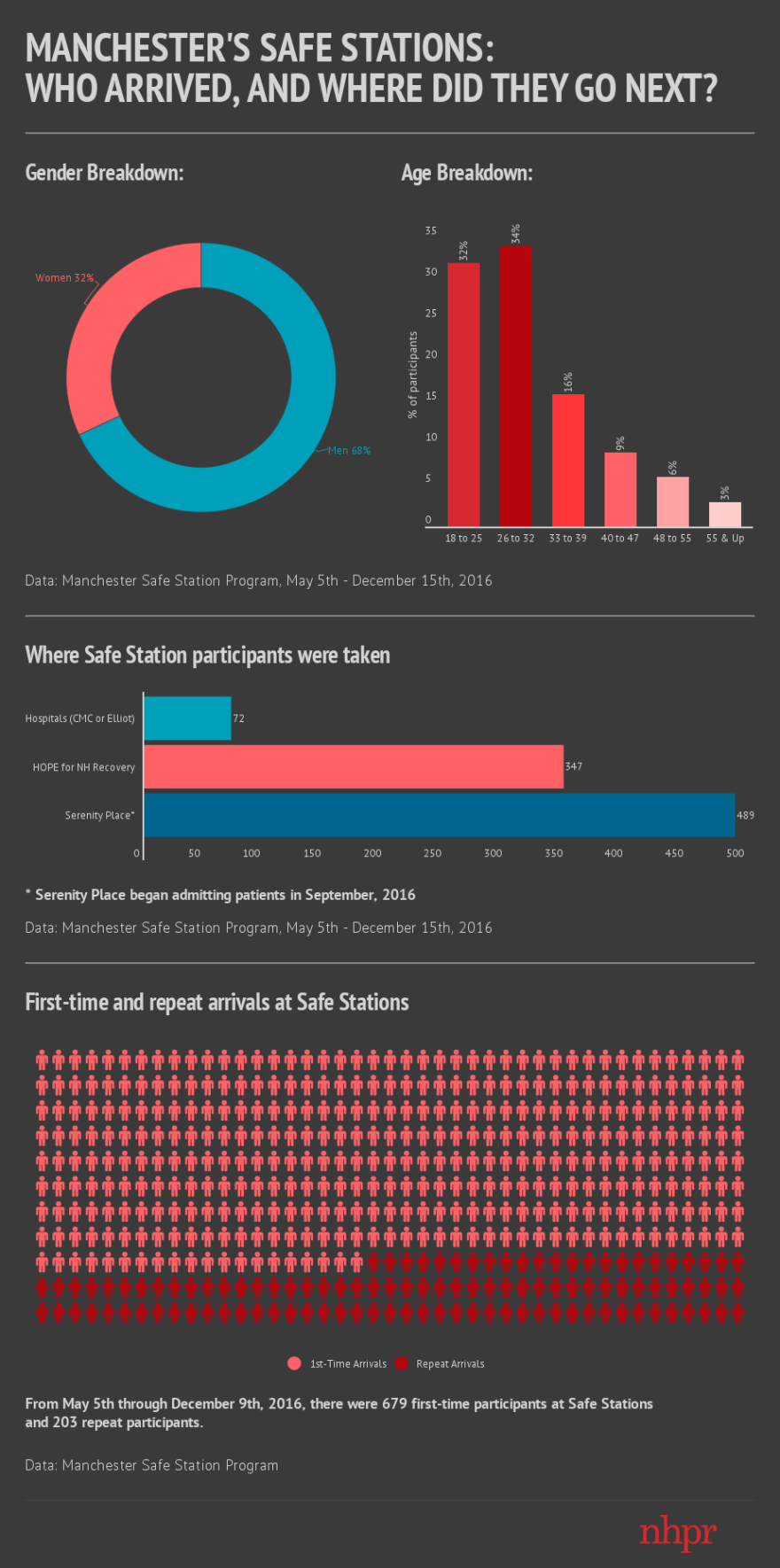

Map: Over 244 days, there were 912 arrivals at Manchester Safe Stations

Time of day key: Green: 7 AM to 3 PM Yellow: 3 PM to 11 PM Red: 11 PM to 7 AM

Safe Station arrivals from May 5th through December 15th, 2016 Data Source: Manchester Fire Department

Chris Hickey is the EMS Officer for the department and an architect of Safe Station. He said he got the idea after a relative of a co-worker walked into the central station looking for help with a heroin addiction. Three weeks later, the program had spread to all ten of the city’s fire stations.

“One of the driving forces for this program is the fact that people just didn’t have nowhere else to turn,” Hickey said. “Just because you’ve called and you have a spot in a program and you’re on a waiting list doesn’t mean oh magically you’re now sober. So we just wanted to make sure they had somewhere else to go to give them the encouragement to stay with it.”

Many who come through Safe Station have run out of options. Like 25-year-old Madisen Petersen of Farmington who walked into Manchester’s Central Station one day in October.

“You know I called around, and I didn’t have any insurance at the time because I lost my job, so I called around for different detox and there’s not much around New Hampshire right now for detox," Petersen said. "If there are, they’re full, so I couldn’t find anywhere to go.”

Firefighters took Petersen to Serenity Place, a short walk from Central Station. They found him a place to stay and enrolled him in the facility’s WRAP program, which tries to connect each client to the appropriate level of care.

Petersen, who said he’s been sober for three months, is now in an intensive outpatient program and volunteering part-time at Serenity Place.

While Safe Station receives no direct funding from the state, Serenity Place was awarded almost $2 million last year to get more people into treatment, from detox to long-term residential. There are still waiting lists for most levels of care throughout the state, said Executive Director Stephanie Bergeron. But no one who comes in through Safe Station is turned away.

“There’s a lot of tears in the morning and it’s usually of joy," Bergeron said. "Yeah, you had breakfast, you had a place to stay, and here you are doing 9 a.m. group, and you will meet with your case manager after and we will really make this happen.”

To keep up with the increased demand for treatment, Bergeron said Serenity Place has hired six new staff members and expects to hire more. Safe Station is still a work in progress, she said, but it’s already making a difference.

“We are at about a 60 percent success rate because we get about 30 people a month off to residential treatment," she said.

It’s too soon to say whether Safe Station will result in fewer overdoses in Manchester. From May 2016, when the program launched, through December, there were 509 overdoses and 49 deaths. That’s a slight drop from the same eight month period in 2015.

But Chief Dan Goonan said those numbers don’t tell the whole picture.

“I think this crisis would be worse if we didn’t have Safe Station, that’s how I justify it,” he said. “And we are seeing a dip, in three months’ time when you average, five people are alive now. How do you put a price on that?”

Despite its success, Safe Station may be tough to replicate in many New Hampshire communities. Fire stations have to be manned 24/7, and more importantly, there needs to be both a treatment center and an emergency shelter nearby.

Map: Where do people who went to Manchester's Safe Stations live?

Safe Station arrivals from May 5th through December 15th, 2016 Data Source: Manchester Fire Department

As the state’s "drug czar" James Vara explained to the state’s Executive Council in September:

“Manchester has available resources that a place like Concord just certainly wouldn’t have. So, you have to look at them and temper that with the fact that these approaches may not all work," Vara said. "Safe Station is a great access point for people who are suffering but they also have available resources like Serenity Place, which many of your districts wouldn’t have.”

Madisen Petersen says that if he hadn't made the hour and a half trip to Manchester, he might never have found treatment and be dead or in jail now.

“When I first came here I weighed 120 pounds, I was a bag of bones," he said. "And now I’m up to 160 now – I feel great. I can actually smile now and I love it."

Petersen says he wants to become a drug recovery coach. In five years, he’d like to have a home and a family. But for now, he says the greatest gift his recovery has given him is, “Seeing the smile on my mom’s face – she’s everything to me."

And, he says, you can’t put a price on that.