A group of New Hampshire lawmakers and scientists say manufacturing company Saint-Gobain might have misled state regulators about the quantity of PFAS chemicals used at their Merrimack facility.

In a series of letters sent to the New Hampshire Attorney General’s office throughout the month of July, the group highlighted public information from court cases in different states and in New Hampshire that suggest the company used more PFOA historically than state officials have previously understood.

“It wasn't clear to me, based on my work in commissions and things like that, that the state knew about these newly discovered facts," said Mindi Messmer, who founded New Hampshire Science and Public Health and signed all of the letters.

She says the letters are meant to provide background information to the Attorney General's office to use if they don't know about the facts already and “if it's relevant to understanding the full extent of the pollution.”

PFOA is one kind of PFAS chemical – a class of man-made chemicals that can be harmful to human health. Those chemicals were used widely in products like nonstick cookware, firefighting foam and waterproof clothing. They are sometimes called “forever chemicals,” because they break down very slowly.

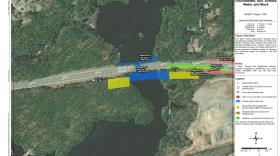

In 2016, Saint-Gobain notified New Hampshire that it had emitted toxic quantities of PFAS. The company is remediating some of that contamination within boundaries specified by a 2018 consent decree.

According to notes from a meeting of a commission to investigate environmental and health impacts of PFAS, about 650 properties sit outside of the area determined by the consent decree that are testing above state standards for PFAS. The state’s Department of Environmental Services says those properties are within “inferred areas of impact from Saint-Gobain’s releases.”

The department recently opened a PFAS removal rebate program open to people whose wells are testing too high for PFAS, but do not live in an area where a party has been deemed responsible for that contamination. Those rebates are funded by the State General Fund.

In the first letter to the Attorney General’s office from July 8, the lawmakers and scientists say the report that served as the basis for locating the boundaries of the consent decree did not include the historic use of pure PFOA and high-content PFOA, though court documents appear to show the company was using those substances in the early 2000s.

And, in testimony from 2022, Eric Edwalds, Saint-Gobain’s air emissions modeling consultant, said state regulators were in the same position as consultants: they did not know how historical emissions were affected by the concentrations of older materials. The letters also show New Hampshire’s Department of Environmental Services raised concerns about uncertainty in the models, including the use of raw materials before the early 2000s.

Messmer says the information could help determine if Saint-Gobain should be responsible for fixing contamination outside the current boundaries.

‘It's not right for public funds to be used to address contamination caused by an industrial pollution source like this,” she said.

The letters call on the Attorney General’s office to use the materials from court records to revise the boundary of the consent decree and hold Saint-Gobain accountable for “the full extent of their pollution.”

One letter also includes a fragment from a 2006 email exchange, showing the company discussed a program to test employees’ blood for PFOA that year. Messmer says having more information about the results of that program could help communities affected by contamination.

“That may help us understand what some of the people in that area – the citizens who were exposed to the air emissions – should be looking for,” she said.

In a statement, Saint-Gobain said the company denies any allegations of withholding data or misleading state regulators.

“Since self-reporting to the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services in 2016, Saint-Gobain has shared over 90,000 pages of documents with the agency, including purchase records regarding the products in question,” they said. A company spokesperson did not immediately answer follow-up questions about what “products in question” referred to.

The company also said it maintains an industrial hygiene program that offers medical exams and blood testing to employees, and that the results of those tests are protected health information that would not be shared.

Asked about the letters, the Attorney General’s office said they were reviewing the information.