I was in Mira HQ and all the lights were out. The reactor was failing. No one was doing any tasks because the doors were on the fritz and there were only three of us left: Brown, Pink and me. We ran in tiny circles in the dark, rotating around each other in small, panicked orbits, waiting to see who would make the final move ...

So have you played Among Us yet? Millions of you have. Millions of you sitting in dark rooms, on lazy afternoons, socially distanced, bored, frustrated, furious. It is a simple game that is deceptively complex. There are 10 players dressed as spacemen — colorful little sausages with funny hats and little pets — all running around a map, frantically trying to complete a bunch of make-work tasks. They're emptying trash and calibrating the engines, blasting asteroids (almost certain death, in my experience) and fixing the wiring. And all the while, one or two or three of their fellow space-sausages are secretly aliens. impostors, who live only to murder.

... There was one impostor left. Two crewmates. It was three in the morning, my time, and I should've been asleep but instead, I was staring at the screen, waiting, while the klaxons blared and the emergency lights flashed ...

You've heard of this game before, even if not in this format. The game — the basics of the game, its spine and format — has been around since 1986. Called Mafia (or Werewolf, depending on the particular flavor), it was a party game invented by Dimitry Davidoff, a psychology student at Moscow University, as a way to mess with a bunch of high school students he was tutoring. You take a bunch of players and have them draw cards. Most of them will be peaceful townsfolk, but a couple will secretly be members of the mafia who can kill other players every night. At night, everyone puts their heads down while the mafia decide who to murder. In daylight, everyone is heads-up and arguing over who they believe are the killers. The townsfolk win if they can correctly identify the mafia. The mafia win when they finally kill everyone else.

It is a deduction game, a psychology game. You read the room, ask your questions, make your accusations and see how each player reacts. Only a majority vote of players can indict a murderer and, at least in the early going, most of those votes are wrong. Among Us is the latest variant, launched to virtually no acclaim back in 2018 by an indie shop called InnerSloth with no particular talent for marketing, but a dogged determination to make this game work.

... 20 seconds left. Then 15. Someone was going to have to do something soon...

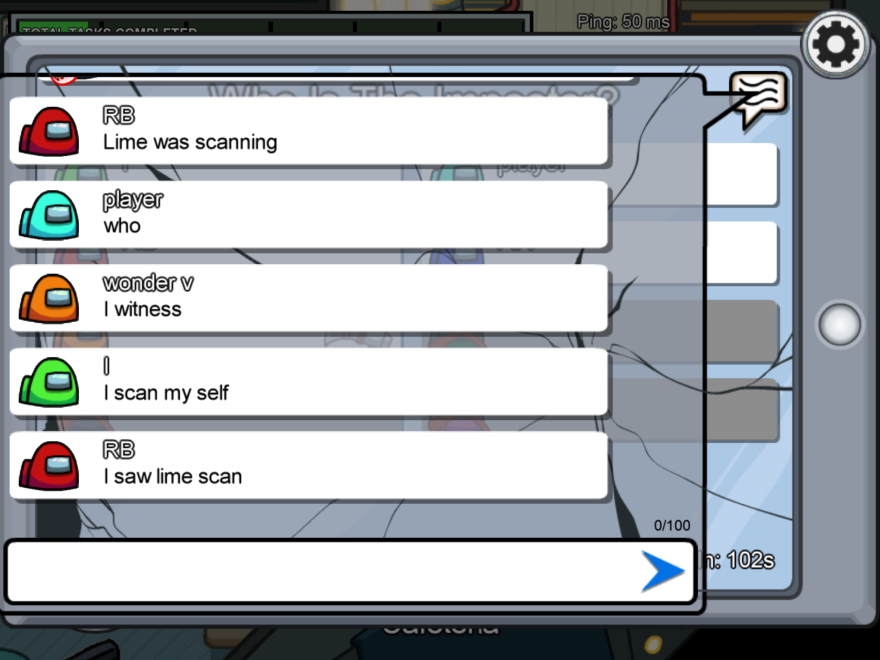

The mechanics are slight — you run around, do your tasks, try not to die. You stalk the players you think are suspicious, trying to stay in groups, in plain view. If you're an impostor, you try to look innocent until the moment you find yourself alone with another player. Then, you stabby-stab and run away. Impostors can use vents on the map to jump from one section to another. They can sabotage vital ship systems, sealing the doors, killing the lights, turning off the oxygen. As the game goes on, these sabotages stack up. In a good game, everything starts going wrong, and the bodies are everywhere. And the only time players are allowed to speak to each other — the only time they're able to point the finger and accuse someone of being an impostor — is during emergency meetings. Text chat is not a great vehicle for psychological subtlety. But it is all the little sausages have. And even within the limited framework of chat, there are tricks, gimmicks, ways to deflect and manipulate.

Most players don't do much but accuse ... The great ones roleplay. They overact like Brando chewing the scenery or act goofy or ally themselves with rando players, overwhelming the chat with detail.

Most players don't do much but accuse, shout "Sus!" over and over (meaning suspicious) or say some version of "No way, bro! Wuz w/blue the whole time!!" And that's fine. Sometimes that works. The good ones try to use math: Who was watching who, when, and who was unwatched long enough to do a murder? The great ones roleplay. They overact like Brando chewing the scenery or act goofy or ally themselves with rando players, overwhelming the chat with detail.

Not me, dud. Me an white an blue in lower engine watching red. He wuz gone for 2 secs, then meeting. Self report???

If you're a crewmate, you win by identifying all the impostors and blowing them out the airlock before the various sabotages and murderers end up killing everyone. If you're one of the impostors, you win when everyone else is dead. The voting can be cruel, capricious, reflexive. You're choosing based on faulty, incomplete data. There's an age-of-the-internet angle to it that makes people decide fast on the truth they want to believe and stick by it fiercely. That isn't always great for the game, but these days it seems ... apt.

...With 15 seconds before meltdown, Brown made a break for the reactor. Pink and I stood there, watching each other, waiting ...

Honestly, it kind of took the pandemic to make a game like Among Us work. It took Twitch streamers (first Korean, then Brazilian and Mexican long before it caught fire in the U.S.) screaming and plotting their way through games watched by tens of thousands of stuck-at-home kids (and parents). It took a wild night where Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez went on Twitter and asked if anyone wanted to play, then brought along Rep. Ilhan Omar and used the stream (watched by 439,000 people) to get out the vote. A game that, almost by definition, requires staring your opponents and fellows in the eye to decide who among them is lying seems a poor fit for small screens and fast fingers. And yet, there's something undeniably fun in the free-for-all of accusation and defense that happens in the chat. There's something weirdly engaging about the mechanics of the thing — the required tasks, the suspicious stalking, the little bits of help that exist for crewmates (like watching cams or tracking players on the map).

There's an age-of-the-internet angle to it that makes people decide fast on the truth they want to believe and stick by it fiercely. That isn't always great for the game, but these days it seems ... apt.

Yes, there are problems. Among Us is a game with its own quirky rhythms that you have to settle into. It takes time to learn the basics of movement and the mini-game tasks. (I can't tell you how long I stared at that stupid gas can in Supply, not able to figure out how to fill it, missing the giant button I had to push just to the right of the can.) You may have to go through a dozen failed games (ones that crash, ones that kick you out, ones that end suddenly for no good reason, ones where no one talks or where half the players leave before the first vote) before you find a good one with a good crew. Recently, there was a hacking problem that made the game essentially un-playable for a few days unless you were in a private game with a group of trusted friends, but that seems largely resolved.

Even with these issues, though, Among Us is still the ideal pandemic pastime. The stakes are low. The games are fast. They're frantic. They're a perfect bite-sized distraction from, well, everything, really.

... I could afford to wait. The lights, the sirens, they meant nothing to me. With just a few seconds left, I made my move. Killed Pink.

Game over.

The impostors win again.

Jason Sheehan knows stuff about food, video games, books and Starblazers. He is currently the restaurant critic at Philadelphia magazine, but when no one is looking, he spends his time writing books about giant robots and ray guns. Tales From the Radiation Age is his latest book.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.