The number of cyber attacks on municipalities is up from 2018, causing chaos and costing municipalities millions to resolve. We ask why local governments are being targeted, the impact on citizens, and the challenges for municipalities trying to protect themselves.

Air date: Thursday, September 19, 2019, at 9 a.m. and 7 p.m.

GUESTS:

- Denis Goulet - Commissioner of the N.H. Department of Information Technology.

- Margaret Byrnes - Executive Director of the New Hampshire Municipal Association.

Transcript:

This is a computer-generated transcript, and may contain errors.

Laura Knoy:

From New Hampshire Public Radio, I'm Laura Knoy and this is The Exchange.

Cyber attacks have hit more than 200 state and local governments in recent years. And those are just the ones that were reported. Municipalities especially are seen as soft targets by cyber criminals with a variety of technical and human vulnerabilities. And so local governments from Atlanta, Georgia and Rockport, Maine, have seen their computers hacked, critical systems held hostage and ransoms demanded today in exchange, municipal cyber security. Why these attacks are on the rise. Their impact and how hard it can be for states, cities and towns to protect themselves.

Our guests are Denis Goulet, commissioner of the New Hampshire Department of Information Technology and Commissioner Goulet. Nice to meet you. Thank you for being here.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Glad to be here, Laura.

Laura Knoy:

Also with us, Margaret Byrnes, executive director of the New Hampshire Municipal Association. And Margaret, a big welcome back. Thank you for your time. Good morning.

Margaret Byrnes:

Thank you.

Laura Knoy:

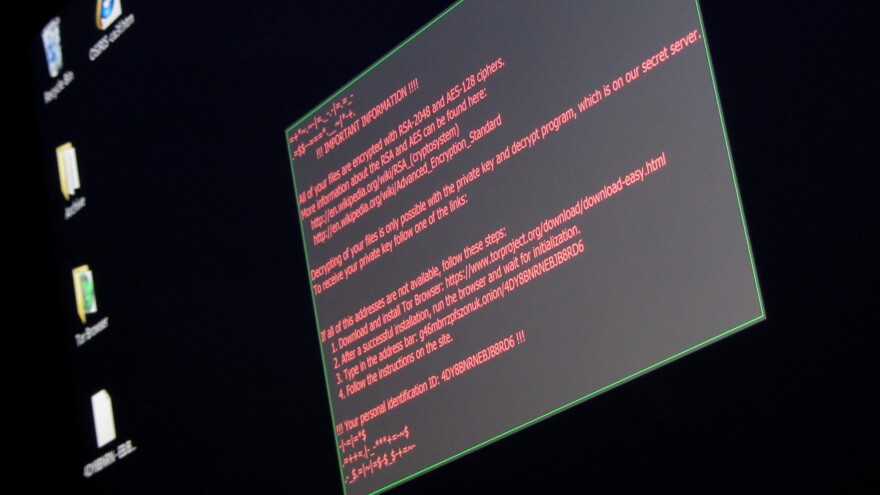

Well, Commissioner, according to The Washington Post, more than 200 state and local governments were hit by ransomware attacks in 2018 and 2019. What is ransomware?

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Well, there's two explanations. One is the technical one, which is really that that software that gets put on a computer actually encrypts all of the data. So it's inaccessible. The real definition, though, is making your systems not work as tools to hold them hostage for money.

Laura Knoy:

And so it locks everything up and it says will unlock it. State of New Hampshire once you give us X thousand million dollars.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Correct.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

And it's usually the the ransoms, usually in Bitcoin, which is pretty untraceable.

Laura Knoy:

Yeah. So what is the most dramatic example of this kind of attack that we've seen in the past year or two? Lots of headlines, unfortunately, around this.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Well, I've been exposed to a couple of them recently as as a member of the National Association of State CIOs. We peer in partner and help each other out across the country. A couple of big ones. Obviously, the the Baltimore example was hugely impactful to citizens because the city services were were rendered inaccessible. And you can imagine the NSA, a nine one one operator who's used to taking a call and knowing exactly where you are when that call comes in via a computer, going back to working on paper. So that's a really dramatic example of the impacts. And of course, all the communities in Texas at 26 of them all at one time.

Laura Knoy:

Wow.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Yes, that was very recent. And we heard from the the Todd Kimbriel well, the CIO of the state of Texas. And, you know, he was he he's unable actually to share a lot of the details because there's police investigations going on.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

So you have this duality where on the one hand, you really want to share information, help each other with police investigations, yet you have to be careful with that.

Laura Knoy:

Sure. And CIO is what?

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Commissioner, chief information officer,.

Laura Knoy:

What did your colleague in Maryland say that Baltimore example? I think it was last year was huge. What else did he or she say about just the impact on the city?

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Well, it had a huge operational impact because it took so many of the city computers down. And we do all our work now in government or almost all of it with computers. So that rendered it back to the old ill paper way. So slow downs, no access to information to provide human services, which we we do a lot of typically human services, a huge part of government. But for from his perspective, the governor said, hey, you need to get down there and help. But we're not geared you know, state governments aren't geared to do that kind of help. So there was that that challenge he was faced with from a resource perspective. So that that's really what's going on across the country now is is states and municipalities are struggling with that. Gee, we need help. But where's the resource to do that?

Laura Knoy:

Well, and I'm sure we'll talk about that as the hour rolls on. But Margaret, and many experts say these hackers see city and town governments as especially soft targets. Why is that?

Margaret Byrnes:

Well, it's an unfortunate designation to have, but I think it's certainly true. And probably the biggest reason why municipalities are seen as a soft or an easy target is that we all know the budgetary constraints that municipalities have.

Margaret Byrnes:

And so cybersecurity being up to date with technology, paying for really good third party services to provide that kind of services to the municipality. People know that they just don't have the budgetary constraints to be as up to date as they need to date to be, such as companies often are, you know, as big corporations. So they know they're a soft target. They know there are sort of easy ways in that they may not be as protected.

Margaret Byrnes:

And I think they're also an easy target because municipalities hold an incredible amount of information. And they also do an incredible amount of different things and provide an incredible amount of different services. So not only are they holding, you know, sense of. Personal data, but they also operate police department and libraries and provide welfare services and wastewater and and sewer and all of these other sort of services that if they get compromised, then municipalities are put in that position where they may actually need to make the decision to pay so that they aren't further compromised and that city services or town services aren't shut down.

Laura Knoy:

Wow. So you are really in a large pickle. If this happens.

Margaret Byrnes:

Absolutely.

Laura Knoy:

Describe if you could, please, and commissioner. You, too. But, Margaret, describe how much more connected local government is today than, say, 15 years ago and how that connectivity makes you more vulnerable.

Margaret Byrnes:

Absolutely. We all want to be connected because it makes things easier. I municipalities see being more connected, making their Web sites more interactive as a way to help the public interact with the municipality as a way to become more efficient from an intern internal perspective. And so that's a huge benefit. But the sort of inverse is true that it's also a huge burden because now they've opened themselves up to potential cybersecurity threats. And so if municipalities are sort of going ahead and getting more connected, they have to also go ahead and stay ahead of the cybersecurity threats. And that is going to be a cost.

Margaret Byrnes:

It's also going to be a time cost. They have to train their employees to know what to look out for. And so it's sort of a double edged sword. You know, it makes us more efficient to get, you know, to get connected. But we also have to stay ahead of the threats that come with it.

Laura Knoy:

Go ahead, Commissioner.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Well, in many cases, the municipalities are connected to the state network as well. And that's true in New Hampshire. So so if we find out that something happens to a connected entity, a town or city, we have to disconnect them very quickly because we're going to see that that risk can then proceed into the state network as well. So that, you know, that connectivity is in every state's different fact. The. The executive director for the National Association of State CIO is Doug Robinson, has has a quote he likes to say, as if you've seen one state, you've seen one state. But one thing that's pretty consistent is that there's this trend towards greater connectivity. The state government schools, sometimes even businesses and, of course, municipalities as well.

Laura Knoy:

Sure. Because of the tight fiscal relationship between cities and towns. It makes sense that there would be connections online. So you're saying, Commissioner, if you know town X, Y or Z ends up getting hacked. That's a vulnerability for the state.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Indeed, it could be. Yes. And we worry about that on two fronts. One is to catch it early so that we do disconnect and and we always offer assistance when that happens. Secondly, how do we know that? You know, once we've recovered, this municipality has says they're recovered. Have they actually. And so when you get a little nervous about reconnecting as well.

Laura Knoy:

All right. Describe if you could please, not just how much more connected government is, but how many more devices, Margaret are involved with that connectivity.

Laura Knoy:

You know, when we say computer systems, you might picture the person sitting at home in front of their laptop, but it's way more than that. The average person may have access to, you know, two or three or four devices.

Margaret Byrnes:

Absolutely. And so as municipalities have, many municipalities have sort of taken the route to go paperless and to digitize their records. And so they also have their employees being connected in different ways. So that paper isn't needed and that it's easier to communicate and connect. So you may see that all of your employees have municipal cell phone, maybe they have an iPad, they have a laptop, they have access to different systems within the municipality.

Margaret Byrnes:

They may remotely access systems, access systems within the municipality when they're at work. And so we have all of these different devices that are connected, but also all of these different humans that are connected. And I'm sure the commissioner will agree with me that cybersecurity is not just about, you know, the firewall and the updates in the most recent technology, but it's also about the human factor. And so you can give someone the most secure laptop and give them the best passwords ever. And if they still don't understand how to recognize phishing emails and they click on it, then that sort of all for not all of that, you know, beefed up security.

Margaret Byrnes:

So this huge human element and sort of one of the things that we've been, or I've been sort of thinking about, with the impact on municipalities and why they're such a soft target. There's this other piece of it, which is that a lot of municipal information is already public. So if I'm a person who wants to launch a phishing attack, I can actually find out easily what third parties they contract with, who are the people they normally communicate with? Who are they paying for services and really target them to make something look perfectly legitimate as a way to get into the system?

Laura Knoy:

Well, that's really interesting, because city and town governments need to be transparent for the public. You're kind of offering up half the information that an attacker might need. So thank you very much.

Margaret Byrnes:

Absolutely. And so I can go online and say, oh, the city of X contracts for this big service with this company. So if I sort of disguise myself that way, it could look legitimate and someone could fall for it and it wouldn't be unreasonable for someone to fall for it.

Laura Knoy:

Just remind us what a phishing attack is.

Margaret Byrnes:

So the commissioner can correct me and I hope he will if I get this wrong. But a phishing email is, you know, an email that you get. It asks you to do something to click on a link and it looks perfectly legitimate. So I'm your best friend and I am, you know, in Spain and I need 30000 dollars of bail money, you know? Can you help me out? But municipalities might get different things like, for example, you know, a contractor that they work with asking for a payment. And you click the link in you and you make a payment. And, you know, under those circumstances, the human factor comes in not only with recognizing phishing emails, but do you have internal processes so that those kind of things don't fall by the wayside. And it's not just sort of one person who clicks it and does something that can't be reversed.

Laura Knoy:

I'm glad you mentioned that because many reports on this issue talk about the human and technical weaknesses inherent in state and local governments. Commissioner, I'd like to hear from you, too, about the human side of this.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Well, Margaret's completely right. We see this these originally phishing attacks or these, you know, e-mail exploits have they've always targeted human factors, social engineering, they call it. And they started out being kind of broad. They'd send out a bunch of stuff and hope that a few people did at least seem pretty obvious.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

By the way, you know, someone who you know, maybe you knew, maybe you didn't with a introduction saying thought you'd like this, OK. I'm not going to click that.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Well, now we see ones that are specifically tailored to the individual. And I and we we limit, you know, everything about me. My public persona is available. So I could easily be easily targeted. And we actually see that a number of times where a great example is a run into, you know, a bad actor sends an e-mail to the payroll administrator and says, as the executive director or director or whatever, says, hey, can you please change my direct deposit account to this?

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

And so the payroll administrator and they found that information out on the state or city Web site, the payroll administrator goes, oh, you know, my boss just asked me to do this, so I'm going to run her quickly. Do it. And in markets completely. Right, you're having a process step in there that does has a double check because it's you know, that's a common exploit right now. Is the other redirecting checks.

Laura Knoy:

That seems like a pretty big ask to redirect to another financial account. If someone asked me that, I would want them to call me on the phone and say it in their own words.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

It works all the time, really, sadly, does it? It often doesn't work as well. In fact, there was a there was a very public one in New Hampshire a couple of years ago with our retirement system, where they sent out a press release saying that they had they had actually turned away one of those attacks. But it is a very common thing.

Laura Knoy:

Both of you talked about more connectivity with government and more devices, people working mobility, people working from home, people having laptops and work computers and so forth. Commissioner, you first. What about the so-called Internet of Things when it comes to governments being vulnerable? And also just please remind people what the Internet of Things is. It's a little different from your phone or your laptop.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

I'm glad you asked that, Laura, because it was rolling through my head as we were talking about this connectivity thing. More and more devices like if think about your home, right. You might have you know, you might say, Alexa, turn on my outside light. So that's Internet of Things.

Laura Knoy:

And what makes that turn on public radio?

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Correct. So we're seeing that in government like smart cities, for example, where the. There's all these Internet connected sensors throughout the city that are providing great services to citizens, but also those present of vulnerability, video cameras now are connected to the Internet. So the Internet of Things is, you know, we're gonna see smart cars, you know, with the 5G technology and smart cars coming and that'll be the Internet of Things on steroids. So the opportunity or what they call it's very technical term, but the attack surface, which is really how big the bad guys, how how big a surface the bad guys have to attack. That's growing with the growth of Internet of Things.

Laura Knoy:

Yeah. And actually attack surface is a perfect way to describe it because as more things are connected, makes things easier, quicker, but it also creates a larger surface for hackers. Can you also comment, Margaret, on the Internet of Things and how that may make local governments even more vulnerable?

Margaret Byrnes:

Well, I think that perhaps at least we are sort of all familiar with the traditional Internet and what the protections are. You know, that we know how to work our phone. We know we need to have a password. We have some familiarity as with, you know, updates and things along those lines, even if you're not an expert. But the Internet of Things is still relatively new to many of us. You know, we're still sort of getting more familiar with that aspect of it.

Margaret Byrnes:

So I would think that for municipalities, too, there could be even less knowledge about the implications of certain things. I with the example of video cameras, I think of police departments who are starting to go into the body cam world. So we have several municipalities across New Hampshire that have started to implement body cams for police officers. And that would be you know, there are so many things that come along with implementing something new like that. But then we have to think about the cyber security threat aspect of it to, you know, what happens if those get compromised or hacked. So there's just so much to it that municipalities, they want to move forward. They want to look modern. They want to provide better services to their citizens. But they do have to go slowly enough that they can consider the implications before they implement those new things.

Laura Knoy:

Our traffic lights, sort of coordinated traffic lights. Is that considered the Internet of Things? Margaret, traffic lights that don't you know that sense when you're there or when you're not there? So you're not sitting there at two o'clock in the morning and no one's around and you're still.

Margaret Byrnes:

I would think so.

Laura Knoy:

Go ahead, Commissioner.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

While broadly speaking, yes. It falls into really smart cities in that category.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

But then smart cities is a subset of the Internet of things and the use of connected devices to provide digital government services.

Laura Knoy:

All right. Coming up after a short break, we'll hear about how other cities around the country have been attacked.

Laura Knoy:

What the impact on their services were and the tough decision that they made as to whether to pay the ransom or not. We'll hear about two different experiences.

Laura Knoy:

This is The Exchange I'm Laura Knoy today. State and local cyber security with attacks on government computer systems on the rise. We're looking at their impact. The question of whether to pay ransom to these hackers and how states, cities and towns can better protect themselves. Our guests are Denis Goulet, commissioner of the New Hampshire Department of Information Technology, and Margaret Byrnes, executive director of the New Hampshire New Hampshire Municipal Association.

Laura Knoy:

And both of you. We've talked about how these attacks appear on the rise more than 200 in recent years. I want to bring the perspective of another city into our conversation. WBUR, our colleagues in Boston, produced a series earlier this summer called Hacked, where they interviewed two city managers who responded differently to ransomware. In this interview that we're going to hear in Lake City, Florida, manager Joe Helfenberger describes the attack on his city to WBUR viewers. PETER O'DOWD And we'll hear Mr. Helfenberger also explain why Lake City decided to pay the ransom.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

Cities are under attack. Big cities like Baltimore and Atlanta and small cities across Texas, California and Florida. They're falling victim to hackers who infiltrate computer networks, lock up data in key systems like email and phone lines, and then demand a ransom to get them back. By some estimates, city leaders in more than 60 cities have had to ask themselves an important question should we pay the ransom? We're going to hear now from two of those cities, each with a different answer. Joe Helfenberger is city manager at Lake City, Florida. They were attacked back in June. Joe, thanks for speaking with us.

Joe Helfenberger/WBUR:

Well, thank you for inviting me.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

And what happened when the hackers infiltrated your system that it just grind everything to a halt immediately?

Joe Helfenberger/WBUR:

It did. We came here on June 10th and there were no no use of the phones or the computer or anything that you normally communicate on. We had phone service restored about a day later, and this was the system, the non public safety system. The public safety system never missed a beat. So the cops weren't writing tickets by hand? No, they were not. But everything else was came to a screeching halt for a while.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

For how long?

Joe Helfenberger/WBUR:

The phone was down for one day. The use of the computers was about a couple of weeks.

Joe Helfenberger/WBUR:

We've got about 90, 95 percent unencrypted. We're still working on it.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

Okay. So the attackers demanded 42 bitcoins to release this data, which works out to about four hundred and sixty thousand dollars. Why did you decide to pay that?

Joe Helfenberger/WBUR:

I really had no other choice for a small city this size that has no financial resources to be able to respond. The cost to the city was the ten thousand dollar deductible. We had met the requirements for payments. We did our due diligence. We had tried to get the data restored unsuccessfully. We tried every other option. You're talking about utility maps and GSA data records for minutes and all the resolutions or ordinances, everything since the beginning of the city.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

Right. A lot of important information, but was there a debate inside the city about what to do? Because first of all, there was no guarantee that the hackers would release your files after you paid them all that money. And then, of course, the bigger picture is you might have encouraged them to hack other cities.

Joe Helfenberger/WBUR:

That is that is true. However, it's not our money to spend. It's the taxpayers money. You have to be extremely careful on your what you do. And this was a last resort option. We were not going to be able to recover the data. We were told by the vendors that with this type of attack, nobody had ever successfully decoded this military level of encryption.

Joe Helfenberger/WBUR:

And so we felt that the city would come to a screeching halt if we didn't, you know, recover this data. It would be a very expensive, very slow process to be able to recover the data. Any other option after we exhausted them, you said military level encryption.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

Do you know at all where this attack came from?

Joe Helfenberger/WBUR:

I don't know. We've left this in the hands of law enforcement to do the investigation. There's less sophisticated people out there in this cyber. Criminals seem to be able to increase their skill level constantly. So we have to go.

Joe Helfenberger/WBUR:

Going forward, we're looking at having enough protection and backup that we would be able to sustain an attack.

Joe Helfenberger/WBUR:

If we didn't that we'd have a recovery within 48 hours or so.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

Have you upgraded your systems and how much would that cost?

Joe Helfenberger/WBUR:

The upgrade to the systems right now is approximately three hundred thirty thousand dollars.

Joe Helfenberger/WBUR:

Yeah. I cloud storage or a backup solution for that multifaceted authentication and several other things. With all the upgrades that are being done, plus getting a high level of knowledge in the I.T. department within the city, that we will have a much better chance with the future.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

Joe Helfenberger City Manager. Lake City, Florida paid hackers a 460 thousand dollar ransom. Most of that covered by insurance to unlock the city's computer systems. Joe, thank you very much.

Joe Helfenberger/WBUR:

You're welcome.

Laura Knoy:

And again, that interview produced by our colleague at WBUR. Peter O'Dowd. Today, on The exchange, we are looking at municipal and state cybersecurity. The impact given that these attacks are on the rise. And Jeanne is calling in. Hi Jeanne. You're on the air. Welcome.

Caller:

I'm Senator Jeanne Dietsch and I wanted to say that I and Senator Morgan, along with some constituents, have been working on this issue.

Caller:

What I'm wondering is what you really need to protect our systems and particularly the upcoming election.

Caller:

Is it merely resources? Do you need legislation? What would be most helpful?

Laura Knoy:

Oh, Senator, I'm so glad you called. And we haven't even talked about election security yet. That's another vulnerability that I think we're going to do a whole separate show on that. But to both of you, perhaps you first, Commissioner Goulet, the senator is asking, what do you need to make this better?

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Well, it starts really with organizing around the problem. So do you think about it? One of the things we've been doing at the state, at the state level is is making it a whole trying to make a whole of state government approach. So each each entity, whether you're a state government or a city or a town or a county government, having the leadership of that government taking cybersecurity seriously. That's the start.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

And that's nothing technical about it. It's really because in the old days, businesses tended to look and say, hey, I.T., it's your job to protect me, but I can do anything I want in the network. And it's your job to protect me. That was clearly demonstrated recently that that doesn't work. And what we have to do is think together how we do this. Then that leads to organizing around it. And you have to choose a framework for doing it there. There are actually four major cybersecurity frameworks and you can the one that state and Hampshire uses is NIST Framework, actually, which is stands for the National Institute of Security Technology. And the in the in this framework provides guidelines for how you would approach doing this. And and then you look at that and say, OK, based on these guidelines, how well am I doing? We recently worked with the Department of Education to publish the minimum standards for data privacy in schools. And we used kind of a simplified approach for Nest on that. And we also have asked, you know, at the at the state government level, we have asked for appropriations and for the most part been granted them. So state New Hampshire has been very supportive of the needs of for cybersecurity for the state government.

Laura Knoy:

Well, Commissioner Goulet, we talked earlier about how cities and towns in particular are seen by hackers as attractive soft targets. What about state governments? Are they seen as less vulnerable than municipalities?

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Well, I think that state governments have been there a little ahead on the curve in terms of paying attention to this. So I've only been in state government for a little over four years. But right off the bat, I found that one of the major priorities for people in my job is cyber security. And if you look at how many attacks we turn away each day, which really can be in the millions on a given day, you understand why that's so important. So the National Association of State CIO is the chief information officers each year votes on has the CIO is vote on what their priority top 10 priorities. The last three years, cybersecurity been number one for four, the states. Go ahead, Margaret.

Margaret Byrnes:

To Senator Dietsch's question. And I know that Senator Dietsch has been very active not only in this area, but also sort of more broadly in New Hampshire's needs with regard to broadband, especially in the north country. But to her question, what do municipalities need? What do we need? And I think this goes directly to the commissioner's point. Municipalities are always more successful when there is state leadership and a state partnership, the state and the municipalities doing it together as a partnership. So that not only includes leadership that this issue is important and that the state cares about it and we're going to help you care about it and be successful in it. But it does also include resources and money so that their state buy in to say this is an important issue. We know it's expensive, but we want to help you succeed because then it helps the state succeed because municipalities are just subdivisions of the state. And so there has to be that level of partnership in that interconnectedness in order for there to be success in matters like this.

Laura Knoy:

Well, and it's interesting because the commissioner described earlier, if a small town is hacked, the state has to shut down its connection to that town. So there's really a strong linkage there. Yeah.

Margaret Byrnes:

Don't divide the issue. We're all sort of in this together. We're all learning it together. And the more that we put resources together, rather than sort of stand divided, the more likely we are to succeed.

Laura Knoy:

We played that interview earlier by Peter O'Dowd, at WBUR, talking to the Lake City, Florida manager who. Did decide, as we heard, to pay the ransom. He said, look, we just don't have any other choice. Our services were locked down. We're a small community. What did you make about that? That commissioner?

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Well, it brought back memories to me in the private sector all some years ago when ransomware first came to be. I was a victim of it. For one of the four, one of our software products that I was responsible for. And our company had a policy to not pay. And so we we were in that. What you heard last resort situation, and we knew we couldn't we couldn't pay. So we ended up recovering most of it. But that's not really an option for. For a lot of cities and towns, particularly if they don't have a good backup.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

The other thing I heard in that interview is that they're there, backups there, backups of their systems weren't recoverable. So it's one thing to back your systems up. That's really important. The second thing is you have to know that you can restore them. So testing, putting back that data is an important part of your backup strategy. And if you do that, well, that's a huge factor in being able to recover from one of these.

Laura Knoy:

Also in that interview, he said that really his only payout was the ten thousand dollar deductible from insurance. So, Margaret, are cities and towns now taking on ransomware insurance? I like disaster insurance.

Margaret Byrnes:

And I'm sure that some of our municipalities have I can't think of any specific examples that I know of of municipalities that have. But this is a new and real thing. Is this cyber security insurance, so that if there's an attack, they can pay the deductible in the same way that you pay a deductible if you get in an accident with your car and then they take care of the rest of the cost of that. And one of the sort of interesting aspects of cyber liability insurance and I sort of came up in the interview with the Lake City manager, is by having the insurance, are you making yourself a target? Because they know that you have someone who will pay and you are more likely to pay up because you do indeed have the insurance.

Margaret Byrnes:

And when it's 460000 ransom versus 10000 deductible than the city or the town is more likely to just make the payment. Of course, you want to protect yourself. But is there anything to be concerned about that you're making yourself more of a target by having insurance? Oh, my gosh, what a mess. It is a mass. And I I'm guessing and of course, I don't know this, but I'm guessing the recommendation is probably still to have insurance, that it's better to be insured in general as well as in this area and from a municipal perspective. It's not that you don't care what happens to other municipalities, but your primary objective is to get back online. And so if this is going to get you back online, then it's probably the better option.

Laura Knoy:

Good. Commissioner?

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Well, in the long run, depending on insurance isn't going to work because, you know, the rates now are set for cyber insurance. Well, actually, to me, lower than that than is sustainable. So over time, it's a pretty new product. They'll the companies will figure out where the guardrails are and the cost is either going to go up or they might decide, hey, you know, if you don't have a certain profile, I don't even want to insure you much like, say, if you're a really bad driver, you might have trouble getting car insurance.

Laura Knoy:

That's interesting. So cyber insurance, a relatively new product, something that state and local governments might decide to purchase to protect themselves against an attack. It sounds like you're saying, Commissioner, if that city or state goes to the cyber insurance company and says, hey, can you please cover me? That company may say, well, you know, your systems look pretty soft. So until you fix them, make them a little stronger, we're not going to bother you too much of a risk.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Correct. And that does happen today. There's a certain amount of information that you have to supply that help the companies set their rates.

Very interesting. Almost like health insurance, where if you smoke two packs of cigarettes a day, the insurance company is going to charge you more. Indeed. Very interesting. Talking about the insurance and the cost and how this emerging field of cyber insurance is sort of playing out. We also talked about the short term impacts on state or local government systems shutting down longer term impacts. Commissioner, you first, please. For example, can being the victim of a cyber attack lower your city's credit rating?

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

You know, I hadn't thought about that, but but I imagine if you. You know, the financial soundness of any organization will drive their bond ratings and bond ratings drive the interest you have to pay. So certainly the health of a municipality could be affected by that.

Laura Knoy:

Also, in terms of, Margaret, the way citizens feel about connecting with their city, about getting online, about getting information about, you know, the recycling more way store or snow closures, describe what may happen if cities and towns become increasingly vulnerable to that important communication that municipalities have with their citizens.

Margaret Byrnes:

Well, the ability to communicate via the Web site, via Twitter, via the Facebook page and other means that municipalities are using are hopefully helping citizens connect and engage with their municipality better and showing more transparency, helping people see what the city or the town is doing. And so as you build that up and get people more engaged, if that becomes compromised.

Margaret Byrnes:

If municipalities aren't able to use those means of communicating or allowing people to pay to register their car or pay their utility bill and be efficient in that way, then you are going to sort of lose the faith and support of your public, right where we're using the Internet and the connectivity to beef that up to get citizens engaged and see that their government is doing good things and that they can be part of the process. And if that just becomes increasingly compromised, if that's not working, then municipalities really backtrack and citizens really are affected by that in the long run. And so this is an unfortunate consequence. And again, it it goes back to the need for municipalities to if they're going to increase their connectivity, if they're going to increase their online services for better or for worse, they have to keep up with the updates and the security.

Laura Knoy:

All right. Well, coming up, we'll hear from another city that had a different response from Lake City, Florida, which did end up paying the ransom. We'll hear from Lodi, California, which decided not to pay the ransom.

Laura Knoy:

I'm Laura Knoy. Tonight at 9:00, a special broadcast to remember NPR's Cokie Roberts, who died this week. We'll bring you my 2008 interview with Cokie from our writers on a New England stage series. Join us for that special broadcast tonight at 9:00 this hour. Municipal cyber security. We're looking at the rise in ransomware attacks and how state, city and town governments are responding. Our guests are Denis Goulet, commissioner of the New Hampshire Department of Information Technology, and Margaret Byrnes, executive director of the New Hampshire Municipal Association. And both of you, we heard earlier from Lake City, Florida. They were hacked, hit by people who demanded a ransom. They decided to pay it because everything was locked out and they felt they had no other options. I want to play another interview from WBUR's feature called Hacked. Here's the response from Lodi, California, which was attacked a few months before Lake City. The city of Lodi did not pay the ransom. In this interview with WBUR's Peter O'Dowd, we're gonna hear from city manager Steve Schwabauer.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

And we're joined now by another city manager who dealt with the same problem but made a different decision. Steve Schwab, our is city manager in Lodi, California. That's in California's Central Valley. Steve, welcome. You just heard that conversation from Lake City, Florida. Did it feel like you were looking in a mirror?

Steve Schwabauer/WBUR:

Yeah, quite a bit. You know, we faced all those same decisions, all of our financial services, data, money that people owed us or utilities and money we owed our vendors for construction contracts and service contracts. Everything was locked up in terms of our ability to try to figure out who owed us money and who we owed money to. We still had phone service for our direct lines, but any kind of an extension would not work.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

Well, that's just that's just a nightmare for for a city. I mean, how do you even exist as a city trying to do the business of Lodi in conditions like that?

Steve Schwabauer/WBUR:

So, yeah, for our community. Very tough. We're all reliant on technology to give us the economies to make it possible to serve in a very complicated world.

Steve Schwabauer/WBUR:

And without it, it's very, very challenging.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

So speaking of looking in the mirror here, the attackers demanded about four hundred thousand dollars in Bitcoin. Sounds familiar, but you decided something very different not to pay that ransom.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

Why?

Steve Schwabauer/WBUR:

Well, it really comes down to the simple fact that it was possible for us to reconstruct our data. We would have had a much harder decision to make if our backup data had been compromised, but our backup data was not. In addition, we had several third party vendors who supplied our enterprise software who were able to set up offsite sites for us and allow us to operate from the cloud while we put together our onsite systems.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

If not for that, would you have had to pay?

Steve Schwabauer/WBUR:

You know, I hate to answer that question. I don't know what we would have done, but we would have had a very hard decision to make. I assure you.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

That is in. Is it because you were prepared for this, that you were in that situation? Did you put protections in place so that your backup files wouldn't be accessed by hackers in this way?

Steve Schwabauer/WBUR:

Perfectly. No better than some, perhaps. But, you know, it's always a difficult decision with a municipality. You know, we have limited budgets. We're not like the state of the federal government that can pretend we have money we don't have. We're constitutionally required to have a balanced budget. So we can't just go spend half a million dollars on I.T. protection system without cutting it from somewhere else in our budget. And so most cities in this country are facing that same challenge and they're having to decide, OK, now we realize how serious this threat is and we've got to start having a more robust I.T. infrastructure to prevent this from happening. Even Lodi has gone about spending about half a million dollars in buying additional resources to protect ourselves from future attack. And even that is ultimately no guarantee.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

And do you think that the hackers knew that that was your vulnerability, that you don't have the budget that the state of California does?

Steve Schwabauer/WBUR:

Well, you know, I think that they know that about municipalities in general. I I would be surprised if they knew the vulnerabilities of each particular city. As I understand the way they operate, they just send out broad fishing net rather than a single fishing line and they catch what they catch.

Peter O'Dowd/WBUR:

Let me just ask you a philosophical question. Why you think this is suddenly going on in so many cities like yours?

Steve Schwabauer/WBUR:

Well, I I think we have a very sophisticated group of threat actors. You see a crime of opportunity. And you're the victim. US, Sony. We've seen a lot of large technological companies get hit. It's anybody who is reliant on their I.T. infrastructure is a potential victim here. Just I think we're running through a cycle of municipalities.

Laura Knoy:

Again, that interview by public radio station WBUR's Peter O'Dowd. We are talking about municipal cybersecurity, state cyber security here in New Hampshire today on The exchange.

Laura Knoy:

So both of you. There is a city that decided not to pay the ransom. It sounds like they were in a better position than the Florida city that we heard from earlier, Lake City, that really felt like it had no other choice. Margaret, what did you think of that experience that we just heard about from Lodi, California?

Margaret Byrnes:

Two things. First of all, I thought his comment that they couldn't pretend they had more money than they had was so interesting. You know, the municipalities are under such scrutiny. Budgets are adopted, at least here in New Hampshire. Budgets are adopted annually. They only have as much money as they have in our towns. For the most part, in more than 200 of our municipalities in New Hampshire, town meeting adopts budgets and they make no decisions about how much to put in in different pots of money.

Margaret Byrnes:

And so they were really restricted by their financial resources.

Margaret Byrnes:

But the other thing I found very interesting and it made me think about this, you know, he said that they had the ability to not pay the ransom because their backups, they could access their backups. They knew they could access their backups even if it was going to take time to do so. They knew they could sort of get back there. And it made me think about what happens from a public perception. If your public finds out that you've managed your system so poorly that you cannot access your backups. So you have to pay five hundred thousand dollars in ransom. Now the public is looking at you thinking, why haven't you been managing your systems? Why did you just have to spend half a million dollars in taxpayer money to pay these criminals when the system should have been maintained the entire time? So if this happened, you could access your backup information.

Laura Knoy:

It's a two way street, though, because those taxpayers need to fund the cybersecurity, even though it's not as nice as having a brand new bridge or a brand new rec center.

Margaret Byrnes:

Hundred percent. You know, it's easier to sell. We're going to fix this road that you all drive down every day, and that makes people happy. They can see it, they can feel it. They see where that money is going. But, yes, the public needs to buy into the fact that municipalities need the funding and municipalities are holding all of our sensitive information, too. So we need to buy in to the need for those kind of systems.

Laura Knoy:

Wow. It's sounding more and more daunting the more I listen to you talk. Commissioner, what came up in that interview for you from Lodi, California?

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Well, two of the the big three things that you should be doing to protect yourself from ransomware attacks were where came in there. One that Margaret brought up was the backup and having the data accessible in an alternate way. The second was having an incident response capability. So it sounded like they they were able to kind of get their there, get organized around a response better than Lake City was able to.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

So those are the two of the big three for protecting yourself from from ransomware.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

But the third of the big three, which you're here might want to wonder, is not have it happened at all in the first place and that that's human factors, that's cyber awareness training. So if you're cyber right, where in his training is relatively inexpensive and if you're a municipality or any entity and you're not doing cyber awareness training for all of your employees and you don't have computer use policies that help instruct your employees on how they should and should not use their computers, then you have you're not doing something that has a huge impact. Can potentially another piece of awareness training is these these sending emails to employees that are done by I.T. or some outside company that's trying to get trained them not to click on the link. So most private sector entities, particularly large ones, now are doing this where they're they'll construct these really well-formed e-mails. They'll send them to employees trying to get either, you know, them to click on a link or give up their passwords. And as high as 30 percent when these programs start as high as 30 percent of employees do click on them.

Laura Knoy:

Wow. So to test their employees level of understanding about cyber threats. Commissioner, private companies are sending, you know, fake fake attacks almost to employees and seeing if they'll take the bait.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Correct. And so that that service is more expensive than cyber awareness training. So you kind of have two levels other. But they're both very helpful. But even the best that that in fact, I was just at a conference a couple weeks ago where it's a very large international companies were bringing their own statistics. The best was 4 percent. So they got it down to 4 percent. People clicking and if you think about it, how many people did it take to take down Baltimore? 1. So I lose sleep over this.

Laura Knoy:

I bet all the time. Well, and as we talk about vulnerability training for city and town employees, Margaret, cities and towns also use a lot of volunteers to carry out services to serve on boards and commissions. So what about those people?

Margaret Byrnes:

That is such a good question. And that is sort of as we started this show, we talked about what makes municipalities a soft target. And that would be another piece of it, especially here. In New Hampshire, there are so many volunteers, I mean, even think of our boards of selectmen. They're not full time employees. These are people really donating their time to serve in elected positions and help run the town. And so this is another piece that they need to be part of the training. They need to be part of the acceptable use policy. You know, they need to to sign on to that and know what the rules are. And another piece of this and I don't know if the commissioner has any thoughts on this. I think another part is both for employees and elected officials and volunteers, only giving them access and rights to the parts of the municipal system that they really need access to. Because if you compromise someone who has access to the entire network or the entire system, the they're more likely the hackers are more likely to get in and do more damage. So really sort of creating walls so that not everybody can, you know, cause a damage to the whole system.

Laura Knoy:

In addition to employees and volunteers. Commissioner, state and local governments use a lot of contractors to carry out government functions. What about getting those folks up to speed?

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Well, the when when you're selecting a vendor, part of, you know, security and compliance has to be part of that. So. So in your contracts, who's in your request for proposals? You have to specify what you need. With respect to security and compliance and then select a supplier that's appropriate based on that. And the third part, which is really important and often neglected, is pay attention to them and make sure that they comply with their contractual terms, because it is true that oftentimes it's bad behavior by a contractor that causes the breach, not necessarily a state employee.

Laura Knoy:

We got an e-mail from Mike who says, to what extent are New Hampshire municipalities required to notify their citizens about cyber security incidents? Mike, thank you for the question, Margaret.

Margaret Byrnes:

I'm trying to think I know that there there is a statute in New Hampshire that deals with notification, and I can't think if it specifically covers municipalities or not.

Margaret Byrnes:

So I'm going to throw this one over to the commissioner, because I am wondering if the city of Concord were hacked. Would my data be vulnerable? That's a great question, Mike.

Laura Knoy:

Go ahead, Commissioner.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

It's a great question. And it's there's no simple answer to it. It really depends on the type of data and and the context. So when, for example, when when we have a cyber incident, part of part of who we involve as attorneys to help us sort out what our notification requirements are, and there's a certain as there's it can be quite complex.

Laura Knoy:

Oh, I see. If there's an active law enforcement investigation going on, you may not be able to notify people just for legal recourse for the attorneys.

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

We may need the attorneys to help us parse all the different laws, both state and local and federal. With respect to that data, and sometimes there's rules about how quickly you have to notify. But in the most case, there is a rule that exists that says you have to notify often there's more than one law that says you have to notify and passing the requirements for that and then acting appropriately is part of an incident response.

Laura Knoy:

Well, Mike, thank you for the question. And in terms of what happens in the future, as both of you, I'm sure know, Senator Hassan and a Republican Senator John Cornyn of Texas have co-sponsored legislation to increase resources for state and local governments to bolster their ability to fend off these attacks, ransomware.

Laura Knoy:

Margaret, if this bill passes, where do you think any additional money from the federal government would be well spent?

Margaret Byrnes:

Well, we'd like whenever, you know, there's money that comes in from the federal government or an outside source to the state. Our concern at the New Hampshire Municipal Association is that that money actually makes it to the municipal or the local level so that it is able to be spent where it is intended to be spent. And so if there are going to be additional resources to help municipalities, then providing that money in the form of grants, you know, to do a certain thing or provide a certain service on the municipal level, that's really the important thing that it gets down to the municipal level and it be, you know. But for the specific purpose of cybersecurity training, whatever that whatever the need is on the municipal level, sounds like the training is a big piece.

Laura Knoy:

And also, as we heard from Lodi, California, having that really great backup system which saved them.

Margaret Byrnes:

Absolutely. I had never sort of thought until recently that we all back things up. But do we know whether we can actually recover the information that we're backing up? And also, do we know how long it takes to recover it? Because backing up may only take five minutes a day, but if you're going to recover an entire system, how long are we talking to recover that information?

Laura Knoy:

Many experts say these ransomware attacks are actually under reported. The number that's usually given is that there've been more than 200 in recent years. But you can't get a precise figure because they are believed to be underreported probably more than we realize. What's your take on that? Why would they be underreported?

Commissioner Denis Goulet:

Well, what I've observed is that there's two factors. One is that people really don't want other people to know when they make is when they have a perceived mistake. It's really a human nature thing. Right. And the second is that that that desire to know for sure before you report anything sometimes takes over. And we fight constantly against that perception. All right. Both of you.

Laura Knoy:

We could've talked a lot more. Thank you very much for being here, Margaret. Good to see you. Thank you. Good to see you. Margaret Byrnes, executive director of the New Hampshire Municipal Association Commission. Well, it was good to meet you. Thank you for your time. It was great to meet you. And thanks for exposing this important topic. Denis Goulet is commissioner of the New Hampshire Department of Information Technology. Again, a reminder that tonight at 9:00 o'clock, we'll be playing a special broadcast to remember and HP NPR's Cokie Roberts, who died this week. We'll play back for you. Our 2008 interview with Cokie talking about her just released book, Ladies of Liberty. So join us for that special broadcast tonight at 9:00.