New Hampshire has just 29 charter schools, which is fewer than most states. Over the next five years, the state wants to nearly double the amount of charter schools with the help of new federal funding.

In August, the New Hampshire Department of Education was awarded $46 million over five years to create 20 new charter schools, seven replications of “high-quality” charter schools and five expansions.

The state says they’ll be focusing on “traditionally underserved students.”

Much of the funding is for one-time start-up costs like laptops, school supplies and textbooks, among other things.

On Friday, the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee will vote over whether to approve $10.1 million of those funds for the next two years, as well as two new positions at the Department of Education that will focus on charter schools.

What is a Charter School?

The first charter schools in New Hampshire opened in 2004 after the passage of a 1995 state law. Charter schools, unlike traditional public schools, are publicly funded, but privately operated. They can be started by anybody with an idea, which is then approved or rejected by the State Board of Education, the body that both oversees charter schools and allocates their state funding.

Charter schools typically get more state money per pupil than traditional public schools. According to the non-profit Reaching Higher, charter schools receive an additional $3,411 per student in state adequacy aid. N.H. charter schools, however, do not receive local property taxes, except in the case of particular services like special education.

Charter schools often have their own unique missions, which can range dramatically. New Hampshire is home to charter schools specialized in nature-based learning, the performing arts, and the Montessori method, among others. Advocates believe that charter schools can offer more options for students with specific needs, interests or learning styles.

Challenges of Building a School:

Spark Academy Charter School in Manchester was the only charter school to open in New Hampshire this year. The high school, which is located on the campus of Manchester Community College, focuses specifically on advanced manufacturing, with topics like robotics and computer science.

Denis Mailloux is one of the co-founders of Spark Academy. He and his staff spent the whole summer building this school — ordering supplies, attracting new students and developing the curriculum.

He says starting this school wouldn’t have been possible without the help of key support -- an education foundation provided startup funds and the community college plans to collaborate on academics and share equipment.

“This school by its very nature could not exist anywhere else,” said Mailloux “The technologies that are available to the school because we are here on this site are hugely expensive but very essential to this program.”

Even advocates agree that starting a charter school is often an uphill battle. Matt Southerton is the President of the NH Alliance for Public Charter Schools,a pro-charter school non-profit.

“Opening a charter school is not easy,” said Southerton. “Especially in New Hampshire, where frankly, we’re underfunded. It is very difficult. On average it takes one-to-two years to open a charter school.”

He thinks the new grant money will help charter schools grapple with the toughest challenges of starting a school, which are often: getting enough students, finding an affordable space and raising enough money.

Because charter schools don't receive much funding from local property taxes, outside fundraising can make or break a school.

“Fundraising is definitely a very important piece in at least charter schools in New Hampshire,” said Southerton. “I would say that probably on average they’re going to have to raise at least 20-30 percent of their funding from outside donations.”

After the charter is approved and a school opens, charter schools enter what some consider to be the three most difficult years.

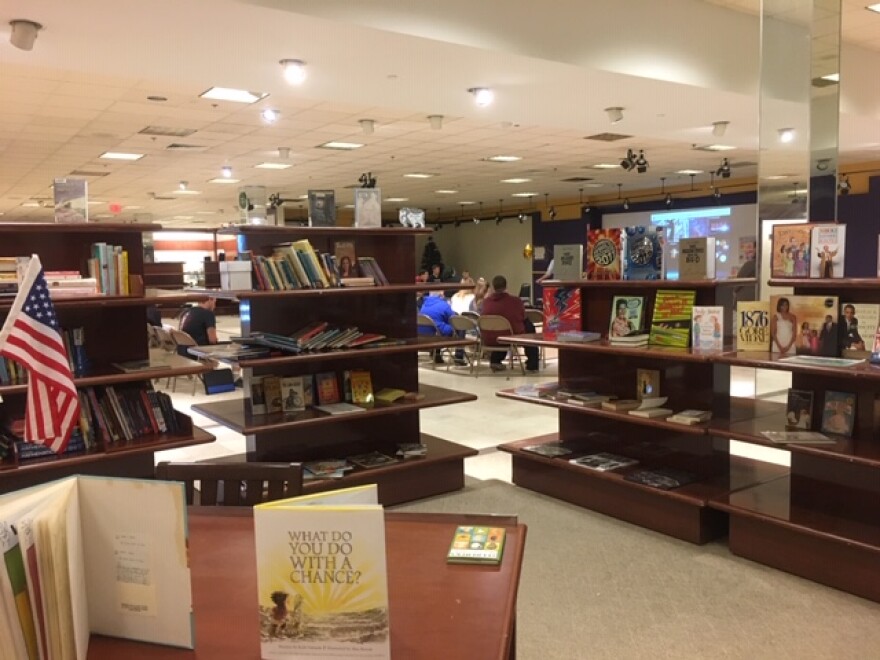

Capital City Charter School in Concord is also in that early trial stage. The middle/high school, which focuses on service learning, opened its doors in 2018. Right now, the school is leasing space out of the Steeplegate Mall.

The space was formerly occupied by a Bon-Ton Department Store. School leaders say it was difficult to find a big enough facility that also abided by school building requirements.

The staff has made the most out of the situation - by converting old display racks into library bookshelves and a former dressing room into a quiet room for students.

“You know we have lots of space that’s fluid and moveable and writeable and fun, I hope,” said Stephanie Alicea, the Principal of Capital City Charter.

Similar to Capital City Charter, a 2018 analysis showed that most charter schools in New Hampshire rent space from for-profit organizations.

“Space at a price you can afford...it’s not easy,” said Southerton. “You can see the disparity.”

The state’s hope is that the new federal grant will lighten these loads, by sharing best practices, providing more support and startup funds.

The Grant Sparks Concerns

The state’s effort to rapidly expand charter schools does have some critics nervous.

Representative Mary Heath is a Democrat in the House, who used to work in the Department of Education. She is concerned that this expansion might negatively impact traditional public schools in the state that are already struggling.

“20 additional charters is a lot for the state of New Hampshire -- we’re a small state,” said Heath. “On top of that, our enrollment across the state has been declining. We have very few public schools now that have increasing enrollment.”

Some lawmakers, particularly those concerned with protecting public education in New Hampshire, are likely to scrutinize the state’s plan. They’re worried about how the state and local taxpayers will pay for the new schools, especially when federal money dries up in five years.

Others doubt that the state can meet its stated goal of serving educationally disadvantaged students.

But Drew Cline, chair of the State Board of Education, has faith in the project. He believes the federal grant has the capacity to make charter schools better, by providing more support to charter schools from the state.

Cline also sees new improvements to the oversight process coming soon. He says the State Board of Education is planning to amend some of the rules for existing and new charters.

“We’re going back and taking a look at those rules and seeing how the rules can be more accommodating, while also holding charter schools more accountable,” said Cline. “So it’s a process we’ve already started. We don’t have any outcomes yet.”

If lawmakers approve the funds on Friday, the grant will then move to the Executive Council for approval.

MAP: Explore our map of current, former, and future charter schools in New Hampshire. (Note: The Virtual Learning Academy Charter School - or VLACS - is not included on this map as it is an online school)